By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

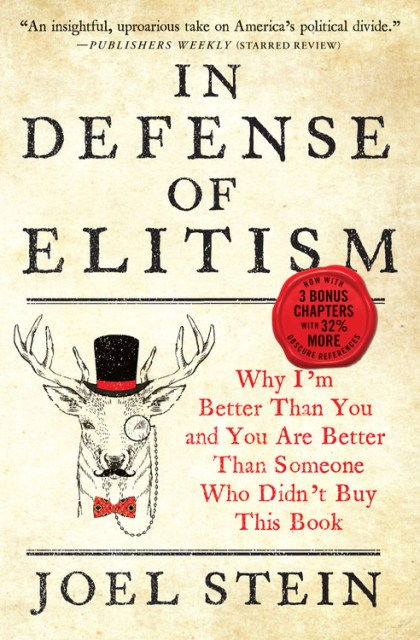

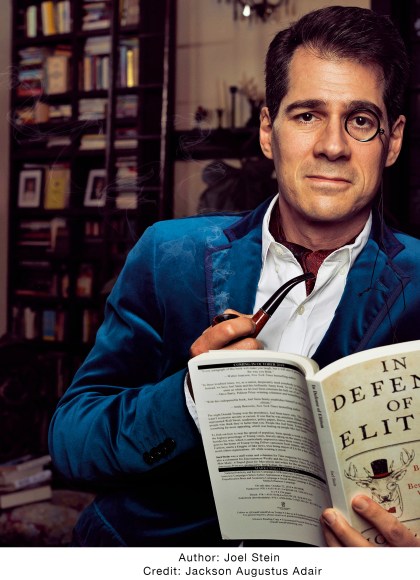

In Defense of Elitism

Why I'm Better Than You and You Are Better Than Someone Who Didn't Buy This Book

Contributors

By Joel Stein

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 13, 2021

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455591459

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 13, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Experience a “brilliant exploration” (Walter Isaacson) of America’s political culture war and a hilarious call to arms for the elite, with three chapters on foibles of the pandemic era.

“I can think of no one more suited to defend elitism than Stein, a funny man with hands as delicate as a baby full of soft-boiled eggs.” —Jimmy Kimmel, host of Jimmy Kimmel Live!

The night Donald Trump won the presidency, our author Joel Stein, Thurber Prize finalist and former staff writer for Time Magazine, instantly knew why. The main reason wasn’t economic anxiety or racism. It was that he was anti-elitist. Hillary Clinton represented Wall Street, academics, policy papers, Davos, international treaties and the people who think they’re better than you. People like Joel Stein. Trump represented something far more appealing, which was beating up people like Joel Stein.

In a full-throated defense of academia, the mainstream press, medium-rare steak, and civility, Joel Stein fights against populism. He fears a new tribal elite is coming to replace him, one that will fend off expertise of all kinds and send the country hurtling backward to a time of wars, economic stagnation and the well-done steaks doused with ketchup that Trump eats.

To find out how this shift happened and what can be done, Stein spends a week in Roberts County, Texas, which had the highest percentage of Trump voters in the country. He goes to the home of Trump-loving Dilbert cartoonist Scott Adams; meets people who create fake news; and finds the new elitist organizations merging both right and left to fight the populists. All the while using the biggest words he knows.

“I can think of no one more suited to defend elitism than Stein, a funny man with hands as delicate as a baby full of soft-boiled eggs.” —Jimmy Kimmel, host of Jimmy Kimmel Live!

The night Donald Trump won the presidency, our author Joel Stein, Thurber Prize finalist and former staff writer for Time Magazine, instantly knew why. The main reason wasn’t economic anxiety or racism. It was that he was anti-elitist. Hillary Clinton represented Wall Street, academics, policy papers, Davos, international treaties and the people who think they’re better than you. People like Joel Stein. Trump represented something far more appealing, which was beating up people like Joel Stein.

In a full-throated defense of academia, the mainstream press, medium-rare steak, and civility, Joel Stein fights against populism. He fears a new tribal elite is coming to replace him, one that will fend off expertise of all kinds and send the country hurtling backward to a time of wars, economic stagnation and the well-done steaks doused with ketchup that Trump eats.

To find out how this shift happened and what can be done, Stein spends a week in Roberts County, Texas, which had the highest percentage of Trump voters in the country. He goes to the home of Trump-loving Dilbert cartoonist Scott Adams; meets people who create fake news; and finds the new elitist organizations merging both right and left to fight the populists. All the while using the biggest words he knows.

-

"With this indispensable book, Joel Stein firmly establishes himself as the Ted Nugent of elitism."--Andy Borowitz, New York Times bestselling author and writer of The Borowitz Report

-

"Every paragraph of this book will make you laugh, but it will also (I promise) change the way you think. Joel has written a brilliant exploration of the supposed divide between elites and populists, cleverly disguised as a humorous personal excursion. Like Don Quixote he forays into perilous territory, his lance at his side, and what he finds will surprise you. Deeply reported and poignant, with a light touch of sweet self-awareness, his journey can help us all take our minds to a better place."--Walter Isaacson, the New York Times bestselling author of Leonardo Da Vinci and Steve Jobs

-

"I can think of no one more suited to defend elitism than Stein, a funny man with hands as delicate as a baby full of soft-boiled eggs."--Jimmy Kimmel, host of Jimmy Kimmel Live!

-

"[Stein] investigates the contemporary political landscape with a gimlet eye and plenty of humor in this deep dive into our cultural divide."Town and Country

-

"In this hilarious refereeing of the culture wars, former Time columnist Stein roams America studying wealthy, Ivy league-educated, conference-attending elites and their populist detractors...Stein's excellent reportage keeps the ideology light and is full of one-liners...that generously skew everyone. The result is an insightful, uproarious take on America's political divide."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"With his smart, self-deprecating humor, former Time columnist Stein investigates the correlation between the rise of populism and the delegitimization of expertise... In a world that seems so fragile, Stein makes a witty case for trained and trustworthy people running it."The National BookReview

-

"Joel Stein is a condescending bastard, but he's also very funny, insightful and correct. This book is a crucial argument for the importance of expertise in this world that increasingly rejects it. As Stein points out, it may feel good to go with the gut or follow popular opinion, but it does have its downsides. Like, for instance, causing a planetary apocalypse."--AJ Jacobs, the New York Times bestselling author of The Year of Living Biblically and The Know-It-All

-

"In these troubled times, we, as a nation, desperately need somebody to bring us together. Instead, we have Joel Stein, and this brilliantly funny book. So let's let somebody else unite us, while we let Joel Stein entertain the hell out of us."--Dave Barry, Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist and bestselling author of Dave Barry Turns 40

-

"Joel Stein makes a case for elitism over populism, but, contra what you might expect based on the subtitle, he does so without being condescending, without being smug...One of the most nuanced and introspective takes on populism post-2016 election, with Stein's typical humorous, easy to read style making the subject matter all the more accessible."Washington Free Beacon

-

"How can someone be so erudite and so funny at the same time? Read this book, be deeply offended by how much you laugh, then get yourself a chili dog to cleanse your intellectual palate. Then read it again. It's hilarious."Aisha Tyler, comedian, actress, and New York Times bestselling author

-

"As a white male Yale grad from New England who now lives in New York City and works in media, I feel like this book was written just for me. However, I will allow Joel Stein to publish other copies and sell you one because it really is that good!"John Hodgman, New York Times bestselling author

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use