Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

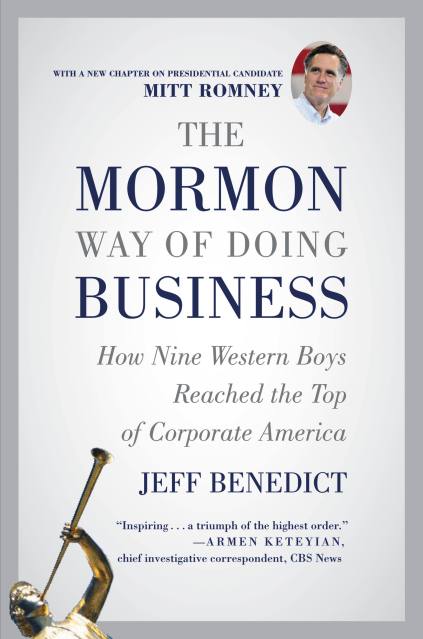

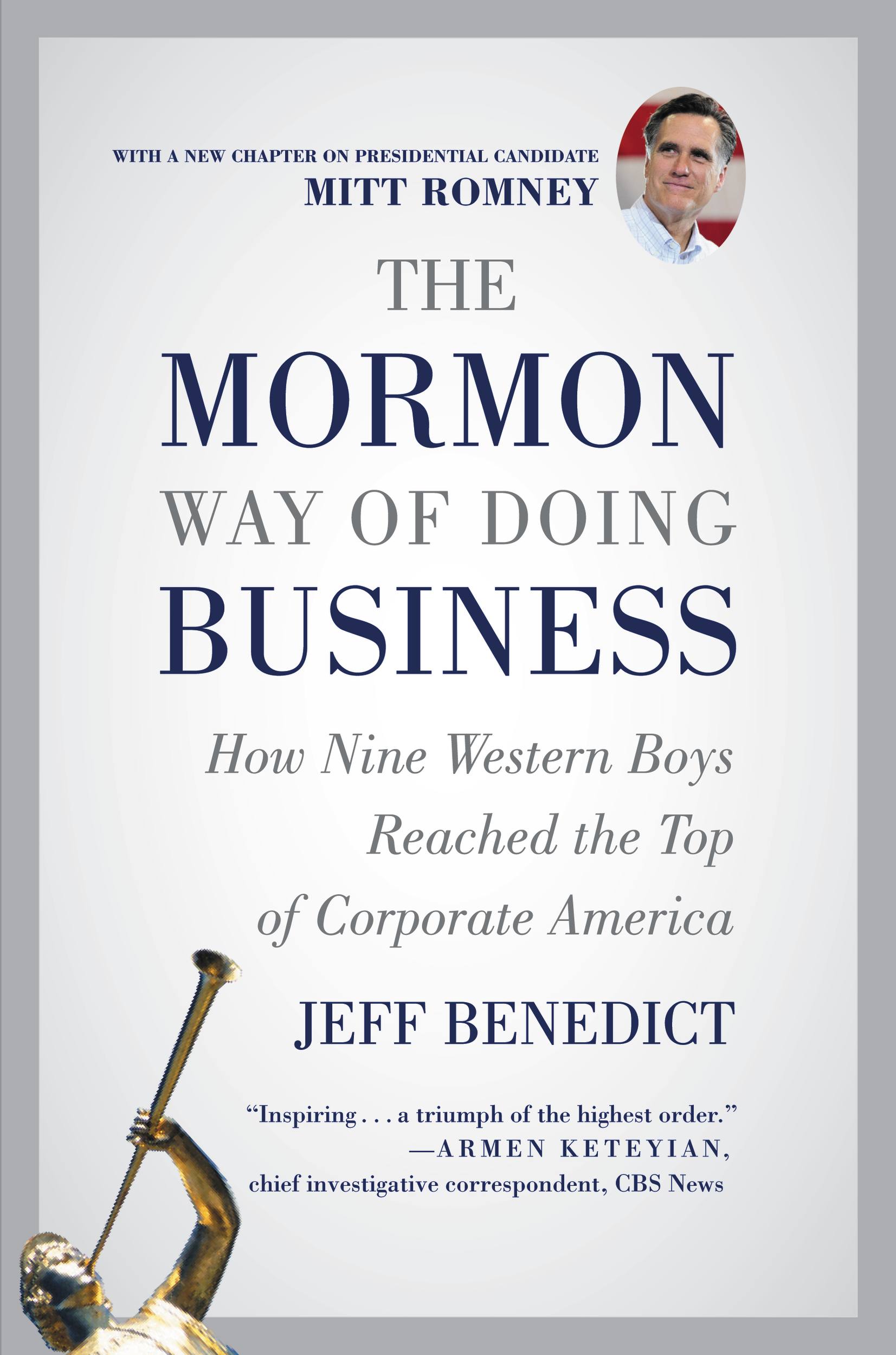

The Mormon Way of Doing Business

How Nine Western Boys Reached the Top of Corporate America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Abridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 3, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

An unprecedented look at how the Mormon faith has shaped some of today’s most successful CEOs and businessmen.

The Founder of JetBlue.The CEO of Dell Computers. The CEO of Deloitte & Touche. The Dean of the Harvard Business School. They all have one thing in common. They are devout Mormons who spend their Sundays exclusively with their families, never work long hours, and always put their spouses and children first. How do they do it? Now, critically acclaimed author and investigative journalist Jeff Benedict (a Mormon himself) examines these highly successful business execs and discovers how their beliefs have influenced them, and enabled them to achieve incredible success. With original interviews and unparalleled access, Benedict shares what truly drives these individuals, and the invaluable life lessons from which anyone can benefit.

The Founder of JetBlue.The CEO of Dell Computers. The CEO of Deloitte & Touche. The Dean of the Harvard Business School. They all have one thing in common. They are devout Mormons who spend their Sundays exclusively with their families, never work long hours, and always put their spouses and children first. How do they do it? Now, critically acclaimed author and investigative journalist Jeff Benedict (a Mormon himself) examines these highly successful business execs and discovers how their beliefs have influenced them, and enabled them to achieve incredible success. With original interviews and unparalleled access, Benedict shares what truly drives these individuals, and the invaluable life lessons from which anyone can benefit.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 3, 2007

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Business Plus

- ISBN-13

- 9780759516694

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use