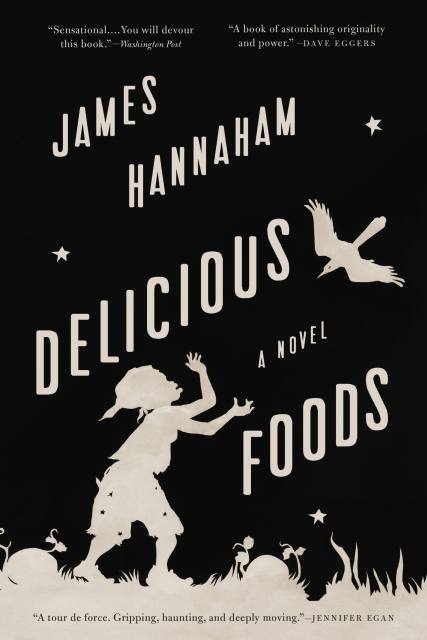

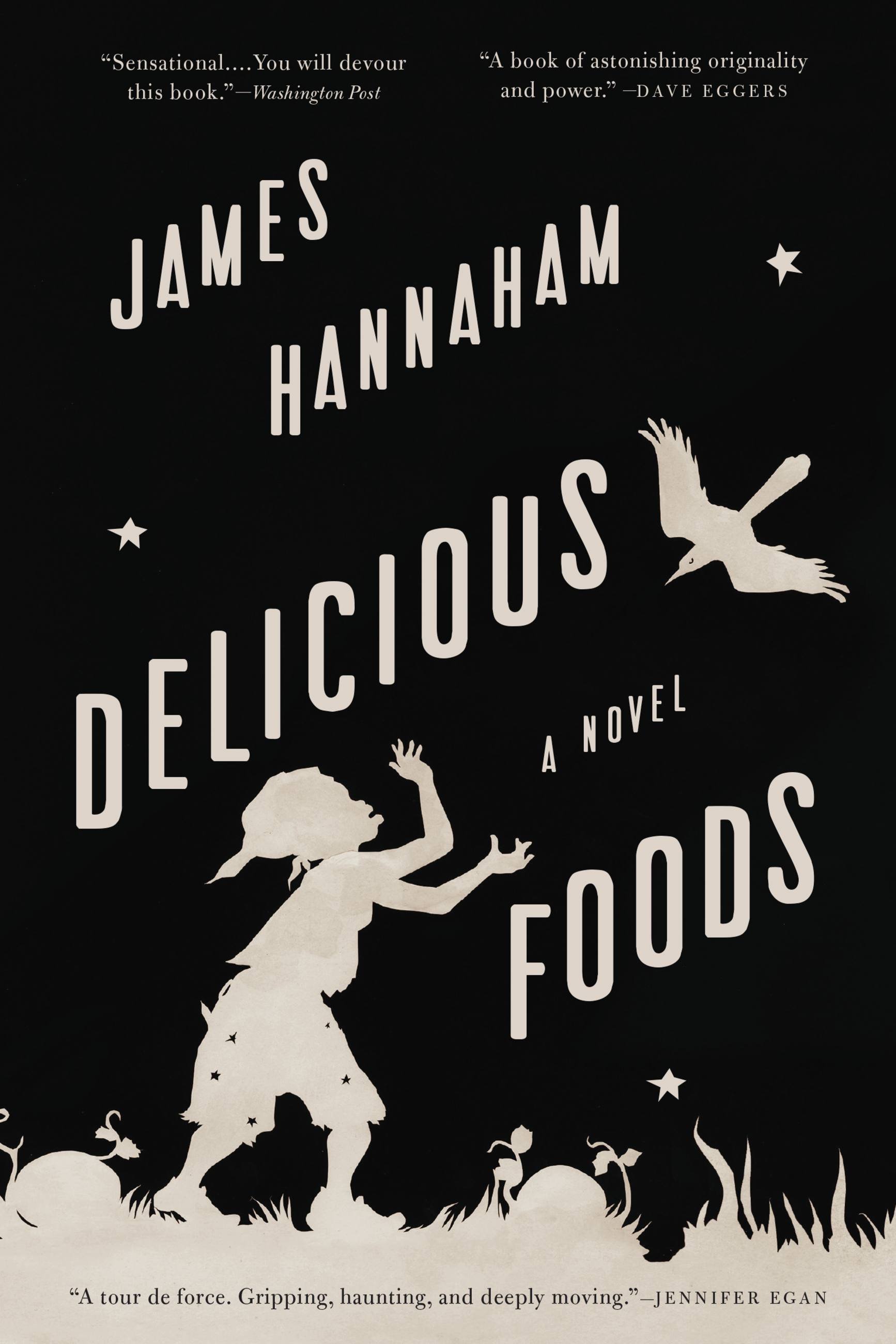

Delicious Foods

A Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 17, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Held captive by her employers — and by her own demons — on a mysterious farm, a widow struggles to reunite with her young son in this uniquely American story of freedom, perseverance, and survival.

Darlene, once an exemplary wife and a loving mother to her young son, Eddie, finds herself devastated by the unforeseen death of her husband. Unable to cope with her grief, she turns to drugs, and quickly forms an addiction. One day she disappears without a trace.

Unbeknownst to eleven-year-old Eddie, now left behind in a panic-stricken search for her, Darlene has been lured away with false promises of a good job and a rosy life. A shady company named Delicious Foods shuttles her to a remote farm, where she is held captive, performing hard labor in the fields to pay off the supposed debt for her food, lodging, and the constant stream of drugs the farm provides to her and the other unfortunates imprisoned there.

In Delicious Foods, James Hannaham tells the gripping story of three unforgettable characters: a mother, her son, and the drug that threatens to destroy them. Through Darlene’s haunted struggle to reunite with Eddie, through the efforts of both to triumph over those who would enslave them, and through the irreverent and mischievous voice of the drug that narrates Darlene’s travails, Hannaham’s daring and shape-shifting prose infuses this harrowing experience with grace and humor.

The desperate circumstances that test the unshakeable bond between this mother and son unfold into myth, and Hannaham’s treatment of their ordeal spills over with compassion. Along the way we experience a tale at once contemporary and historical that wrestles with timeless questions of love and freedom, forgiveness and redemption, tenacity and the will to survive.

Darlene, once an exemplary wife and a loving mother to her young son, Eddie, finds herself devastated by the unforeseen death of her husband. Unable to cope with her grief, she turns to drugs, and quickly forms an addiction. One day she disappears without a trace.

Unbeknownst to eleven-year-old Eddie, now left behind in a panic-stricken search for her, Darlene has been lured away with false promises of a good job and a rosy life. A shady company named Delicious Foods shuttles her to a remote farm, where she is held captive, performing hard labor in the fields to pay off the supposed debt for her food, lodging, and the constant stream of drugs the farm provides to her and the other unfortunates imprisoned there.

In Delicious Foods, James Hannaham tells the gripping story of three unforgettable characters: a mother, her son, and the drug that threatens to destroy them. Through Darlene’s haunted struggle to reunite with Eddie, through the efforts of both to triumph over those who would enslave them, and through the irreverent and mischievous voice of the drug that narrates Darlene’s travails, Hannaham’s daring and shape-shifting prose infuses this harrowing experience with grace and humor.

The desperate circumstances that test the unshakeable bond between this mother and son unfold into myth, and Hannaham’s treatment of their ordeal spills over with compassion. Along the way we experience a tale at once contemporary and historical that wrestles with timeless questions of love and freedom, forgiveness and redemption, tenacity and the will to survive.

-

"[A] sensational new novel about the tenacity of racism and its bizarre permutations... bounce[s] off the page with the sharpest, wittiest, most unsettling cultural criticism I've read in years... Hannaham is a propulsive storyteller... the whole story speeds through the dark... never takes its foot off the gas... An archetypal tale of American struggle... Reminiscent of Edward P. Jones's The Known World...[A] fantastically creative performance... [An] insightful and ultimately tender novel... You will devour this book."Ron Charles, Washington Post

-

"A writer of major importance... Moments of deft lyricism are Hannaham's greatest strength, and those touches of beauty and intuitive metaphor make the novel's difficult subject matter easier to bear... The novel's finest moments are... in the singular way that Hannaham can make the commonplace spring to life with nothing more than astute observations and precise language."New York Times Book Review

-

"Hannaham's prose is gloriously dense and full of elegant observations that might go unmade by a lesser writer. There is a great warmth in this novel that tackles darkness... [Hannaham] creates full-bodied characters. Even the minor figures are drawn with subtle details... Hannaham's decision to give a voice to crack--in the character Scotty--occasions some lively and inventive writing. Scotty has swagger and a sly sense of humor, and when he narrates he holds your attention... The character is complex, both tender and ruthless... A grand, empathetic, and funny novel about addiction, labor exploitation, and love... Delicious Foods should be read for its bold narrative risks, as well as the heart and humor of its author's prose."Roxane Gay, Bookforum

-

"Harrowing... Hannaham details a cycle of despair and enslavement in the poverty-ridden South... What emerges is the powerful tale of a place whose past is 'a ditch so deep with bodies it could pass for a starless night.'"The New Yorker

-

"Delicious Foods has plenty of magic in it, and plenty of tragedy... A powerful allegory about modern-day slavery, Delicious Foods explores the ways that even the most extraordinary black men and women are robbed of the right to control their own lives... [Hannaham] is serious about investigating the long-term effects of internalized racism, and the despair that prevents people from helping themselves... A sharp critique of the American belief that you can do anything as long as you work hard."Entertainment Weekly

-

"The novel's unforgettable cast... satisfies all our readerly cravings and without ostentation... The story's twists are at times implausible but nonetheless are a great feat of imagination. Hannaham has put his characters in the perfect conditions for these issues to play out--and for us to believe them... From what we've seen go down at Delicious, from the tenacity of this mother and son, we know it's love that keeps us going. Love is a rock every bit as hard as those diamond stars. Its indestructible beauty is enough to break down the earthly rocks that are its meager imitations."The Rumpus

-

"James Hannaham's satirical and darkly humorous look at racism, drugs, and the American South begins intensely... and doesn't let up... This brutal and beautiful tome is irresistible."USA Today

-

"Delicious Foods is not a story about the death of the American Dream, but an illumination of the fantasies that surround it, and the denial that permits us to believe in its innocence. It is also a compelling and haunting tale of family, responsibility, and endurance."Guernica

-

"An audacious, heartbreaking story... that is intended to be allegorical, but unearths a horror that is real and whose roots reach all the way back to slavery... Hannaham brilliantly creates a metaphor for human trafficking, modern-day industrialism, the pernicious effects of the war on drugs, and society's greedy need for 'quality' delivered as cheaply as possible... Delicious Foods stay[s] in the mind... A breathtaking depiction of how difficult is to break a spirit down, and how stubborn and resilient people can be. "Maclean's

-

"Strange and often haunting, Hannaham's brilliant look at the parent and child relationship, and the things that can tear that normally unbreakable bond apart, could be one of the best novels of 2015."Men's Journal

-

"Disturbing and addictive... This dark story is horrific, engrossing, deeply moving, and surprisingly funny at times... The subject matter in this tale of survival is uncomfortable and unfortunately all-too believable, but Hannaham's inventive storytelling and care for his characters fill this bleak world with much needed hope and love. Delicious Foods is hard to swallow at times, but also hard to put down."Winnipeg Free Press

-

"In lesser hands, Delicious Foods could easily have been a dark and dreary saga of misery and pain. Instead, Hannaham gleefully rides the lightness. There is no dwelling in sorry here--only movement to find a way forward to something better. No matter how bad things get, you are breathing, you are alive. Therein lies the joy."The Root

-

"Delicious Foods is a tale both hopeful and tragic, of the triumph of the human spirit, and the cruelties of man and nature...Delicious Foods is, above all else, an American story: a story of slavery and power, defiance and grit, and hope for a better day."Cedar Rapids Gazette

-

"Delicious Foods is an epic and devastating hero's journey... [It] is the result of a master storyteller at the top of his game. Don't miss it."Buzzfeed Books

-

"Hannaham's new book begins with one of the strongest openings for a novel in recent memory... Propelled by the force of the questions raised by those opening lines, Delicious Foods progresses with an almost hallucinogenic fervor."National Post

-

"This is a book of astonishing originality and power. In Delicious Foods, James Hannaham has created a wholly new world--a hallucinatory place shot through with struggle and terrible deeds--but one never lacking light or hope. Hannaham reinvents the Southern gothic with prose at once brutal and lyrical and drop-dead gorgeous. This is a hell of a novel."Dave Eggers, author of A Hologram for the King and The Circle

- Jennifer Egan, Pulitzer Prize winner for A Visit from the Goon Squad

-

"Delicious Foods is a strange and compelling American horror story, arrived at through fresh narrative strategies. A mother, a son, drugs, workers enslaved in a gruesome nightmare, love and survival--this is a wonderfully conjured novel."Daniel Woodrell, New York Times bestselling author of The Maid's Version and Winter's Bone

-

"Bury me with this book, so I will remember how wonderful living was--the food, the words, the stories, the places, the feeling of freedom. Delicious Foods is a magnificent novel, full of beauty a great writer can make of even the most terrifying parts of life."Rebecca Lee, author of Bobcat

-

"Delicious Foods is virtuosity on a hire wire--a wild, romping, brilliant plot, capped off with bodacious characters and breathtaking prose. A completely unforgettable, original, and singular novel by a brave, exciting new writer."Tayari Jones, author of Silver Sparrow

-

"A comic novel about family, addiction, and getting in too deep."O Magazine

-

"An audacious novel about poverty, grief, addiction and the bond between mother and son--told with a ferocious voice not unlike those of previous Discover selections Ruby by Cynthia Bond and Southern Cross the Dog by Bill Cheng."Shelf Awareness

-

"A Southern farm provides the backdrop for a modern-day slavery tale in this textured, inventive and provocatively funny novel... A poised and nervy study of race in a unique voice."Kirkus (starred review)

-

"Delicious Foods is fiercely imaginative and passionate. There are echoes here of Ralph Ellison and Zora Neale Hurston, even at times of Zola or Kafka. The investigation of Nat's disappearance is not the only instance of racism in law enforcement; in that respect, the novel is timely, even prophetic. Few novels leap off the page as this one does.Delicious Foods is a cri de coeur from a very talented and engaging writer."Bookpage (Top Pick of the Month)

-

"With its ragged Southern vernacular, clever personification, and horrific opening scene, Delicious Foods is violent and grim, but it's ultimately a reminder of how, amid poverty and addiction, love can prevail."Out Magazine

-

"If The Great Gatsby was the Great American Novel of the twentieth century, Delicious Foods could be that of the early twenty-first. If the plot sounds like tough going, Hannaham's masterpiece is anything but. The writing makes it "great," and the themes of pain, forgiveness, exploitation, and self creation make it American. It is simply unmissable."Booklist (starred review)

-

"Hannaham's seductive and disturbing second novel grips the reader from page one... The light he shines on the realities of racial injustice, human trafficking, drug abuse, and exploitation make a deep imprint on the reader. But as devastating as Darlene, Eddie, and the other laborers' situations become, the heroic themes of love, forgiveness, and redemption carry this memorable story."Publisher's Weekly (Starred Review)

-

"This talented author conveys the story as no other could, except possibly Tony Morrison, as in The Bluest Eye. But Hannaham may actually surpass Morrison's considerable talents in conveying the darkness of our struggles."Peter Kelton, The Examiner

- On Sale

- Mar 17, 2015

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316284929

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use