Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

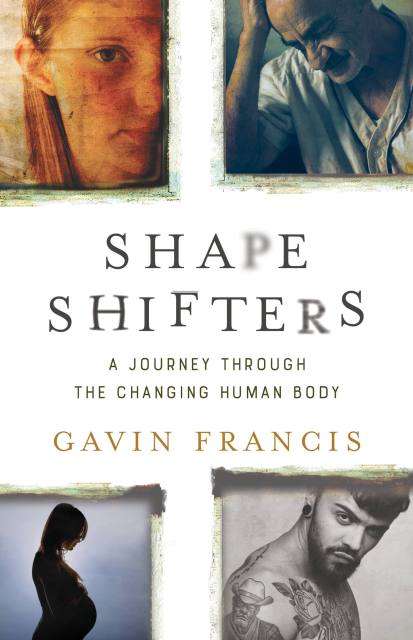

Shapeshifters

A Journey Through the Changing Human Body

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 5, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

To be alive is to be in perpetual metamorphosis: growing, healing, learning, aging. In Shapeshifters, physician and writer Gavin Francis considers the inevitable changes all of our bodies undergo — such as birth, puberty, and death, but also laughter, sleeping, and healing-and those that only some of our bodies will: like getting a tattoo, experiencing psychosis, suffering anorexia, being pregnant, or undergoing a gender transition. In Francis’s hands, each event becomes an opportunity to explore the meaning of identity and the natures-biological, psychological, and philosophical-of our selves. True to its own subject, Shapeshifters combines Francis’s lyrical imagination and deep knowledge of medicine and the humanities for a life-altering read.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 5, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541697515

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use