By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

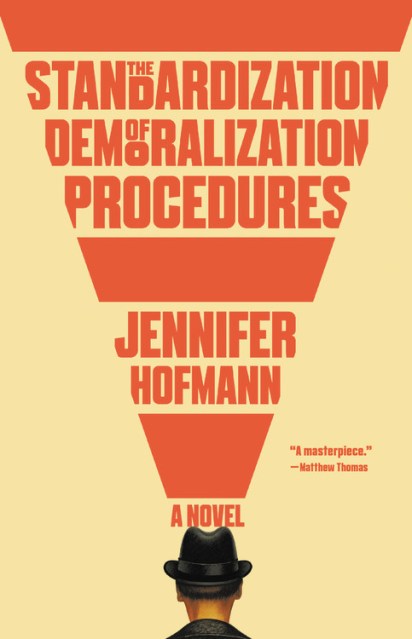

The Standardization of Demoralization Procedures

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 11, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316426459

Price

$27.00Price

$34.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 11, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A BuzzFeed Best Book of 2020

On November 9, 1989, Bernd Zeiger, a Stasi officer in the twilight of his career, is deteriorating from a mysterious illness. Alarmed by the disappearance of Lara, a young waitress at his regular café with whom he is obsessed, he chases a series of clues throughout Berlin. The details of Lara’s vanishing trigger flashbacks to his entanglement with Johannes Held, a physicist who, twenty-five years earlier, infiltrated an American research institute dedicated to weaponizing the paranormal.

Now, on the day the Berlin Wall falls and Zeiger’s mind begins to crumble, his past transgressions have come back to haunt him. Who is the real Lara, what happened to her, and what is her connection to these events? As the surveiller becomes the surveilled, the mystery is both solved and deepened, with unexpected consequences.

Set in the final, turbulent days of the Cold War, The Standardization of Demoralization Procedures blends the high-wire espionage of John le Carré with the brilliant absurdist humor of Milan Kundera to evoke the dehumanizing forces that turned neighbor against neighbor and friend against friend. Jennifer Hofmann’s debut is an affecting, layered investigation of conscience and country.

Genre:

-

“A story that John le Carré might have written for ‘The Twilight Zone,’ the tale of a spy who comes in from the cold while his world turns inside out… It’s not easy to make such a bureaucratic monster sympathetic, but by plumbing Zeiger’s existential crisis, Hofmann manages to reach his essential humanity… A rare novel that encourages you to read as though your sanity depends on it.”Ron Charles, Washington Post

-

“A gripping debut novel… Hofmann portrays [a] pervasive sense of syncope through rhythmic prose and powerful allusions to faith in an amoral world… she also establishes an effective tension between the German penchant for order and the sudden eruptions of chaos… Hofmann heightens this sense of entropy with evocative descriptions of people and places… [a sense of capsizing] reaches a pinnacle at the novel’s clever, dramatic end.”Dalia Sofer, New York Times Book Review

-

“Expertly crafted… I loved every… unpredictable minute of it.”Arianna Rebolini, BuzzFeed

-

“Nothing is as it appears and nobody is to be trusted . . . A clever and constantly surprising novel.”Kate Saunders, The Times

-

"Enrapturing... Hofmann constructs a beguiling tale of espionage... the novel hovers between genres like a subatomic particle between states. All the more impressive, Hoffman's exceptional debut never loses sight of the desires, mysteries, and small acts of rebellion that persist within dehumanizing systems."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"A remarkable first novel that reads like the work of a seasoned pro... Hofmann writes in assured prose of carefully chosen details that mark the best period fiction... she conjures up dark comedy in an understated, quirky satire of the Stasi's bureaucracy and cruelty and the paranoia that permeated East Germany."Kirkus (starred review)

-

"Gorgeous, dark, and haunted... a masterpiece of restraint, insight, and style... There is an extraordinary clarity of perception in these pages and one is astonished time and again at Jennifer Hofmann's prodigious gifts... It is a singular feat for a book about subject matter this chilling to make the reader feel so deeply; and yet that is part of the work of timeless literature, which is what this incandescent novel surely will come to be regarded as."Matthew Thomas, New York Times bestselling author of We Are Not Ourselves

-

"A beautiful and haunting novel that will linger in the minds of its readers... The Standardization of Demoralization Procedures challenges the reader to separate the fantastical from the merely bizarre. Is it the state or its citizens who are losing their minds? And how much repression can the human heart and soul withstand?"David Bezmozgis, author of the National Jewish Book Award winner The Betrayers

-

"A masterful waltz... an endlessly captivating puzzle... Despite the seemingly doomed world in which the novel takes place, Hofmann manages to dazzle us with brilliant humor, unrivaled insight, and fragments of hope. She recalls the prose brilliance of Jenny Erpenbeck, the philosophical curiosity of Milan Kundera, and the passion for the charming and the odd of Haruki Murakami... The Standardization of Demoralization Procedures is a hilarious, humanist, gorgeously written treatise on the currents that stir the human soul under the direst circumstances... I read this book in almost a single breath, and it is easily the best novel I've encountered this year, brilliant and funny and profound, producing some of the most complex, fascinating characters I've ever known... an instant classic."Jaroslav Kalfar, author of Spaceman of Bohemia, finalist for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, the Arthur C. Clarke Award, and the Dayton Literary Peace Prize

-

“Despite nourish trappings and some clever plot reversals, Hofmann’s novel is noteworthy not for its riff on the espionage-thriller genre, but for using a surreal historical moment to explore broader points about the collapse of ideals and the corrosiveness of secrecy.”Brendan Driscoll, Booklist

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use