By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

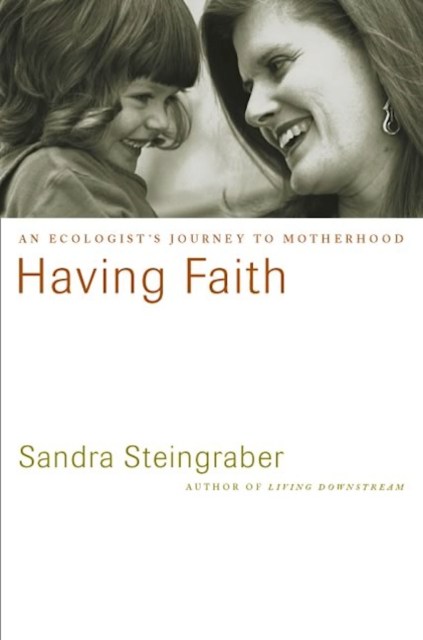

Having Faith

An Ecologist's Journey to Motherhood

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 15, 2012

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780738216621

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $8.99 $11.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 15, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A brilliant writer, first-time mother, and respected biologist, Sandra Steingraber tells the month-by-month story of her own pregnancy, weaving in the new knowledge of embryology, the intricate development of organs, the emerging architecture of the brain, and the transformation of the mother’s body to nourish and protect the new life. At the same time, she shows all the hazards that we are now allowing to threaten each precious stage of development, including the breast-feeding relationship between mothers and their newborns. In the eyes of an ecologist, the mother’s body is the first environment, the mediator between the toxins in our food, water, and air and her unborn child.Never before has the metamorphosis of a few cells into a baby seemed so astonishingly vivid, and never before has the threat of environmental pollution to conception, pregnancy, and even to the safety of breast milk been revealed with such clarity and urgency. In Having Faith, poetry and science combine in a passionate call to action.A Merloyd Lawrence Book

Series:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use