Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

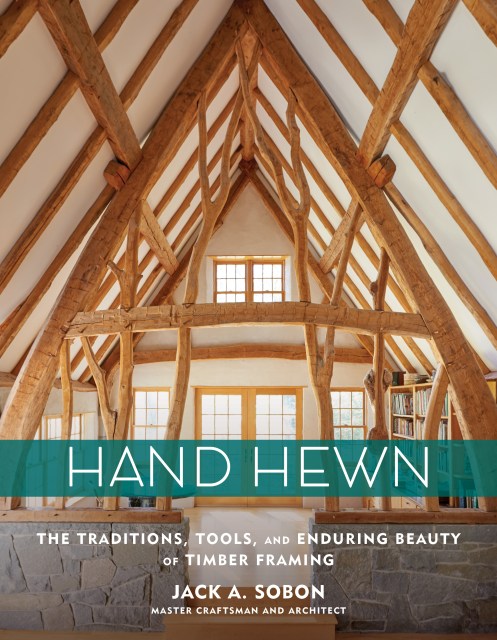

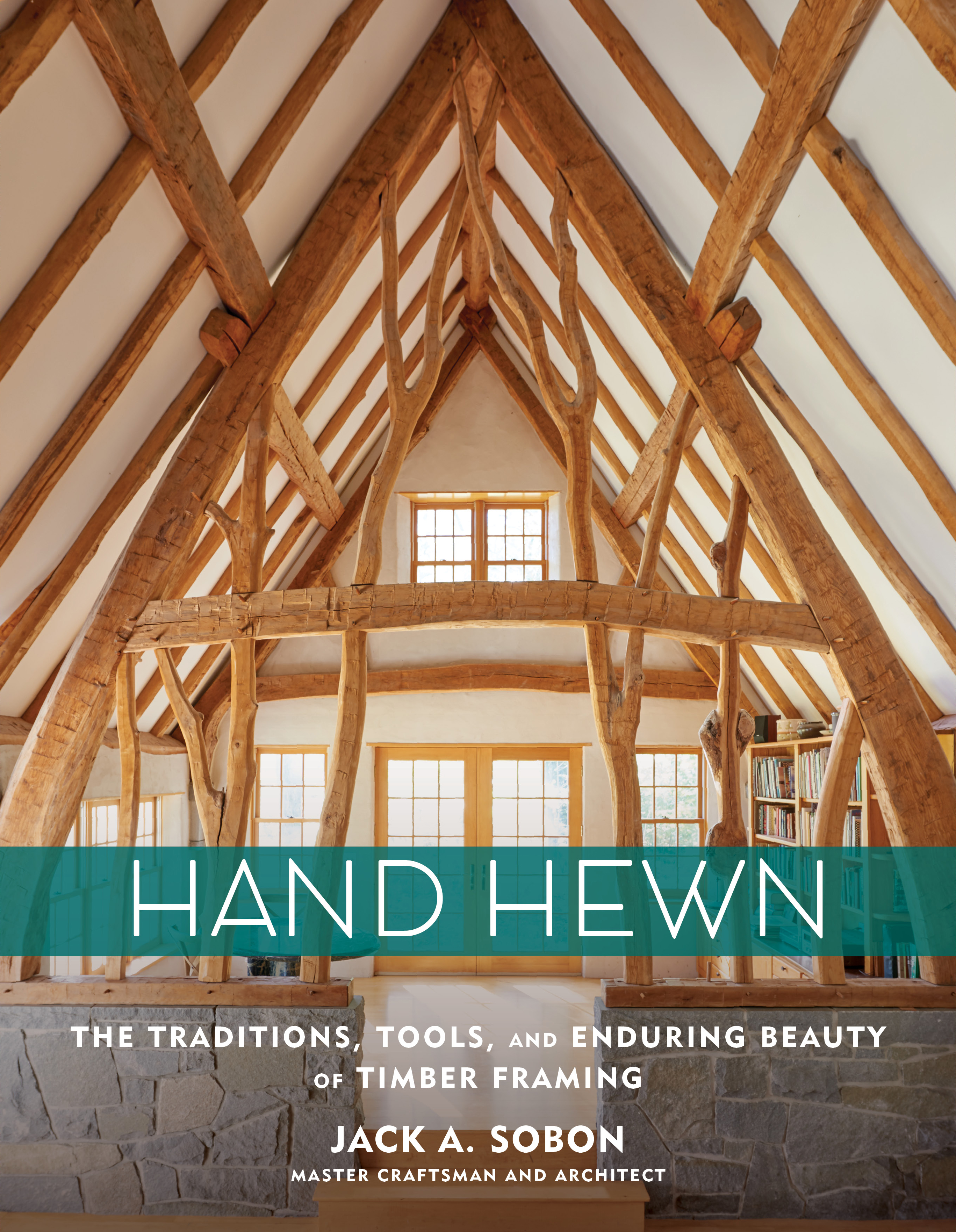

Hand Hewn

The Traditions, Tools, and Enduring Beauty of Timber Framing

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 15, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This publication conforms to the EPUB Accessibility specification at WCAG 2.0 Level AA.

Genre:

-

“Drawing on 7,000 years of tradition, Sobon, an architect who specializes in timber-frame buildings, showcases timber-framed porches, rooms, barns, and houses - all built without hammering a single nail.” — Publishers Weekly

“Sobon has spent his career turning trees into magnificent structural frameworks for buildings that satisfy our yearning for real strength, warmth, and honesty.” — Max Jacobson, architect and coauthor of A Pattern Language and Patterns of Home

“Hand Hewn is an invitation — through gorgeous photographs, clear drawings, and enticing text — to follow the passion and experience of a visionary master craftsman, historian, and poet whose work and philosophy are sure to inspire you.” — Philippe Petit, high wire artist and author of Man on Wire

“An essential book for every builder — of anything — revealing the world of timber framing from a true master craftsman.” — Will Beemer, author of Learn to Timber Frame and director of the Heartwood School for the

Homebuilding Crafts

- On Sale

- Oct 15, 2019

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9781635860016

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use