Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

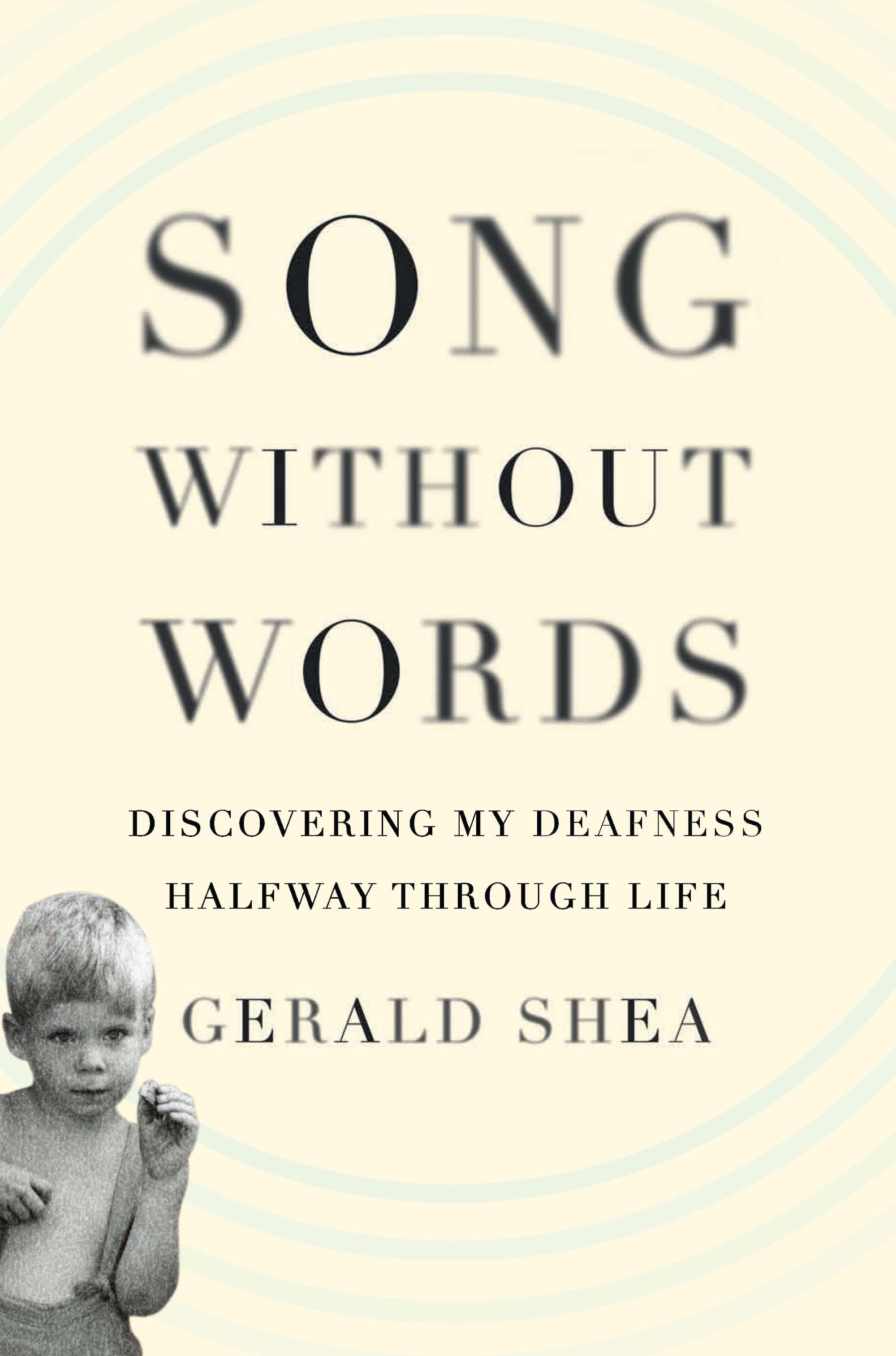

Song Without Words

Discovering My Deafness Halfway through Life

Contributors

By Gerald Shea

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $38.00 $48.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 26, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Gerald Shea’s witty and candid memoir of how he compensated for his deafness — through sheer determination and an amazing ability to translate the melody of vowels. His experience gives fascinating new insight into the nature and significance of language, the meaning of deafness, the fierce controversy between advocates of signing and of oral education, and the longing for full communication that unites us all.

Genre:

-

“Both a work of literary art and a manual for understanding the difficult world Shea inhabits…Readers are lucky that Shea took the time to write this masterful memoir, which brings us into a hidden world so few have ever visited. Song without Words proves that memoir, at its lyrical best, can be a truly wonderful and inspirational literary genre.”

Charleston Post and Courier, 2/10/13

“Shea's determination allows him to manage his impairment with remarkable success, and readers will be surprised at how it escaped the attention of his parents, brothers, friends, and teachers.”

Washington Post, 3/3

“[A] brilliant and thoroughly engaging, if often painful, account…Throughout Song Without Words, the author candidly describes his dark, even catastrophic moments of perceived failure—failure to hear, failure to understand and interpret correctly, failure to connect, failure to keep up—but despite all this, the book sings a long, clear note of success. It is not a complaint but an exploration, not only of one man's unique path to self-knowledge but also of the nature of communication itself….To read Song without Words is to appreciate the poetry and clarity of Shea's language, resonant with hard-won experience, wisdom and stunning courage.”

The New Statesman

-

Nominated for the National Book Critics Circle's John Leonard Award for Best First Book

Finalist, Nonfiction (All Authors), New England Book Festival

Antonia Fraser, author of My Life with Harold Pinter

"A brilliant window into the largely unknown world of the partially deaf: riveting to read, and illuminating at every level.”

Louis Begley, author of About Schmidt

“Fascinating, heartbreaking, heroic, and relentlessly riveting.”

Kirkus Reviews, 1/15/13

“The moving, poignant account of how a brilliant lawyer came to terms with the midlife discovery of his own partial deafness…The book is a powerful expression of loss, acceptance and the very human need to communicate. Shea's narrative derives its true power from the eloquence and intelligence with which he illuminates a world that may be unfamiliar to many readers.”

David Lodge, author of Deaf Sentence: A Novel

"Song Without Words is [an] incredible story . . . . Gerald Shea . . . tells it with eloquence, wit, and the narrative drive of a good novel. It is a unique contribution to the growing literature about deafness, one which will illuminate the experience of fellow-sufferers, and deepen understanding in society at large.”

Boston Globe, 2/22/13

-

“Shea…writes with elegance, finesse, and humor.”

Action on Hearing Loss (UK), Summer 2014

“Shea has presented us with a cogent, beautifully literate and breakthrough book of the philosophy of being a partially deaf person.”

Sante Fe New Mexican, 5/10/13

“The struggle alone would make good reading, but it's Shea's infusion of his experience with music and his explorations of the very nature of language that make this book cross into fascinating. And since 30 million Americans have some hearing loss, the story is probably closer to home than you realize.”

Psychology Today blog, 5/2813

“[Shea] writes beautifully, and his reflections on partial hearing loss are insightful and often very moving…Song Without Words is compelling reading.”

The Spectator (UK), 6/22/13

“Shea's story, fascinating and unusual in some of its details, gives a valuable insight into the experience of many.”

New York Journal of Books, 6/24/13

“What makes [Song without Words] shine is the sparkling of humor throughout, the addition of glimpses into his personal life, and the easing of what might be considered arrogance by tastefully illustrating his kindness and humility. You just can't help but like this man.”

-

“Humans communicate. It's not second nature, it's nature. Without that, what is it like to be human? Shea's Song Without Words is as eloquent an answer as we are likely to get.”

Library Journal, 3/15/13

“An inspiring and thought-provoking read.”

Booklist, 2/27/13

“Fascinating…[Shea's] story gives one a renewed appreciation for both the ear and the human spirit.”

Philadelphia Tribune, 3/1/13

“Witty and candid…Brings fascinating new insight into the nature and significance of language, the meaning of deafness—and the fierce controversy between advocates of signing versus those who favor oral education.”

Hudson Valley News, 2/27/13

“Well told…Shea [comes] to terms with his mid-life discovery with wisdom, wit, and the uncanny ability to make his story fascinating to all of us.”

InfoDad.com, 3/7/13

“Fascinating reading.”

Grand Piano Passion, 4/16/13

“Gives a poetic window into the everyday struggles of a person with a significant hearing loss, yet also shows the way for living with a loss with acceptance, creativity, and even joy.”

American Lawyer (website), 4/19/13

“Elegantly written.”

Millbrook Independent, 5/28/14 -

"[A] captivating memoir."Jerome Groopman, New York Review of Books

- On Sale

- Feb 26, 2013

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306821943

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use