Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

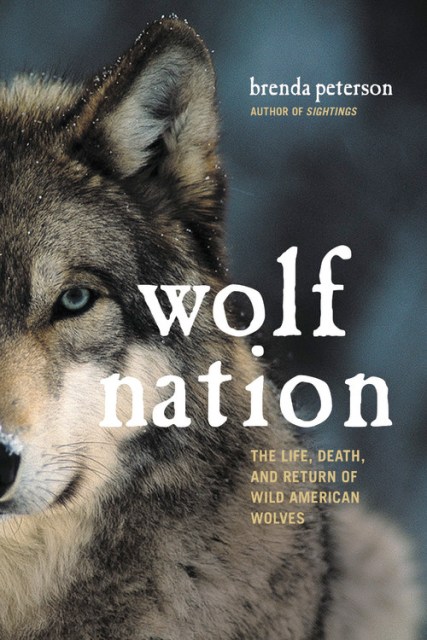

Wolf Nation

The Life, Death, and Return of Wild American Wolves

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$37.00Price

$47.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 2, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In the tradition of Peter Matthiessen’s Wildlife in America or Aldo Leopold, Brenda Peterson tells the 300-year history of wild wolves in America. It is also our own history, seen through our relationship with wolves. The earliest Americans revered them. Settlers zealously exterminated them. Now, scientists, writers, and ordinary citizens are fighting to bring them back to the wild. Peterson, an eloquent voice in the battle for twenty years, makes the powerful case that without wolves, not only will our whole ecology unravel, but we’ll lose much of our national soul.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 2, 2017

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306824937

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use