By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

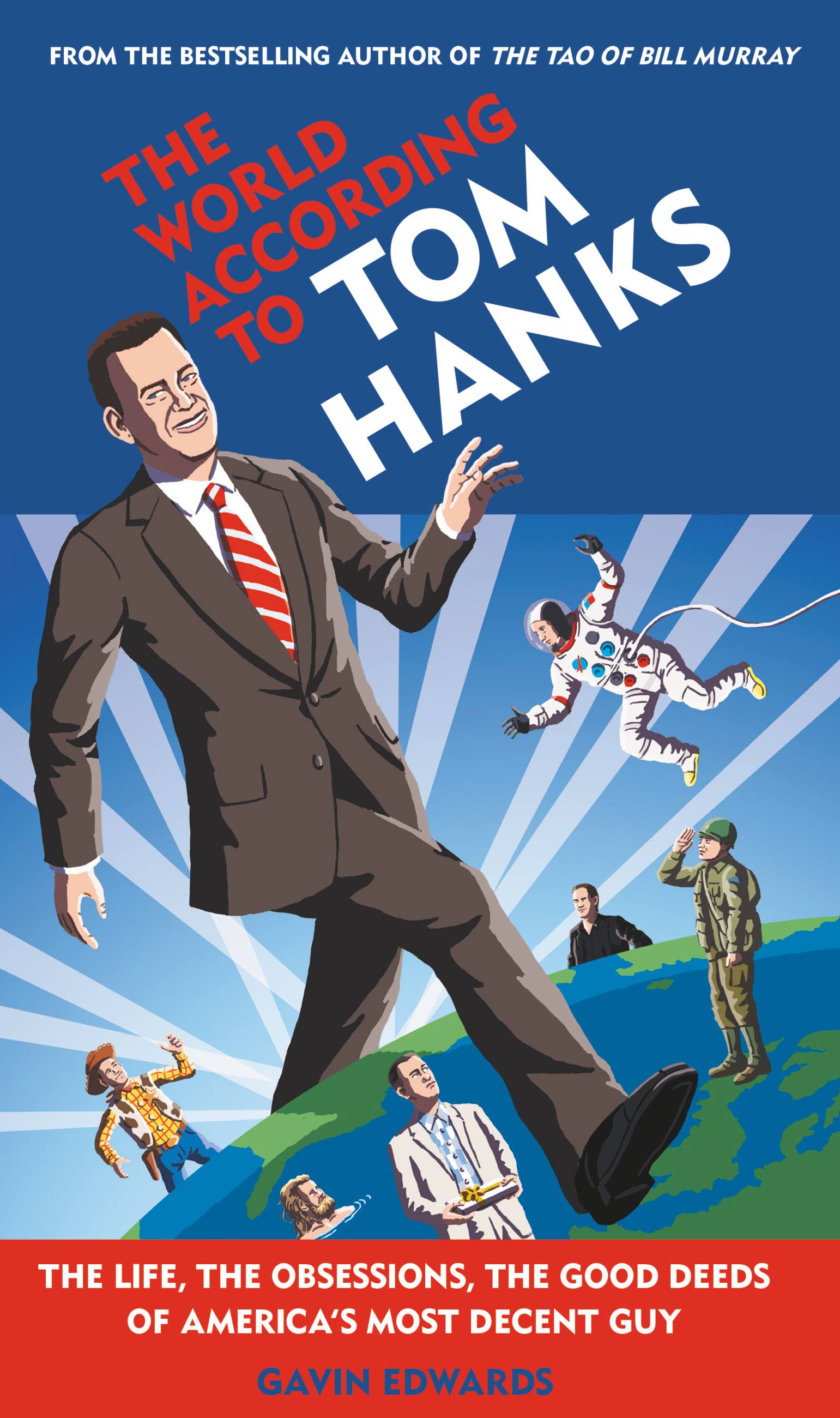

The World According to Tom Hanks

The Life, the Obsessions, the Good Deeds of America's Most Decent Guy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 23, 2018

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538712214

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $26.00 $33.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 23, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An entertaining and insightful homage to Tom Hanks, America’s favorite movie star, from the New York Times bestselling author of the cult sensation The Tao of Bill Murray.

Niceness gets a bad rap these days. Our culture rewards those who troll the hardest and who snark the most. At times it seems like there’s no place anymore for optimism, integrity, and good old-fashioned respect. Enter “America’s Dad”: Tom Hanks. Whether he’s buying espresso machines for the White House Press Corps, rewarding a jovial cab driver with a night out on Broadway, or extolling the virtues of using a typewriter, Hanks lives a passionate, joyful life and pays it forward to others. Gavin Edwards, the New York Times bestselling author of The Tao of Bill Murray, takes readers on a tour behind the scenes of Hanks’s life: from his less-than-idyllic childhood, rocky first marriage, and career wipeouts to the pinnacle of his acting career and domestic bliss with the love of his life, Rita Wilson.

As he did for Bill Murray, Edwards distills Hanks’s life story into ten “commandments” that beautifully encapsulate his All-American philosophy. Contemplating the life, the achievements, and the obsessions of Mr. Tom Hanks may or may not give you the road map you need to find your way. But at the very least, it’ll show you how niceness can be a worthy destination.

Niceness gets a bad rap these days. Our culture rewards those who troll the hardest and who snark the most. At times it seems like there’s no place anymore for optimism, integrity, and good old-fashioned respect. Enter “America’s Dad”: Tom Hanks. Whether he’s buying espresso machines for the White House Press Corps, rewarding a jovial cab driver with a night out on Broadway, or extolling the virtues of using a typewriter, Hanks lives a passionate, joyful life and pays it forward to others. Gavin Edwards, the New York Times bestselling author of The Tao of Bill Murray, takes readers on a tour behind the scenes of Hanks’s life: from his less-than-idyllic childhood, rocky first marriage, and career wipeouts to the pinnacle of his acting career and domestic bliss with the love of his life, Rita Wilson.

As he did for Bill Murray, Edwards distills Hanks’s life story into ten “commandments” that beautifully encapsulate his All-American philosophy. Contemplating the life, the achievements, and the obsessions of Mr. Tom Hanks may or may not give you the road map you need to find your way. But at the very least, it’ll show you how niceness can be a worthy destination.

-

"If there is a new Mr. Rogers in our culture, it's got to be Tom Hanks: honest, decent, trustworthy. Gavin Edwards's book taps into what makes Hanks someone we love and someone we should emulate."Morgan Neville, director of Won't You Be My Neighbor?

-

"There have been greater, weightier testaments to the art of cinema published in 2016 . . . but for sheer dopamine release, [The Tao of Bill Murray is] hard to beat."The New York Times Book Review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use