Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

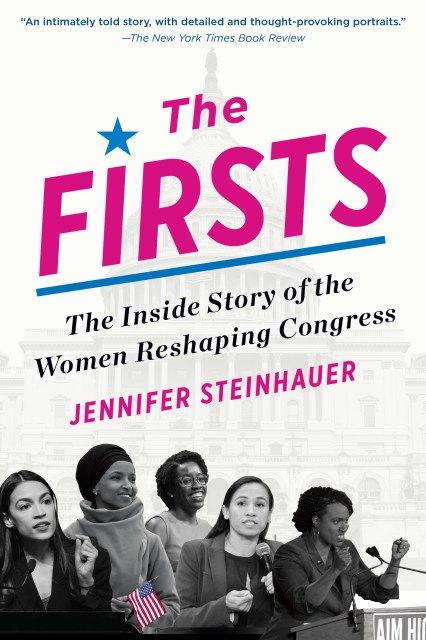

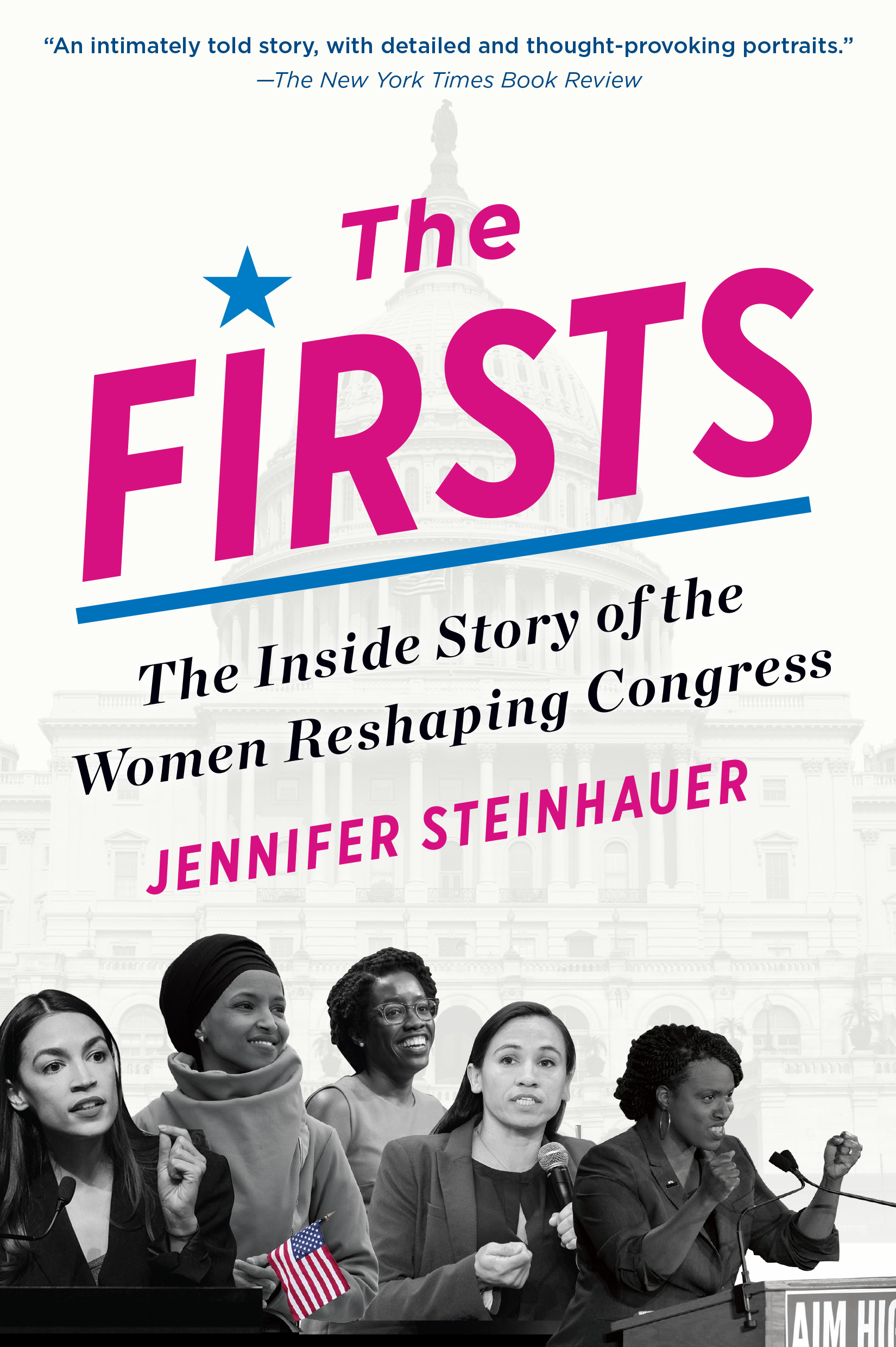

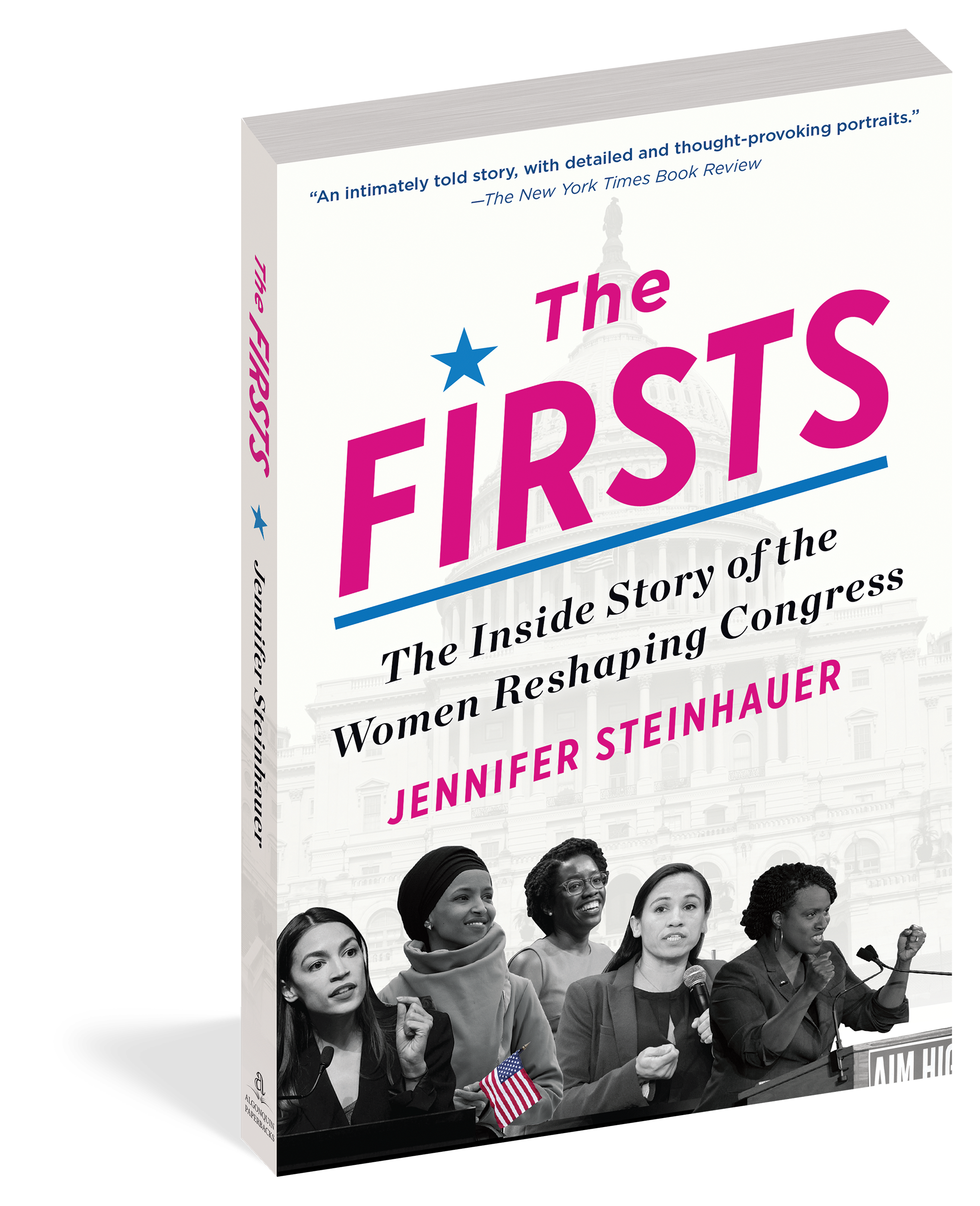

The Firsts

The Inside Story of the Women Reshaping Congress

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

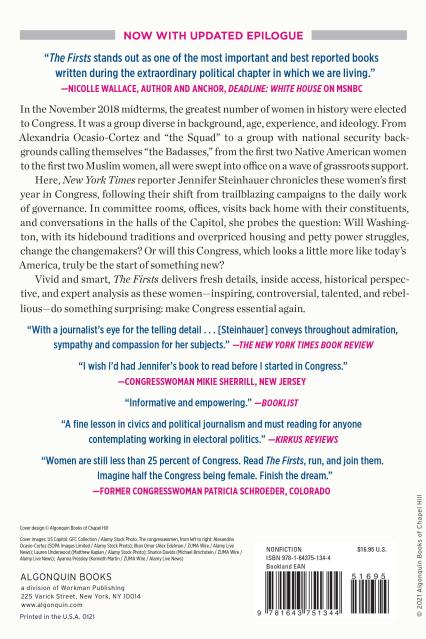

$16.95Price

$22.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.95 $22.95 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 19, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

—The New York Times Book Review

“The Firsts stands out as one of the most important and best reported books written during the extraordinary political chapter in which we are living.”

—Nicolle Wallace, author and anchor, Deadline: White House on MSNBC

NOW WITH UPDATED EPILOGUE

In the November 2018 midterms, the greatest number of women in history were elected to Congress. It was a group diverse in background, age, experience, and ideology. From Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and “the Squad” to a group with national security backgrounds calling themselves “the Badasses,” from the first two Native American women

to the first two Muslim women, all were swept into office on a wave of grassroots support.

Here, New York Times reporter Jennifer Steinhauer chronicles these women’s first year in Congress, following their shift from trailblazing campaigns to the daily work of governance. In committee rooms, offices, visits back home with their constituents, and conversations in the halls of the Capitol, she probes the question: Will Washington, with its hidebound traditions and overpriced housing and petty power struggles, change the changemakers? Or will this Congress, which looks a little more like today’s America, truly be the start of something new?

Vivid and smart, The Firsts delivers fresh details, inside access, historical perspective, and expert analysis as these women—inspiring, controversial, talented, and rebellious—do something surprising: make Congress essential again.

Genre:

-

“With a journalist’s eye for the telling detail, and valuable experience covering Congress for The New York Times, Steinhauer is often a few steps ahead of the newcomers. She conveys throughout admiration, sympathy and compassion for her subjects while they learn the hard way that hidebound traditions, a rigid seniority system and encrusted modes of governance do not yield readily to even the strongest convictions. The Firsts is an intimately told story, with detailed and thought-provoking portraits spliced in along the way. Steinhauer makes herself a character in her account, sharing with readers some witty and at times acerbic observations that keep the narrative moving along.”

—The New York Times Book Review

"Steinhauer provides an in-depth look at the women who historically changed the face and composition of Congress. Readers interested in women in politics and government will enjoy the book and appreciate the author’s thorough research."

—Library Journal

“Anyone interested in government, especially women in government, will find this book informative and empowering.”

—Booklist

“A fine lesson in civics and political journalism and must reading for anyone contemplating working in electoral politics.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“If suffragists, who got American women the right to vote 100 years ago, could watch our celebrations this year I am sure they would want people to read The Firsts. Why? Women are still less than 25% of Congress. Read The Firsts, run, and join them. Imagine half the Congress being female. Finish the dream.”

—Former Congresswoman Patricia Schroeder, Colorado

“The Firsts stands out as one of the most important and best reported books written during the extraordinary political chapter in which we are living. One part ‘you go, girl,’ one part ‘I feel your pain, sister,’ and one part ‘we are here to stay,’ it’s the most sweeping storytelling I’ve read about the 2018 class of women who arrived in Congress and have already left their mark.”

—Nicolle Wallace, author and anchor, Deadline: White House on MSNBC

- On Sale

- Jan 19, 2021

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781643751344

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use