Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

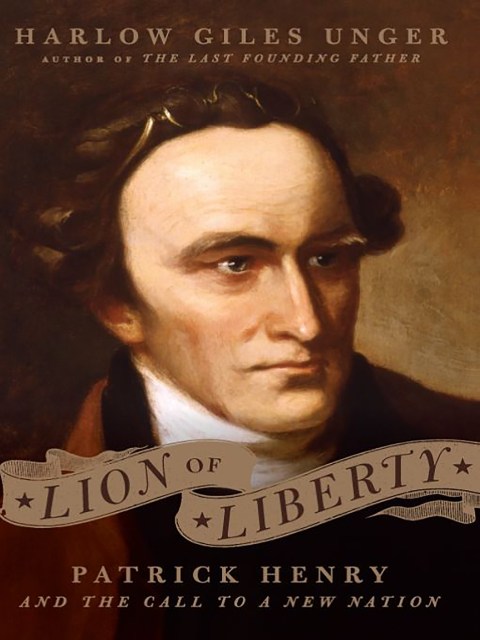

Lion of Liberty

Patrick Henry and the Call to a New Nation

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 26, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

As quick with a rifle as he was with his tongue, Henry was America’s greatest orator and courtroom lawyer, who mixed histrionics and hilarity to provoke tears or laughter from judges and jurors alike. Henry’s passion for liberty (as well as his very large family), suggested to many Americans that he, not Washington, was the real father of his country.

This biography is history at its best, telling a story both human and philosophical. As Unger points out, Henry’s words continue to echo across America and inspire millions to fight government intrusion in their daily lives.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 26, 2010

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306819346

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use