By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

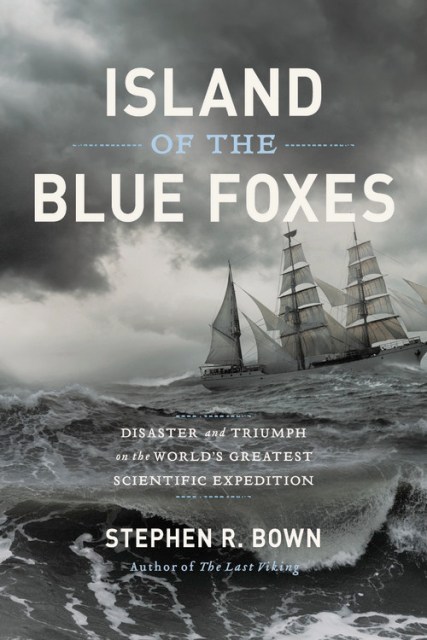

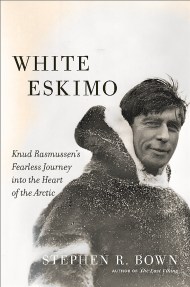

Island of the Blue Foxes

Disaster and Triumph on the World's Greatest Scientific Expedition

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 7, 2017

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306825194

Price

$28.00Format

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00

- ebook $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 7, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The immense 18th-century scientific journey, variously known as the Second Kamchatka Expedition or the Great Northern Expedition, from St. Petersburg across Siberia to the coast of North America, involved over 3,000 people and cost Peter the Great over one-sixth of his empire’s annual revenue. Until now recorded only in academic works, this 10-year venture, led by the legendary Danish captain Vitus Bering and including scientists, artists, mariners, soldiers, and laborers, discovered Alaska, opened the Pacific fur trade, and led to fame, shipwreck, and “one of the most tragic and ghastly trials of suffering in the annals of maritime and arctic history.

Series:

-

"A gripping account of 'the most extensive scientific expedition in history,' whose impressive results were certainly matched by its duration and miseries. A rapidly paced story of adventure 'to be appreciated as a reminder of the power of nature and of the struggle and triumph over disaster...and of the powerful urge to persevere and return home.'"Kirkus Reviews

-

"[An] excellent work of historical reconstruction that will enamor fans of the Age of Exploration."Booklist

-

"Island of the Blue Foxes is a rip-roaring tale of adventures, hardship, sacrifice, human hubris and--dare I say--madness...set in inhospitable landscapes and told with breezy energy. Wonderful."Andrea Wulf, author of The Invention of Nature: Alexander Humboldt's New World

-

"One of the most significant and harrowing expeditions in the annals of European and American exploration, the Bering voyages remain largely unknown to modern readers. Inspired by the European Enlightenment, Peter the Great and his successor Empress Anna sent Danish navigator Vitus Bering 5,000 miles eastward across Siberia, then another 3,000 miles across the Pacific to the unknown coasts of North America, decades before Captain Cook's well-known voyages. Bering left his name on a sea and a strait, and his naturalist Steller identified dozens of unknown plants and animals in the New World, but perhaps the most inspiring legacy is the remarkable forbearance and human ingenuity employed by the expedition's survivors in the face of scurvy, starvation, and shipwreck. A gifted chronicler of Northern exploration, Stephen Bown tells this incredible tale with grace, authority, and a deep grasp of its significance."Peter Stark, author of Astoria: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson's Lost Pacific Empire

-

"Bown's readable history should elevate Bering into the top tier of explorers. For fans of adventure, exploration, and discovery."Library Journal

-

"[A] little-known, white-knuckle tale of ambition, ingenuity and the raw fight for survival. Bown has a stellar track record of chronicling the larger-than-life tales of explorers...An amazing story, both in its intimate details of day-to-day adventure and survival and its large-scale political and scientific implications."Calgary Herald

-

"Brings North American readers into a part of history seldom written about anywhere."CBC News

-

Rocky Mountain Outlook

"A worthwhile read and perhaps one of [Bown's] best. In sharing what is a remarkable story of Arctic exploration, Bown has added a welcome addition to what is already a rich catalogue of books about the Arctic and maritime exploration." -

"[Bown] has weaved a story which details the highs and lows of one of the greatest expeditions in world history and one which has been largely forgotten by mainstream humanity. Consequently, this book is an opportunity for all to learn about Bering and his contributions to the geographic and scientific knowledge gained as a result of his efforts."New York Journal of Books

-

"Well-written, fast-paced."Portland Book Review

-

"The story of [an] epic undertaking...It should draw new readers to a neglected chapter in maritime history. Bering's voyage shows the lengths to which humans are driven by their curiosity, and demonstrates the environmental consequences of our greed."Nature

-

"[An] engrossing narrative...Naturalist Georg Willhelm Steller['s]...heroics, and the story of his mates' survival, so expertly recalled by Bown, exemplifies the unstoppable momentum of human curiosity."Minneapolis Star Tribune

-

"Bown has drawn on journals, logs, letters and official reports to piece together a story never fully told before. And what a story: adventure and discovery, misery and death, and a cast of characters by turns admirable and appalling, brilliant and hopeless, annoying and plain nasty."New Scientist

-

"The curious tale of an ambitious sea voyage spent mostly on dry land...The Island of author Stephen R. Bown's title figures only in the final stages of this expedition, also known as the Great Northern Expedition. His expansive book covers far more territory, though, ensuring readers understand the related history necessary to put both of these massive voyages in context."Washington Independent Review of Books

-

"The account is based on source materials, but reads like an adventure novel...Profiles of individual courage, scientific determination, and insights into the politics and struggles of expeditions create an engrossing history that's hard to put down."Donovan?s Bookshelf

-

"A moving account of how the great Kamchatka expedition morphed into a ten-year odyssey of hardship and conflict...A fine addition to the literature of Arctic exploration."Natural History

-

"Island of the Blue Foxes moves quickly, and [Stephen] Bown does a fine job of giving readers a strong feel for both what the men endured and how the personal characters of the major players were tested by their tribulations...A must-read."Anchorage Daily News

-

"A focused, interesting summary...The book ends with an adroit summing up of the post-expedition history of events that Bering's voyages set in motion, which had huge consequences for the wildlife and peoples native to Alaska and its eventual acquisition by the US...Recommended."Choice

-

"Tells the fascinating story of Danish explorer Vitus Bering's overly ambitious and ultimately doomed scientific expedition."Military Officer

-

"This makes Bown's third book that might be found in the frozen-food section, and his best yet...This tale twists over an uncharted early eighteenth-century world where ship-wreck often spells certain doom. However, in this case, the sea gives up her dead to return and tell the living of the lessons learned."Seattle Book Review

-

"Nearly every story of Arctic and Antarctic exploration is fraught with tragedy, privation and death. However, Bown's expert account in The Island of the Blue Foxes is a particularly grisly tale...Bown's other books include the excellent The Last Viking: The Life of Roald Amundsen, the greatest polar explorer of all time. He was first to the South Pole and among the earliest to the North Pole. Who better than Bown to write about the Great Northern Expedition?"Internet Review of Books

-

"This book will appeal to a general readership, but also to students of Arctic history and specialist Arctic historians."Arctic Journal

-

"A riveting account of two expeditions...Various characters come alive in the book...But the ultimate character in the story is Russia itself and its dark colonial past."Down to Earth

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use