Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

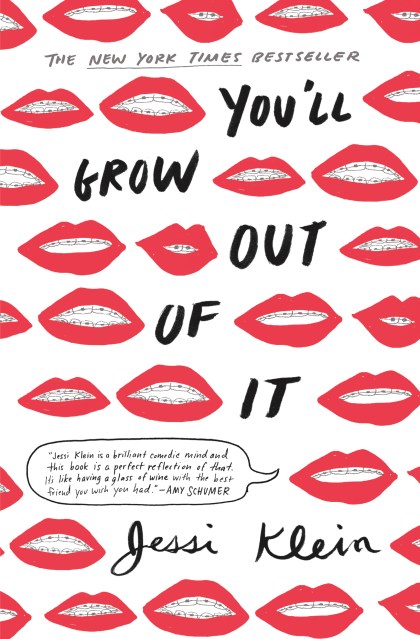

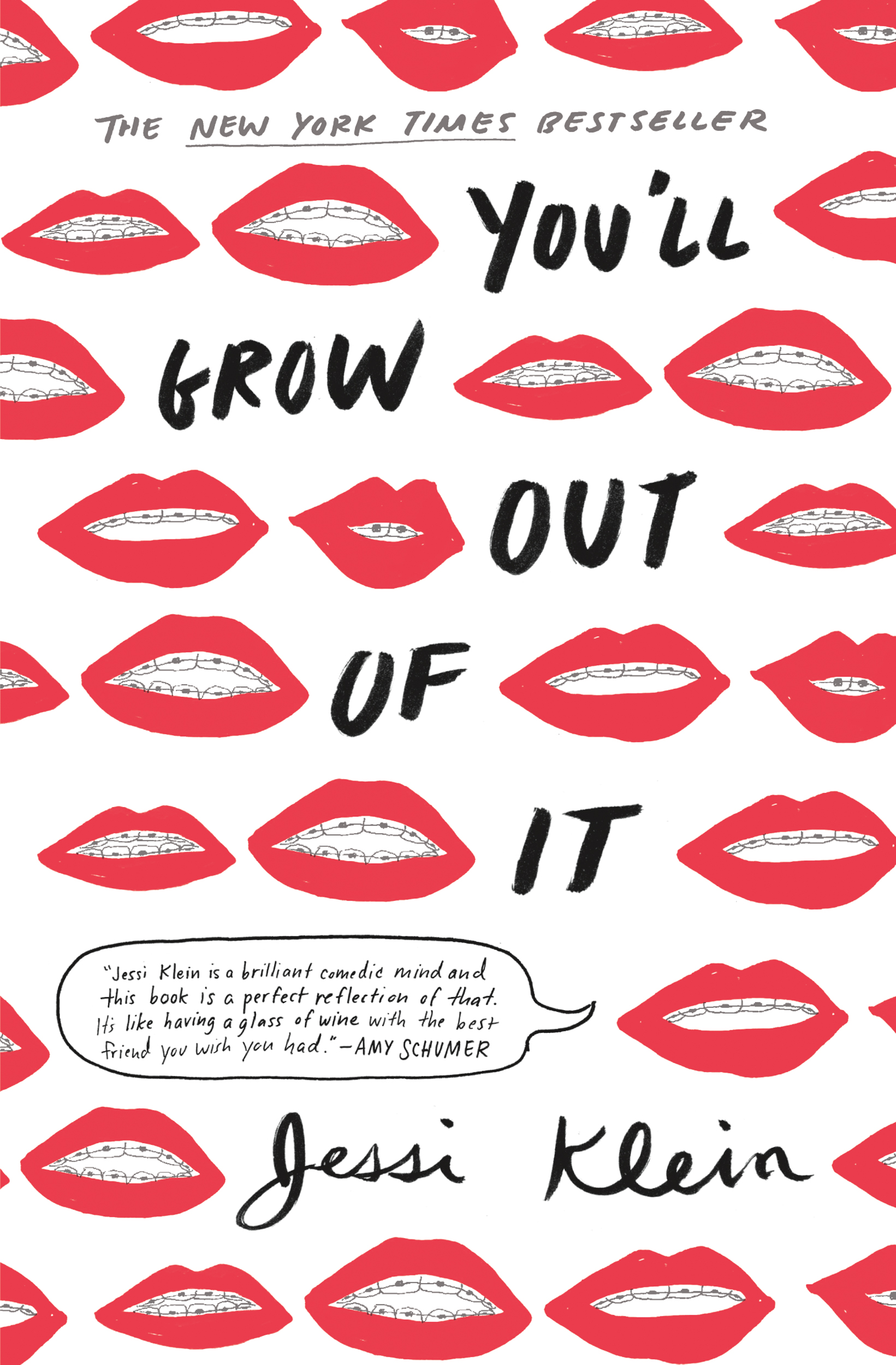

You'll Grow Out of It

Contributors

By Jessi Klein

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 12, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From Emmy award-winning comedy writer Jessi Klein, You’ll Grow Out of It hilariously and candidly explores the journey of the 21st-century woman.

As both a tomboy and a late bloomer, comedian Jessi Klein grew up feeling more like an outsider than a participant in the rites of modern femininity.

In You’ll Grow Out of It, Klein offers – through an incisive collection of real-life stories – a relentlessly funny yet poignant take on a variety of topics she has experienced along her strange journey to womanhood and beyond. These include her “transformation from Pippi Longstocking-esque tomboy to are-you-a-lesbian-or-what tom man,” attempting to find watchable porn, and identifying the difference between being called “ma’am” and “miss” (“miss sounds like you weigh 99 pounds”).

Raw, relatable, and consistently hilarious, You’ll Grow Out of It is a one-of-a-kind book by a singular and irresistible comic voice.

-

"Jessi Klein is a brilliant comedic mind and this book is a perfect reflection of that. It's like having a glass of wine with the best friend you wish you had."Amy Schumer

-

"YOU'LL GROW OUT OF IT does an amazing job making me understand what my life might be like if I were a woman. Or if I were Jessi Klein. I laughed. Lots. Not at what it's like to be a woman! That would be sexist. I laughed at the parts that you're supposed to. Which are plentiful. Because Jessi Klein is truly really funny."Ira Glass

-

"Never afraid to share insights and reveal the raw truth behind her own stories, Klein makes readers laugh while inspiring them, a feat that calls to mind the work of the late Nora Ephron. This uplifting and uproarious collection of personal essays will be repeatedly shared among friends."Publisher's Weekly (starred review)

-

"Reading [Jessi Klein's] book is like watching her--doubtless superb--stand-up act."Booklist (Starred Review)

-

"A gifted comedian turns the anxieties, obsessions, insecurities, and impossible-to-meet expectations that make up human nature into laughter."Kirkus (starred review)

-

"Fans of Amy Schumer (i.e., everybody?) will fall in love with funny-woman-and Emmy Award-winning Inside Amy Schumer writer-Jessi Klein's relatable collection of humor essays....Klein is a truly witty PRINZESS."Bust

-

"Klein shares her eccentric path to adulthood, from her tomboyish girlhood to sidesplitting dating tales and beyond in this uproarious, relatable, and irresistible memoir."Harper's Bazaar

-

"A book like Jessi Klein's YOU'LL GROW OUT OF IT comes along to remind us just what an artful confessional essay can do."New York Times

-

"Is it really a surprise that comedian Jessi Klein, head writer and executive producer for Inside Amy Schumer, would write a book of personal essays brimming with sharp observations and insights and poignant recollections but that above all is very, very funny? ...We guarantee that this book will quickly become one of your summer favorites."Entertainment Weekly

-

"[Jessi Klein's] astute, hilarious essays about the perilous path to modern womanhood will have you wincing in recognition."People

-

"Chances are Jessi Klein made you ugly-laugh... laugh even harder with the comedian's essay collection."Marie Claire

-

"Jessi Klein... delivers a collection of confessional and-of course, hilarious-autobiographical essays about her real-life experiences (showing her Spanxs at award shows!) with the same rat-a-tat-tat timing of her iconic comedy bits."Houstonia Magazine

-

"Her arguments are sharp, her confessions just light enough, and-most crucially-her quips LOL-worthy on almost every page."Vulture

-

"[Klein's] collection of mini rants strike that rare balance of honesty, brutality, and soul."Glamour

-

"Late bloomer? Tomboy? Award-winning writer for Inside Amy Schumer Jessi Klein is both, and in her memoir, YOU'LL GROW OUT OF IT, she'll make you laugh and maybe even wince a little in recognition as she relays life stories and lessons learned along her journey to womanhood."PopSugar

-

"Klein should be considered a front-runner to fill the void left behind by the late essayist Nora Ephron."Metro Canada

-

"This book, her first, is the kind you dog-ear to death because there are so many good lines."New York Post

-

"[Klein] hilariously deconstruct[s] and critique[s] typically feminine activities, from lingerie shopping to barre classes."Elle.com

-

"A sharp, witty collection of essays that will make you say, 'Same, TBH.'"Flare

-

"A must-read for former (and current) tomboys everywhere."Romper.com

-

"Authenticity, and a steady stream of truly laugh-out-loud lines... make Klein's new book of essays YOU'LL GROW OUT OF IT so much fun."The Seattle Times

-

"Deftly blending irreverent humor with poignant insights, Klein's writing is wonderfully intimate."New York Magazine

-

"It's heartfelt and funny in the same breath."Paste Magazine

-

"It's a witty, conversational, consume-in-one-sitting book about what it means to be a woman--or, in Klein's case, a 'tom-man.'"MTV.com

-

"[Jessi Klein] is so casually open at the most illuminating moments in her book that you feel you're sitting with a friend, wine glass in hand, picking up where you left off the Friday night before. It's the tagline of just about every female comic's memoir, but it rings especially true with Klein."The National Post

-

"An excellent showcase for her self-deprecating, transgressive humor."Toronto Star

-

"Jessi Klein is fiercely observant, self-deprecating, and just plain hilarious."A.V. Club

-

"Both smart and absurd, Klein's essays are written with a David Sedaris-like affinity for language."Winnipeg Free Press

-

"This collection of hilariously truthful life stories is by another in the lineage of female comedians turned memoir writers. Klein is a writer and producer for Inside Amy Schumer, and like the show, her essays offer a sharp commentary on womanhood in today's world."Boston Globe

- On Sale

- Jul 12, 2016

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455531196

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use