Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

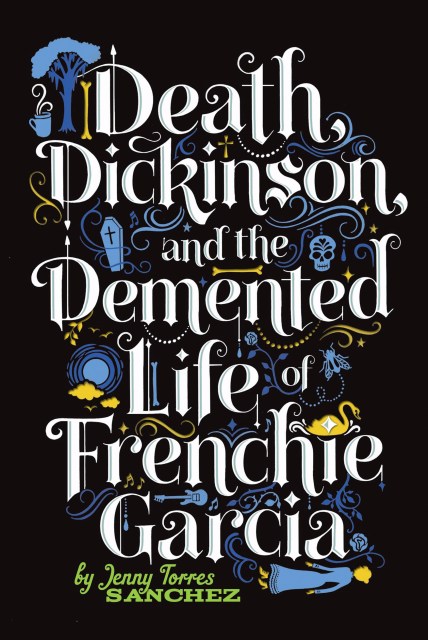

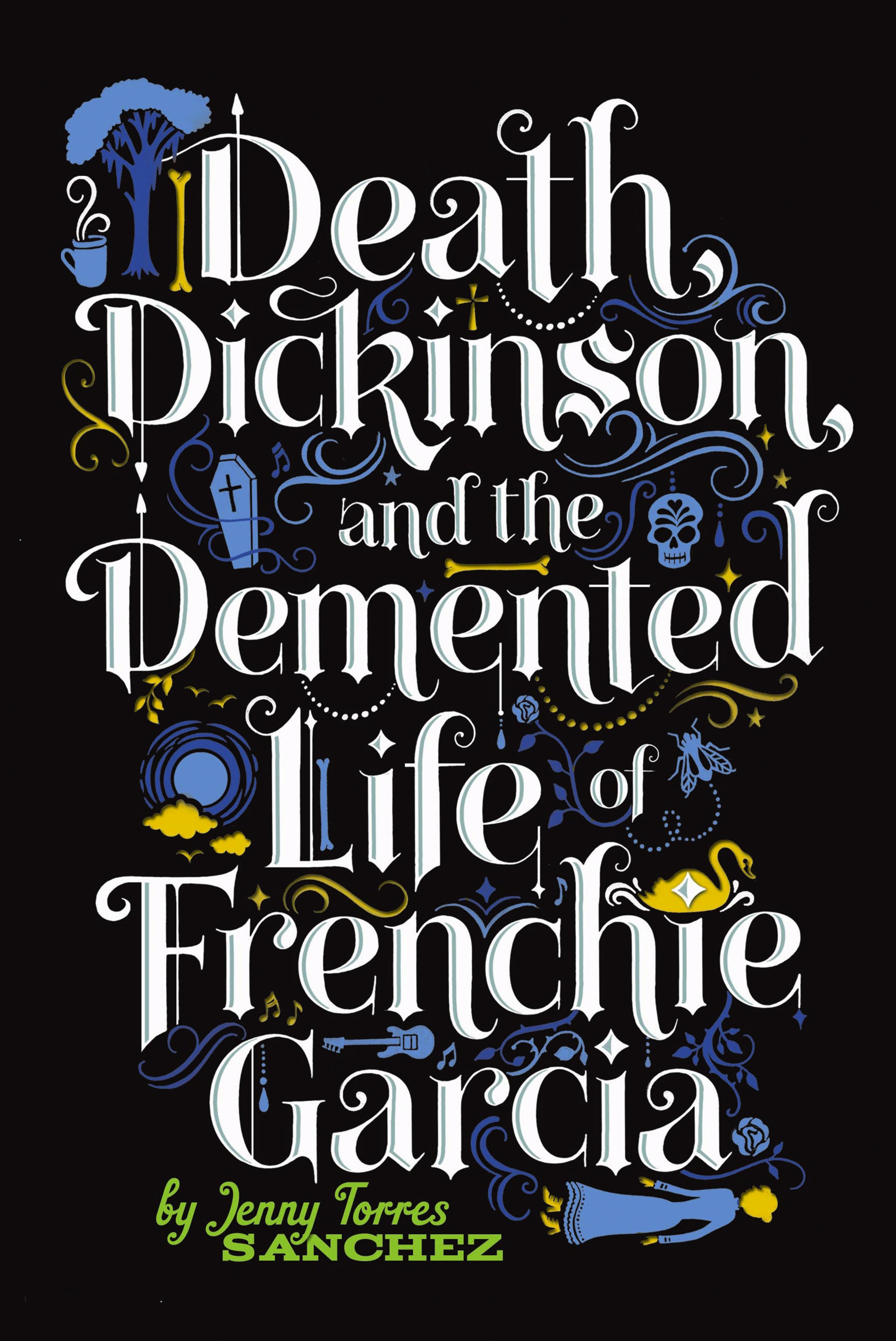

Death, Dickinson, and the Demented Life of Frenchie Garcia

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- ebook $8.99 $11.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 28, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When Frenchie’s guilt and confusion come to a head, she decides there is only one way to truly figure out why Andy chose to be with her during his last hours. While exploring the emotional depth of loss and transition to adulthood, Sanchez’s sharp humor and clever observations bring forth a richly developed voice.

Genre:

-

"Sanchez's expertly crafted narrative . . . [pulls] readers into Frenchie's anger and pain without straying into clichés of teen angst. . . . An exceptionally well-written journey to make sense of the senseless."—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“Sanchez (The Downside of Being Charlie) gets her heroine's tough exterior and vulnerable insides in just the right balance. . . . [She] provides a healing salve for teens who may know someone who has committed suicide, and also a strong testament against it.”—Shelf Awareness (starred review)

“This is a fast, well-written read with a satisfactory though not necessarily happy ending and a protagonist to remember-a survivor and person of action. A solid choice that is accessible even for reluctant readers.”

—School Library Journal

"With well-paced revelations, Sanchez gradually strengthens Frenchie's resolve to heal and move forward . . . and the author wittingly ensures that the reader wants nothing less for her."—Booklist

“Sanchez deftly maneuvers between real time and Frenchie's flashbacks, constructing a dreamy narrative that accurately captures the lingering repercussions of suicide."—The Horn Book Magazine

- On Sale

- May 28, 2013

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press Kids

- ISBN-13

- 9780762446803

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use