Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

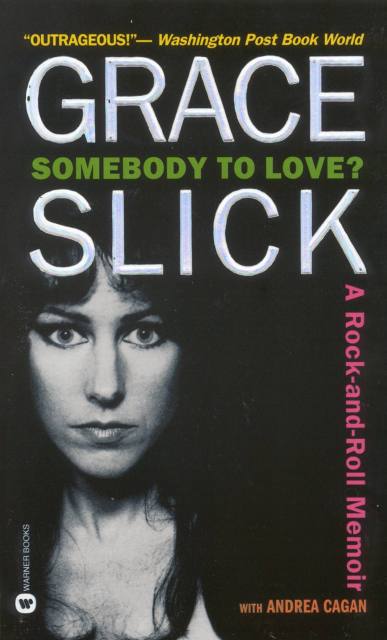

Somebody to Love?

A Rock-and-Roll Memoir

Contributors

By Grace Slick

By Andrea Cagan

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $14.98

- Mass Market $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 14, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

She has been called rock and roll’s original female outlaw, as famous for her bad behavior as for her haunting singing voice. In her 25-year career as a musician, Grace Slick charted dozens of hits and sold millions of albums. From “White Rabbit” and “Somebody to Love” to “Sarah” and “Miracles”, the songs she performed became the anthems of a generation.

Whether describing her antics at the White House with Abbie Hoffman or the unforgettable experience that was Woodstock, Slick’s recollections have the same rich imagery found in her lyrics. In this provocative narrative, readers will discover the many sides of Grace Slick: as artistic pioneer; she records songs with Jerry Garcia and David Crosby; as practitioner of freedom and rebellion; she sleeps with Jim Morrison and gets arrested for DUI on three separate occasions (without actually being in a car); and as a loving mother to actress China Kantner, she tries to balance casual friendship with parental wisdom.

Slick offers a revealing self-portrait of the complex woman behind the rock-outlaw image, and delivers a behind-the-scenes, no-holds-barred view of the people and spirit that defined a quarter-century of American pop culture. Wildly funny, candid, and evocative, Somebody to Love?tells what it was really like during, and after, the Summer of Love-and how one remarkable woman survived it all to remain today as vibrant and rebellious as ever.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Dec 14, 2008

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446554428

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use