By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Do I Make Myself Clear?

Why Writing Well Matters

Contributors

Read by Greg Tremblay

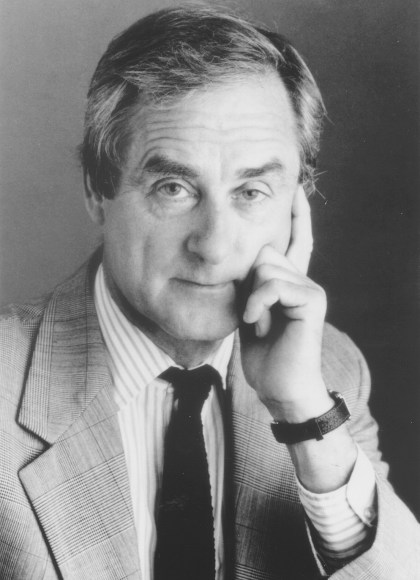

By Harold Evans

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 16, 2017

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478940654

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 16, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A wise and entertaining guide to writing English the proper way by one of the greatest newspaper editors of our time.

Harry Evans has edited everything from the urgent files of battlefield reporters to the complex thought processes of Henry Kissinger. He’s even been knighted for his services to journalism. In Do I Make Myself Clear?, he brings his indispensable insight to us all in his definite guide to writing well.

The right words are oxygen to our ideas, but the digital era, with all of its TTYL, LMK, and WTF, has been cutting off that oxygen flow. The compulsion to be precise has vanished from our culture, and in writing of every kind we see a trend towards more — more speed and more information but far less clarity.

Evans provides practical examples of how editing and rewriting can make for better communication, even in the digital age. Do I Make Myself Clear? is an essential text, and one that will provide every writer an editor at his shoulder.

Harry Evans has edited everything from the urgent files of battlefield reporters to the complex thought processes of Henry Kissinger. He’s even been knighted for his services to journalism. In Do I Make Myself Clear?, he brings his indispensable insight to us all in his definite guide to writing well.

The right words are oxygen to our ideas, but the digital era, with all of its TTYL, LMK, and WTF, has been cutting off that oxygen flow. The compulsion to be precise has vanished from our culture, and in writing of every kind we see a trend towards more — more speed and more information but far less clarity.

Evans provides practical examples of how editing and rewriting can make for better communication, even in the digital age. Do I Make Myself Clear? is an essential text, and one that will provide every writer an editor at his shoulder.

-

"Sir Harold Evans' memoir-cum-craft manual in which he rollicks - with all the joy and adventurousness of a rock 'n' roll tell-all...Of the truly silly number of hours I've spent with my nose in the binding of books on the craft of writing, those I spent with Do I Make Myself Clear? were the only I spent smiling, in search of someone I could read aloud to."NPR

-

"Mr. Evans's skills are on display on nearly every page of "Do I Make Myself Clear? Why Writing Well Matters." Writing a book about writing well can be hazardous for the author-reviewing one is risky, too-but in this case at least the author and his readers have nothing to fear."Edward Kosner, Wall Street Journal

-

"Have you heard of Harold Evans? Sir Harold Evans? Of course you have. He is one of the greatest and most garlanded editors alive....As a master editor and distinguished author, Evans is well qualified to instruct us on how to write well. But can he delight us in the process? After reading this book, I can affirm the answer is yes."Jim Holt, New York Times Book Review

-

"A writing manual so smart and incisive that it could surely benefit anyone-journalist, student, business executive, legislator-who has ever tried to craft an English sentence and fallen short."Malcolm Jones, Daily Beast

-

"Going well beyond the typical style guide's proscriptions against the passive voice, cliché, and so on, this polemic on writing takes the view that "the oppressive opaqueness" of much contemporary prose "is a moral issue."New Yorker

-

"Evans's book offers plenty of practical advice for those seeking to improve their writing skills, with a 10-point checklist to encourage a clear approach."Financial Times

-

"In the tradition of George Orwell, who said that political language is designed to make lies sound truthful, Harry Evans reminds us how important it is to write clearly. Then he shows how. Those of us who have been edited by Harry marvel at his dexterity in unclogging dense prose, and in this book he reveals his secrets."Walter Isaacson, author of Steve Jobs and The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

-

"A timely reminder that precision of language is the writer's greatest weapon. Harry Evans' methodical research and wry eye provide an entertaining lesson in intent, measured and exacting. At a time when public debate is shrill and filled by the overly assertive, Evans gives us a treat of a book that, through the use of practical examples, allows us to bathe in a language of clarity. Do I Make Myself Clear? shows that writing remains the gift of the ultimate explorer. Make more time for the journey."David Walmsley, Editor-in-Chief, The Globe and Mail

-

Harry Evans is one of the great -- indeed legendary -- editors of our time. Over the course of his career, he has edited newspapers, books and magazines, which surely qualifies as a publishing trifecta. All his talents -- and irresistible charm -- are on display in Do I Make Myself Clear? It's much more than a guide to English usage -- it's a companion: informative, delightful and indispensable. Do not hit INT or SEND without it!Christopher Buckley author of Thank You For Smoking

-

"Read this book before you write another word. As original as it is entertaining, Harold Evans' guided tour of every nuance of our language amounts to a masterly reappraisal of English usage for our times by a consummate editor turned writer."Anthony Holden editor of Poems that Make Grown Men Cry

-

Peggy Noonan author of The Time of Our Lives

"Harold (Harry) Evans is a writer and thinker of deep and celebrated accomplishment and marked independence, and his new book on how our government hides behind a word it's never even heard of- prolixity - is acutely on target." -

"The great French writer Émile Zola said that his prose style was "forged on the terrible anvil of daily deadlines," but the anvil of journalism is no use without the hammer of a great editor. Few if any wordsmiths hit harder than Sir Harold Evans. From the foggy corridors of Fleet Street to the lofty heights of Manhattan publishing, he has dedicated his life to hammering sloppy verbiage into plain English. Witty, wonderfully well written, but above all wise, Do I Make Myself Clear? should be required reading for all who scribble, type, or otherwise 'word process.' "Niall Ferguson, Senior Fellow, the Hoover Institution, Stanford

-

"Clarity and wit have something in common, and it's Harry Evans. He clears a path through the thorny underbrush that stands between us and meaning, and he does it with cutting humor and graceful charm. He certainly does make himself clear, and us, too."Alan Alda, Actor and Writer

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use