Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

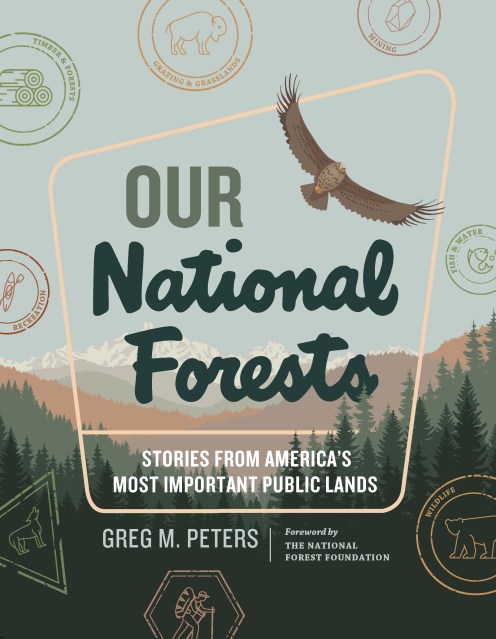

Our National Forests

Stories from America's Most Important Public Lands

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.95 $37.95 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 9, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Across 193 million acres of forests, mountains, deserts, watersheds, and grasslands, national forests provide a multitude of uses as diverse as America itself. They welcome 170 million visitors each year to hike, bike, paddle, ski, fish, and hunt. But “the people’s lands” offer more than just recreation. Lost habitats are recovered, timber is harvested, and endangered wildlife is protected as part of the Forest Service’s enduring mission.

In Our National Forests, Greg Peters gives an inside look at America’s most important public lands and the people committed to protecting them and ensuring access for all. From the Forest Service growing millions of seedlings in the West each year, to their efforts to save the hellbender salamander in Appalachia, the story spans the breadth of the country and its diverse ecology. And people are at the center, whether the dedicated Forest Service members or the everyday citizens who support and tend to the protected lands near their homes.

This complete look at America’s national forests—their triumphs, challenges, controversies, and vital programs—is a must-read for everyone interested in the history of America's most important public lands.

Genre:

-

“Provides new and fascinating information on the country’s large expanse of public lands.” —Travel Writers Magazine

“Peters urges readers to act as citizen-agents to fight on behalf of these lands.” —Landscape Architecture

“Greg brings decades of lived and professional experience to bear in this outstanding narrative. With both historic and personal references in the sweeping arch of thoughtful natural resource management, this remarkable book offers a practical guide to encourage conscientious environmental stewardship for all to follow.” —James Edward Mills, author and National Geographic Explorer

“This beautifully illustrated and gracefully written book demonstrates how vital these complex landscapes and their fraught place in US environmental culture are.” —Char Miller, Pomona College, author of America’s Great National Forests, Wildernesses, and Grasslands

“In Greg Peters’s hands, the subject of the United States National Forests comes alive as a history of America, at turns humbling and tragic, but ultimately an inspiring reminder of the incredible resource that is our public lands.” —Brendan Leonard, author of The Camping Life and Surviving the Great Outdoors

- On Sale

- Nov 9, 2021

- Page Count

- 280 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643261256

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use