Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

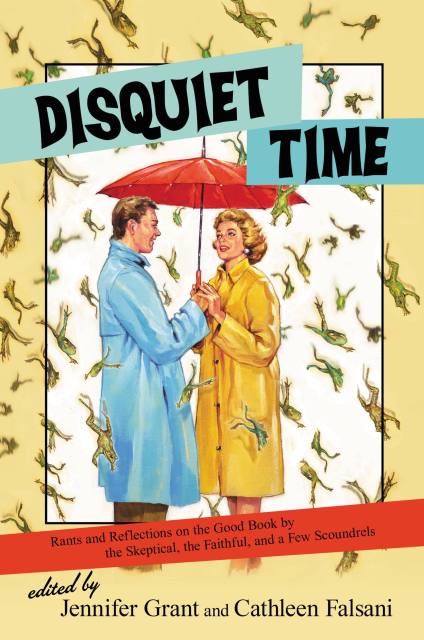

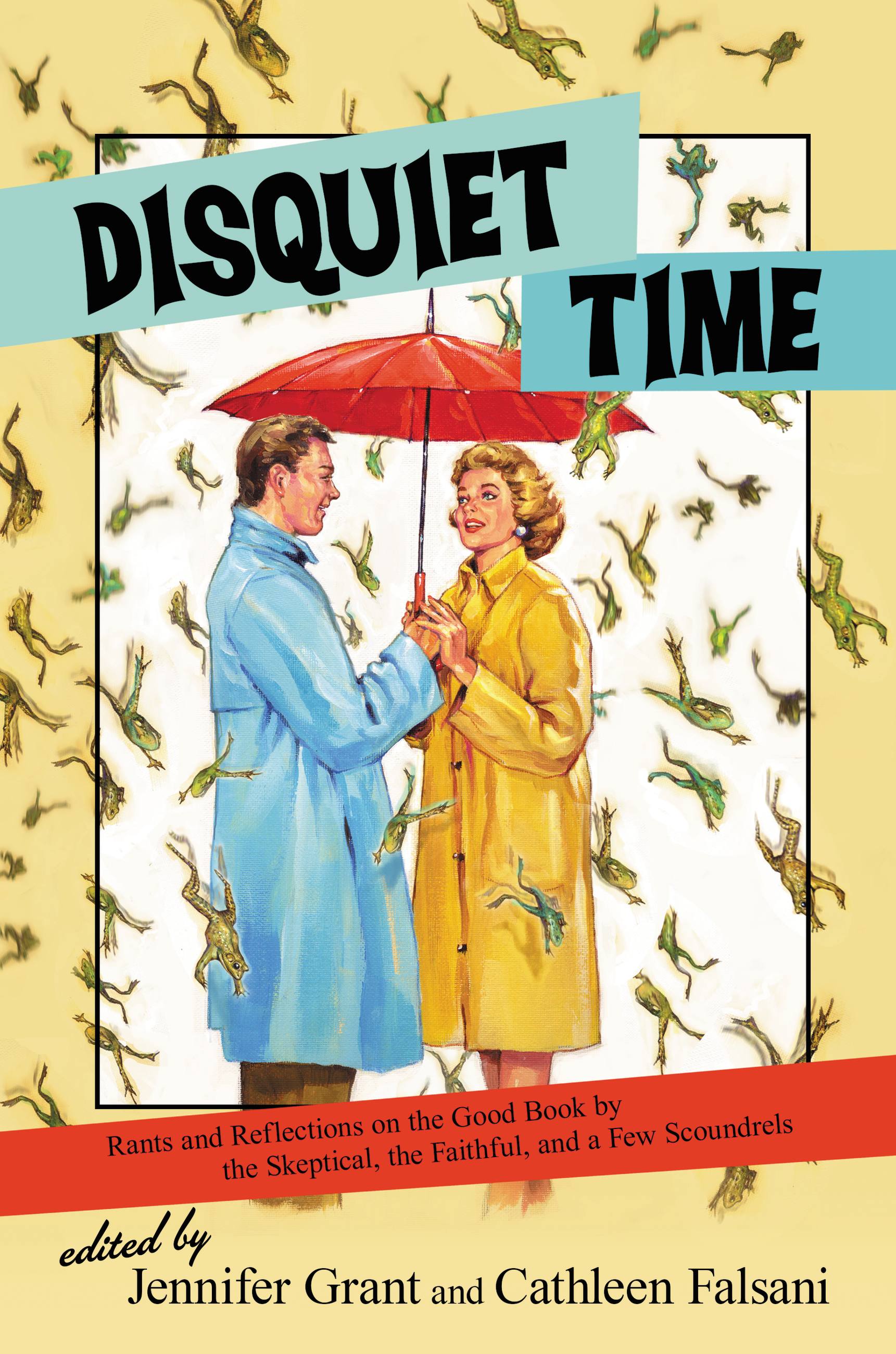

Disquiet Time

Rants and Reflections on the Good Book by the Skeptical, the Faithful, and a Few Scoundrels

Contributors

Edited by Jennifer Grant

Edited by Cathleen Falsani

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $24.00 $27.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 21, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

- What the heck is the book of Revelation really about? (The answer will surprise you.)

- How do we come to grips with the Bible’s troubling (or seemingly troubling) passages about the role of women?

- Why did the artist of the oldest known picture of Jesus intentionally paint him with a wonky eye — and what does it tell us about beauty?

Disquiet Time was written by and for Bible-loving Christians, agnostics, skeptics, none-of-the-aboves, and people who aren’t afraid to dig deep spiritually, ask hard questions, and have some fun along the way.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 21, 2014

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Jericho Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781455578849

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use