Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

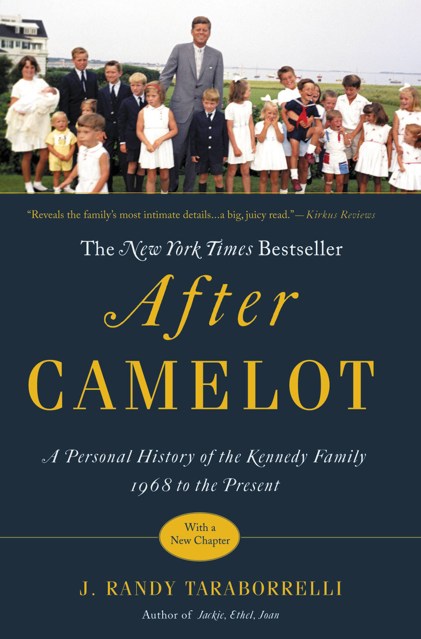

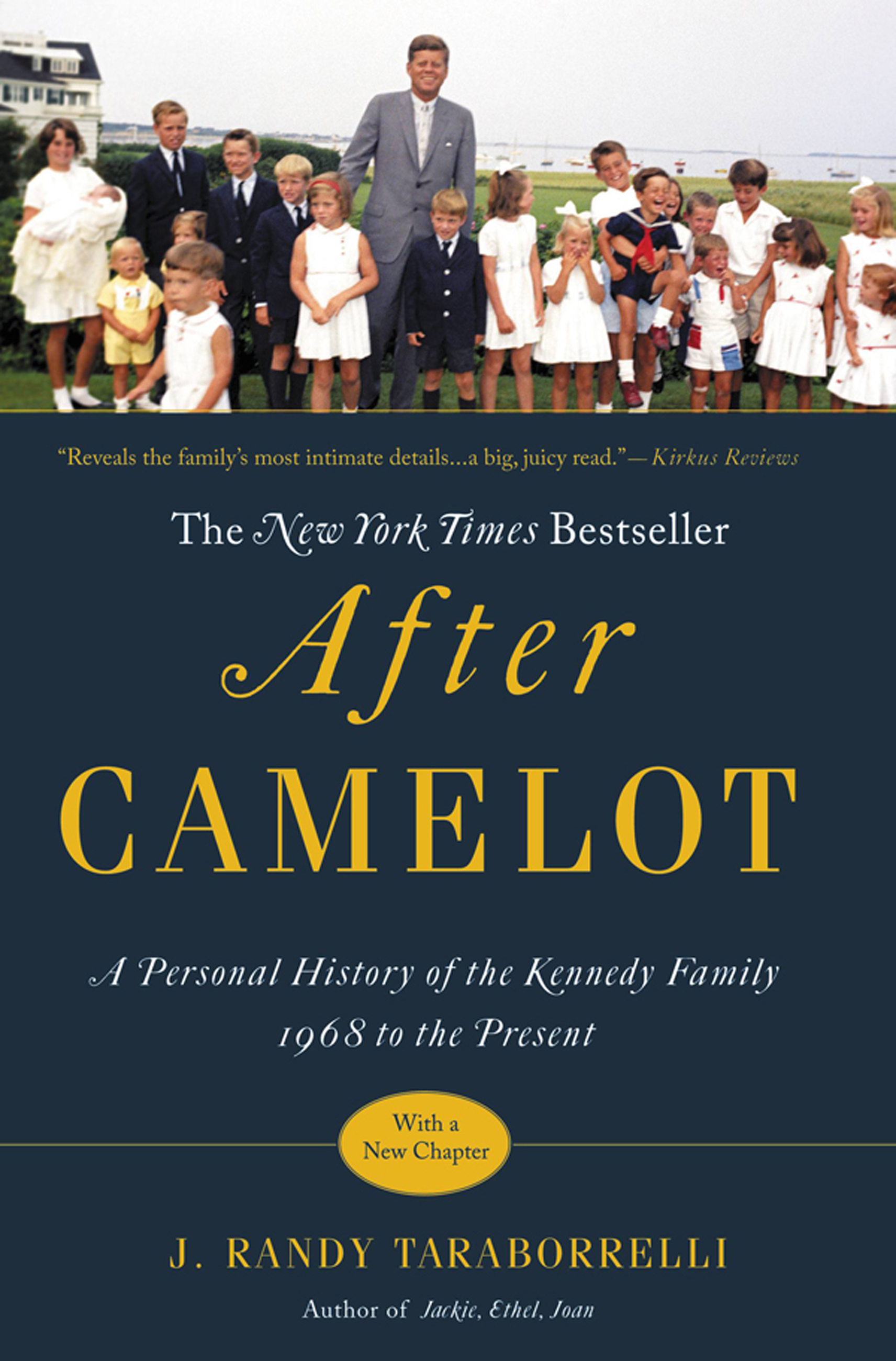

After Camelot

A Personal History of the Kennedy Family--1968 to the Present

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$6.99Price

$8.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 24, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

For more than half a century, Americans have been captivated by the Kennedys – their joy and heartbreak, tragedy and triumph, the dark side and the remarkable achievements. He describes the challenges Bobby's children faced as they grew into adulthood; Eunice and Sargent Shriver's remarkable philanthropic work; the emotional turmoil Jackie faced after JFK's murder and the complexities of her eventual marriage to Aristotle Onassis; the the sudden death of JFK JR; and the stoicism and grace of his sister Caroline.

He also brings into clear focus the complex and intriguing story of Edward "Teddy" and shows how he influenced the sensibilities of the next generation and challenged them to uphold the Kennedy name. Based on extensive research, including hundreds of exclusive interviews, After Camelot captures the wealth, glamour, and fortitude for which the Kennedys are so well known. With this book, J. Randy Taraborrelli takes readers on an epic journey as he unfolds the ongoing saga of the nation's most famous-and controversial-family.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 24, 2012

- Page Count

- 624 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446584432

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use