By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

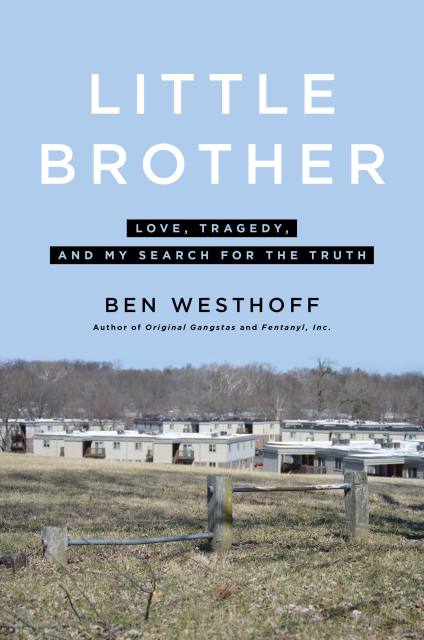

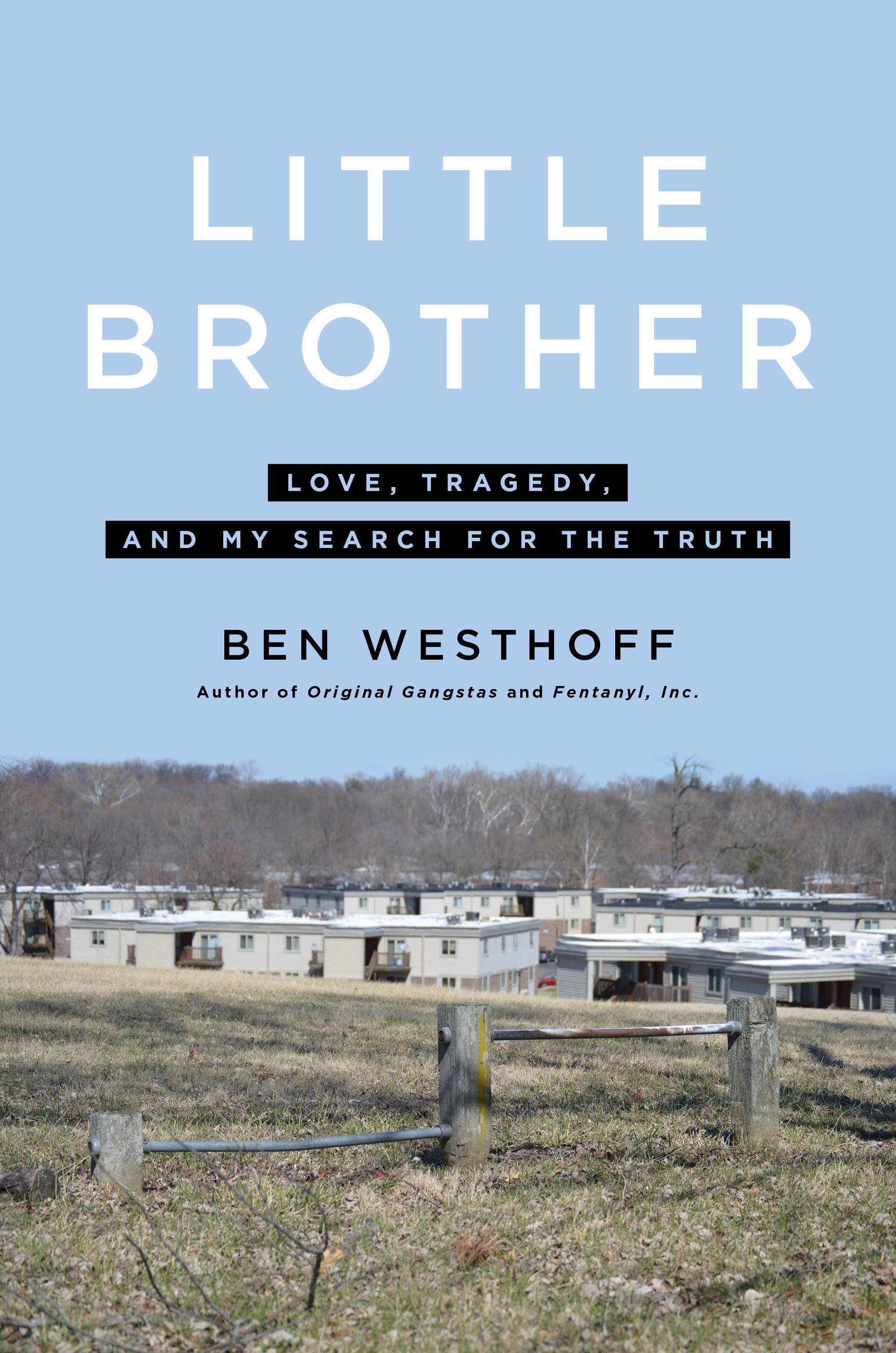

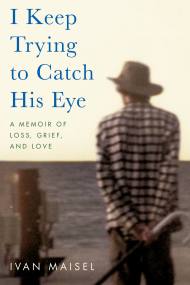

Little Brother

Love, Tragedy, and My Search for the Truth

Contributors

By Ben Westhoff

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 24, 2022

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306923173

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 24, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This intimate exploration of race and inequality in America tells the story of a journalist’s long-time relationship with his mentee, Jorell Cleveland, through the Big Brothers Big Sisters program and investigates Jorell’s tragic fatal shooting.

In 2005, soon after Ben Westhoff moved to St. Louis, he joined the Big Brothers Big Sisters program and was paired with Jorell Cleveland. Ben was twenty-eight, a white college grad from an affluent family. Jorell was eight, one of nine children from a poor, African American family living in nearby Ferguson. But the two instantly connected. Ben and Jorell formed a bond stronger than nearly any other in their lives. When Ben met the woman who’d become his wife, she observed that Ben and Jorell were “a package deal.” They were brothers.In the summer of 2016, Jorell was shot at point blank range in broad daylight in the middle of the street, yet no one was charged in his death. Ben grappled with mourning Jorell, but also with a feeling of responsibility. As Jorell’s mentor, what could he have done differently? As a journalist, he had reported on gang life, interviewed crime kingpins, and even infiltrated drug labs in China. But now, he was investigating the life and death of someone he knew personally and examining what he did and did not know about his friend. Learning the truth about Jorell and the man who killed him required Ben to uncover a heartbreaking cycle of poverty, poor education, drug trafficking, and violence. Little Brother brilliantly combines a deeply personal history with a true-crime narrative that exposes the realities of life in communities like Ferguson all around the country.

-

An A-List Editor's Choice selection from St. Louis Magazine

-

A St. Louis Post-Dispatch Top Nonfiction Book of 2022

-

"The creative and original telling of a young man’s life and death on the streets and the Big Brother who sought his killer.”Sam Quinones, author Dreamland

-

"Important and a must-read."Gerald Early, The Common Reader

-

“Westhoff’s new book, Little Brother: Love, Tragedy, and My Search for the Truth, is a memoir, a double bildungsroman, and a murder mystery. By combining these forms, it goes deeper than any one of them could…. The book opens a navigable passage between their separate worlds, and it goes below the surface characterizations, the stereotypes and assumptions that kill any honest discussion….Little Brother also makes a subtler point: that it is possible for two people to love each other across worldviews that do not sync. Jorell’s life is as exhausting and dangerous as any double agent’s. The details Westhoff uncovered teach us about his home terrain, about the geopolitics of isolation, about realpolitik and the limitations of allies.“If a reporter had parachuted into this story, it would have ended up a flat, remote, predictable account of one more young Black man’s death. But because Westhoff lived it, because he cared, he lets us wonder and puzzle and rage along with him.”The Los Angeles Review of Books

-

"I finished Little Brother in one day. It humanizes people and communities who have long been dehumanized. So much of it hits close to home. Ben Westhoff has taken a lot of crazy risks in his work before, but it’s the emotional exploration here that makes it his bravest work yet.”Aisha Sultan, St. Louis Post-Dispatch columnist

-

"Briskly paced...gritty,...[and] personal."New York Journal of Books

-

"With Little Brother, Ben Westhoff takes a relentless journalistic approach to discovering truths about a personal tragedy. Masterful."Toriano Porter, Kansas City Star editorial board member and author of The Pride of Park Avenue

-

“Meaningful memoir…Author and journalist Ben Westhoff’s investigation into the murder of his Big Brothers Big Sisters mentee, Jorell Cleveland, is not only a deeply personal, emotional memoir, but it’s also one of the best examinations of the systemic issues that lead to the deaths of so many young men in North County.”St. Louis Magazine

-

"A very good narrative by a very good author."Tyler Cowen, economist

-

“Thought-provoking…[an] ultimately satisfying study in true crime.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“The death of a young Black man begets a thought-provoking…account from journalist [Ben] Westhoff…showcasing his investigative chops."Publishers Weekly

-

“Westhoff’s...most personal book yet explores the multilayered communal aspects of grief, justice, and loss as he investigates the murder of Jorell Cleveland…. A heartfelt account of a life cut short, and the jarring inequities that contributed to the tragedy."Library Journal

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use