By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

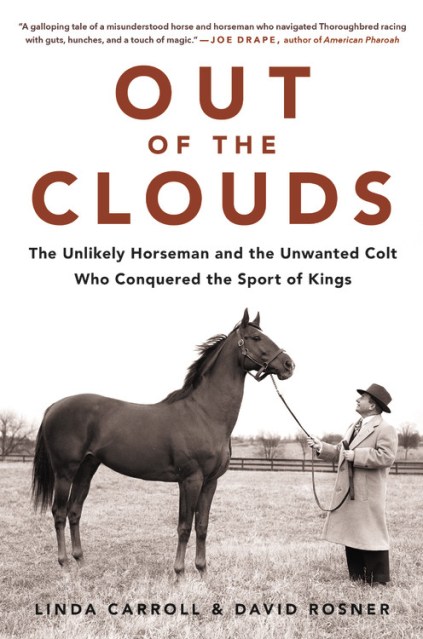

Out of the Clouds

The Unlikely Horseman and the Unwanted Colt Who Conquered the Sport of Kings

Contributors

By David Rosner

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 29, 2018

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316432238

Price

$37.00Price

$48.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $37.00 $48.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 29, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In the wake of World War II, as turmoil and chaos were giving way to a spirit of optimism, Americans were looking for inspiration and role models showing that it was possible to start from the bottom and work your way up to the top-and they found it in Stymie, the failed racehorse plucked from the discard heap by trainer Hirsch Jacobs. Like Stymie, Jacobs was a commoner in “The Sport of Kings,” a dirt-poor Brooklyn city slicker who forged an unlikely career as racing’s winningest trainer by buying cheap, unsound nags and magically transforming them into winners. The $1,500 pittance Jacobs paid to claim Stymie became history’s biggest bargain as the ultimate iron horse went on to run a whopping 131 races and win 25 stakes, becoming the first Thoroughbred ever to earn more than $900,000. The Cinderella champion nicknamed “The People’s Horse” captivated the masses with his rousing charge-from-behind stretch runs, his gritty blue-collar work ethic, and his rags-to-riches success story. In a golden age when horse racing rivaled baseball and boxing as America’s most popular pastime, he was every bit as inspiring a sports hero as Joe DiMaggio and Joe Louis.

Taking readers on a crowd-pleasing ride with Stymie and Jacobs, Out of the Clouds — the winner of the Dr. Tony Ryan Book Award — unwinds a real-life Horatio Alger tale of a dauntless team and its working-class fans who lived vicariously through the stouthearted little colt they embraced as their own.

-

"Out of the Clouds is more than the story of a single horse, a single trainer, and their unlikely rise. The whole mid-century world of grit and cigars, of prize fights and thick New York accents--guys and dolls--is in these pages. The book is as much about the big picture as it is the close-up."The Wall Street Journal

-

"The best racetrack books make you fall in love with a horse and become enthralled with the people around him, and that's exactly what Out of the Clouds does. It's a galloping tale of a misunderstood horse and horseman who navigated thoroughbred racing with guts, hunches, and a touch of magic."Joe Drape, New York Times bestselling author of AmericanPharoah: The Untold Story of the Triple Crown Winner's Legendary Rise

-

"I was stunned and pleased by Out of the Clouds... an engaging story of a man's life, his nature, his wisdom, and the prolonged success born of talent, dedication, and compassion."Edward L. Bowen, former editor-in-chief of TheBlood-Horse and author of author of 20 books onThoroughbred racing

-

"Two of Thoroughbred racing's greatest rags-to-riches stories--chronicling the rise of trainer Hirsch Jacobs and his champion, Stymie, from the lowest rungs of the sport to its loftiest peak, the Racing Hall of Fame--are here woven together in a tale further inhabited and enriched by some of racing's most legendary gamblers and characters, from high-rolling Arnold Rothstein to journalist Damon Runyon. Out of the Clouds is a colorful, engaging account of their racetrack world."William Nack, bestselling author of Secretariat

-

"A sensational book...When it comes to history and colorful characters, Out of the Clouds is right up there with Seabiscuit, and is as riveting a racing/history book from start to finish as I have ever read."Steve Haskin, The Blood-Horse

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use