Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

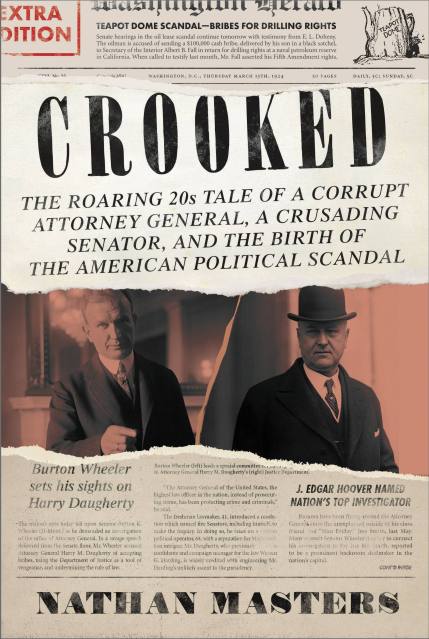

Crooked

The Roaring '20s Tale of a Corrupt Attorney General, a Crusading Senator, and the Birth of the American Political Scandal

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 21, 2023

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306826139

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 21, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Many tales from the Jazz Age reek of crime and corruption. But perhaps the era’s greatest political fiasco—one that resulted in a nationwide scandal, a public reckoning at the Department of Justice, the rise of J. Edgar Hoover, and an Oscar-winning film—has long been lost to the annals of history. In Crooked, Nathan Masters restores this story of murderers, con artists, secret lovers, spies, bootleggers, and corrupt politicians to its full, page-turning glory.

Newly elected to the Senate on a promise to root out corruption, Burton “Boxcar Burt” Wheeler sets his sights on ousting Attorney General Harry Daugherty, puppet-master behind President Harding’s unlikely rise to power. Daugherty is famous for doing whatever it takes to keep his boss in power, and his cozy relations with bootleggers and other scofflaws have long spawned rumors of impropriety. But when his constant companion and trusted fixer, Jess Smith, is found dead of a gunshot wound in the apartment the two men share, Daugherty is suddenly thrust into the spotlight, exposing the rot consuming the Harding administration to a shocked public.

Determined to uncover the truth in the ensuing investigation, Wheeler takes the prosecutorial reins and subpoenas a rogue’s gallery of witnesses—convicted felons, shady detectives, disgraced officials—to expose the attorney general’s treachery and solve the riddle of Jess Smith’s suspicious death. With the muckraking senator hot on his trail, Daugherty turns to his greatest weapon, the nascent Federal Bureau of Investigation, whose eager second-in-command, J. Edgar Hoover, sees opportunity amidst the chaos.

Packed with political intrigue, salacious scandal, and no shortage of lessons for our modern era of political discord, Nathan Masters’ thrilling historical narrative shows how this intricate web of inconceivable crookedness set the stage for the next century of American political scandals.

-

"In Crooked, Nathan Masters weaves together a sordid story of deep and pervasive rot at the Department of Justice... In Mr. Masters’s telling, the investigation has all the makings of a great film plot, complete with theatrical witnesses, twists, turns and a conclusive, if slightly maddening ending."Wall Street Journal

-

“An enlightening look at American political scandals in the 1920s, which continue to shape how politics is played to this day.”Star Tribune

-

“Masters makes an impressive book debut with a brisk, lively history of a political scandal, ‘one of those Roaring Twenties spectacles…that held the entire nation spellbound.’…Drawing on extensive archival research, [he] creates a tense narrative peopled by colorful, often unsavory characters…A stirring look at a shameful episode that holds distressing relevance for today.”Kirkus

-

“Although the events took place many decades ago, the story is as timely now as it ever was, and Masters brings it to pulsing life. Wheeler, Daugherty, and the various supporting players (including J. Edgar Hoover, before the world knew who he was) emerge as fully fleshed-out people, and the story is as exciting as any political thriller.”Booklist

-

“CROOKED is the fascinating tale about how a freshman senator from Montana took down one of the most corrupt and powerful Attorney Generals in US history. The fight between Senator ‘Boxcar Burt’ Wheeler and Attorney General Harry Daugherty led to the principles underlying the Department of Justice and the role of congressional oversight that we rely upon today. Filled with a cast of colorful characters and crimes and scandals galore, CROOKED is narrative history at its best.”Janet Napolitano, former Secretary of Homeland Security and US Attorney for Arizona

-

“Readers should be forgiven if they find CROOKED, Nathan Masters’s riveting account of a wild political scandal, too fantastic a story to be true. Yet it is true, and filled with the sort of amusing absurdities and eccentric characters—savvy bootleggers, scheming detectives, con artists, spies, and unscrupulous and opportunistic officials—that could only have occurred and existed during the Roaring Twenties. CROOKED depicts this fascinating era (with its many uncanny modern-day parallels) with such precision and verve that I couldn’t put it down.”Abbott Kahler, New York Times bestselling author (as Karen Abbott) of The Ghosts of Eden Park

-

“Nathan Masters delivers a powerful and thrilling nonfiction debut, packed with larger-than-life government officials and scheming operatives. Through groundbreaking research and sparkling prose, CROOKED unveils a page-turning origin story of political scandal.”Matthew Pearl, New York Times bestselling author of The Dante Club and The Taking of Jemima Boone

-

"Nathan Masters' deeply researched tale of Teapot Dome, the presidential scandal that would define political scandal for fifty years, is filled with strange, colorful characters and puts the reader right in the middle of one of the wildest stories in American political history."Garrett M. Graff, New York Times bestselling author of Watergate: A New History

-

"Nathan Masters' CROOKED unfolds like a gripping mystery novel, only the plot and characters are real and the power struggles reach the top levels of Washington's power elite. A Senate investigation that riveted the country, accusations of corruption in the justice department, a politically-convenient suicide in which the facts don't add up, the country's greatest detective, a red-haired key witness named RoxieB>this story is missing nothing. It's also an important story about our nation's past and about the workings of government. Well done, Mr. Masters."A.J. Baime, New York Times bestselling author of The Accidental President

-

“'An impressive debut ... Masters’ genius for character- and action-driven storytelling breathes life into a century-old political scandal that resonates today.”Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine