Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

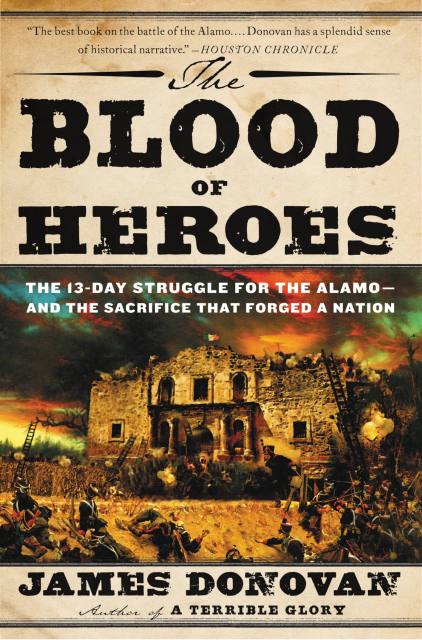

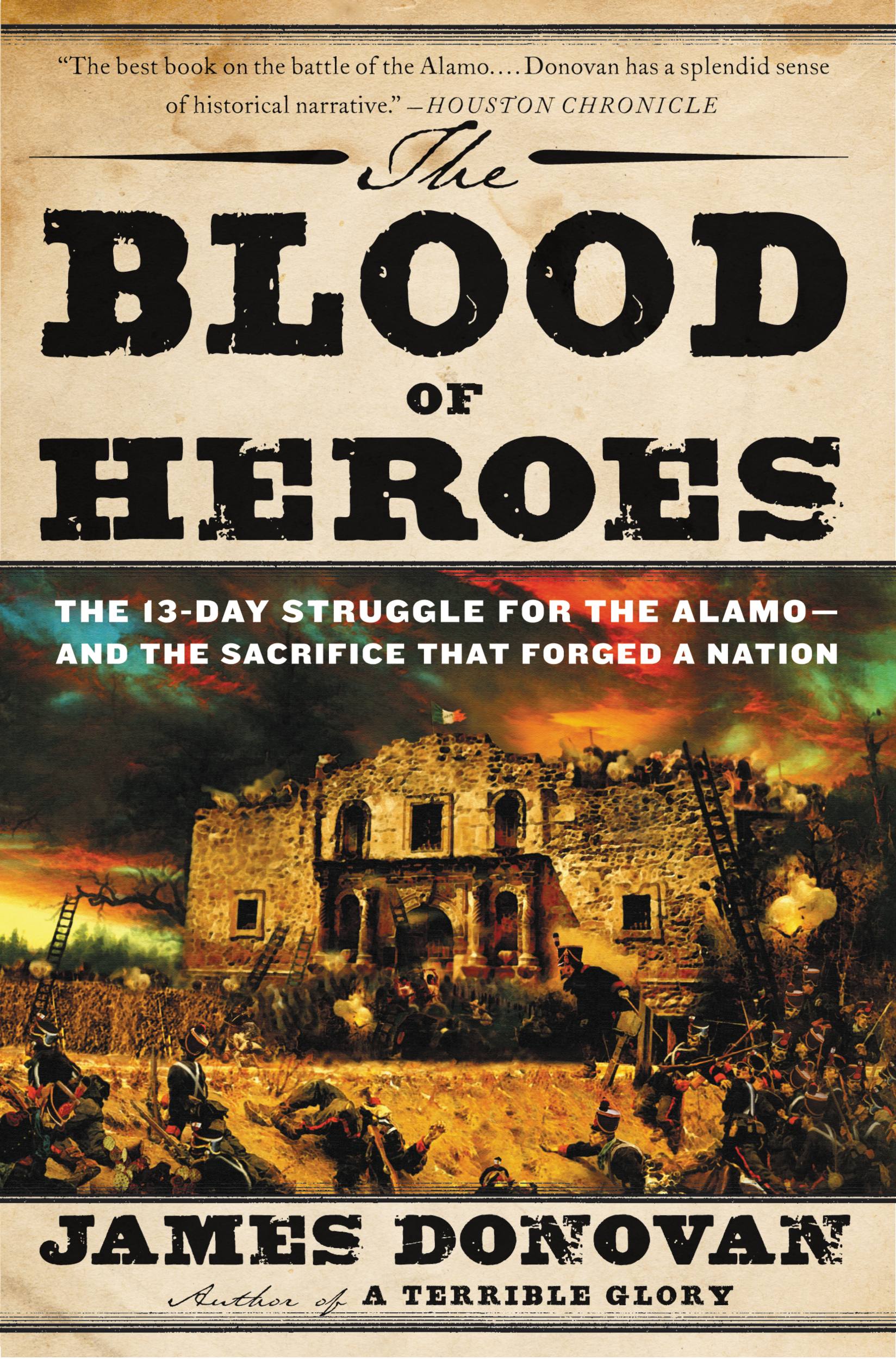

The Blood of Heroes

The 13-Day Struggle for the Alamo--and the Sacrifice That Forged a Nation

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $29.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 15, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

On February 23, 1836, a large Mexican army led by dictator Santa Anna reached San Antonio and laid siege to about 175 Texas rebels holed up in the Alamo. The Texans refused to surrender for nearly two weeks until almost 2,000 Mexican troops unleashed a final assault. The defenders fought valiantly-for their lives and for a free and independent Texas-but in the end, they were all slaughtered. Their ultimate sacrifice inspired the rallying cry “Remember the Alamo!” and eventual triumph.

Exhaustively researched, and drawing upon fresh primary sources in U.S. and Mexican archives, The Blood of Heros is the definitive account of this epic battle. Populated by larger-than-life characters — including Davy Crockett, James Bowie, William Barret Travis — this is a stirring story of audacity, valor, and redemption.

Exhaustively researched, and drawing upon fresh primary sources in U.S. and Mexican archives, The Blood of Heros is the definitive account of this epic battle. Populated by larger-than-life characters — including Davy Crockett, James Bowie, William Barret Travis — this is a stirring story of audacity, valor, and redemption.

- On Sale

- May 15, 2012

- Page Count

- 512 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316202541

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use