By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

E.R. Nurses

True Stories from America's Greatest Unsung Heroes

Contributors

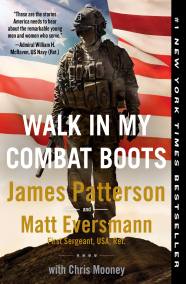

By Matt Eversmann

With Chris Mooney

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 11, 2021

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316301077

Price

$31.00Price

$39.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback (Large Print) $31.00 $39.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- Mass Market $10.99 $13.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 11, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Around the clock, across the country, these highly skilled and compassionate men and women sacrifice and struggle for us and our families.

You have never heard their true stories. Not like this. From big-city and small-town hospitals. From behind the scenes. From the heart.

This book will make you laugh, make you cry, make you understand.

When we’re at our worst, E.R. nurses are at their best.

“The compassion, the work ethic, and the selflessness of nurses … are given the respect they deserve and captured beautifully here.” —Sanjay Gupta, MD, neurosurgeon and chief medical correspondent, CNN

“James Patterson’s account of the twilight world between life and death that nurses inhabit is one of the most moving things I have ever read.” —Sebastian Junger, author of Freedom, The Perfect Storm, and In My Time of Dying

Series:

-

“As a trauma neurosurgeon, I have witnessed the compassion, the work ethic, and the selflessness of our nurses in countless situations. They save our lives every day and represent the true life blood of any hospital. Their stories are given the respect they deserve and are captured beautifully in E.R. Nurses.”Sanjay Gupta, MD, neurosurgeon and chief medical correspondent, CNN

-

"James Patterson's account of the twilight world between life and death that nurses inhabit is one of the most moving things I have ever read. In their own bullet-straight words, these heroes describe the pain, the love, and the brutally hard work of trying to save people's lives. I could not stop reading it and when I was done I felt like I was changed forever."Sebastian Junger, author of Freedom, Tribe, War, Fire, and The Perfect Storm

-

“E.R. Nurses captures the beating heart of nursing: the lives lost and saved, the hard tragedies and unbelievable miracles, and how every day nurses show up, give their all for patients, and then do it over and over and over again, all while holding onto their empathy and humanity. Readers will be stunned and moved by this no-holds-barred portrait of nurses' essential and deeply meaningful work.”Theresa Brown, PhD, RN, author of the New York Times bestseller The Shift: One Nurse, Twelve Hours, Four Patients' Lives

-

“These readable bite-sized snippets represent a significant caregiver demographic of women and men who exhibit the labor-intensive focus, compassion, dedication, and passion necessary to be an emergency nurse. From the heartfelt to the tragic, this book displays the nursing profession in all its unsung glory. A timely tribute to the modern-day heroes of medicine, conveyed in their own words.”Kirkus

-

“Thriller legend James Patterson has compiled hundreds of interviews for his poignant and timely nonfiction recounting of the dramatic, dangerous, and professional lives of America’s nurses.”Parade

-

"James Patterson and Matt Eversmann have captured the essence and drama of what it takes to be a nurse. Sometimes heartbreaking and sometimes frightening, give this book to someone who is thinking of being a nurse or is one already."The Florida-Times Union

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use