By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

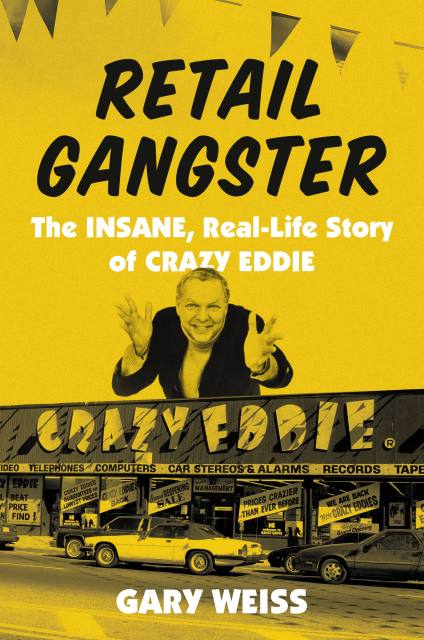

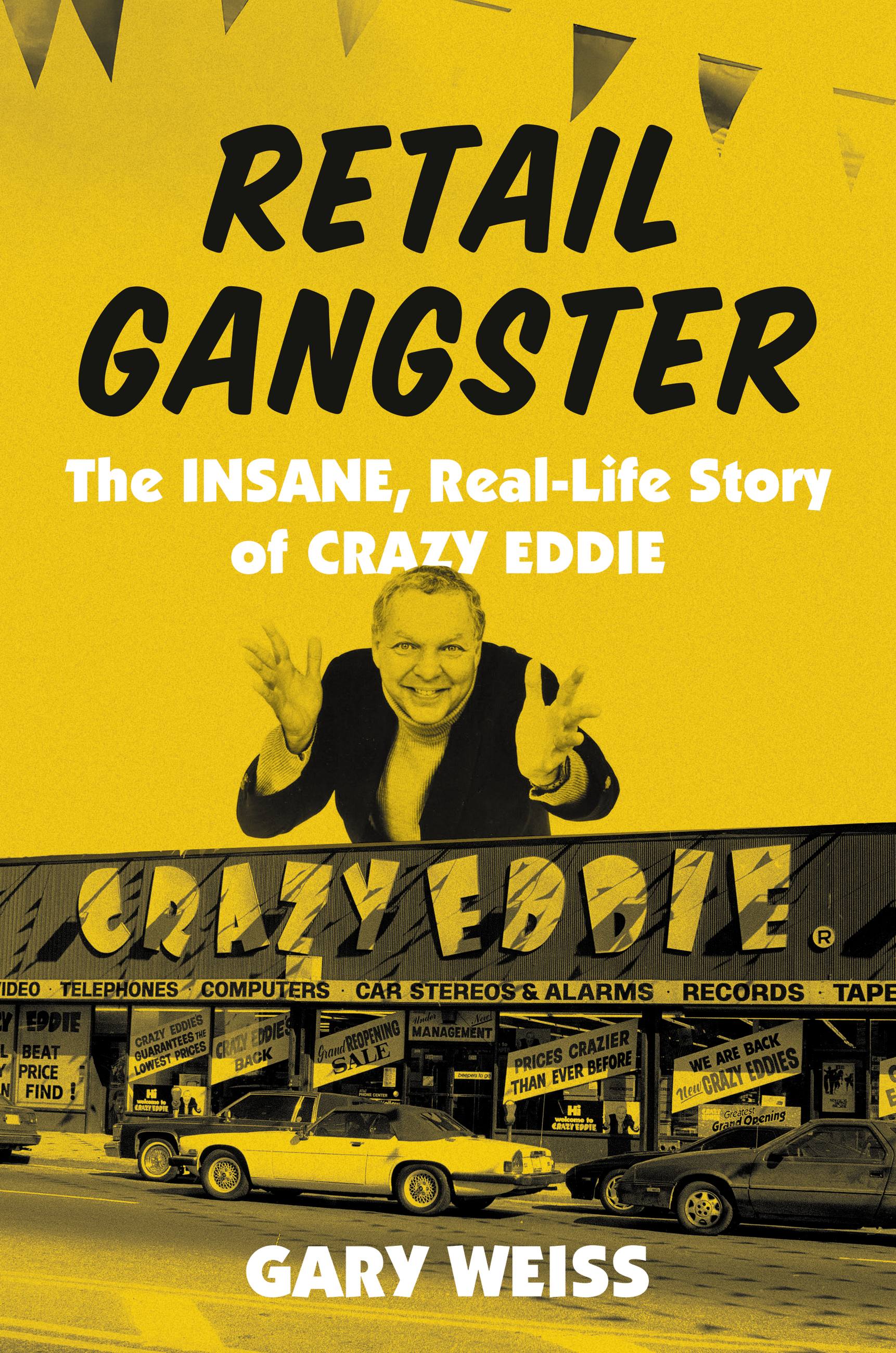

Retail Gangster

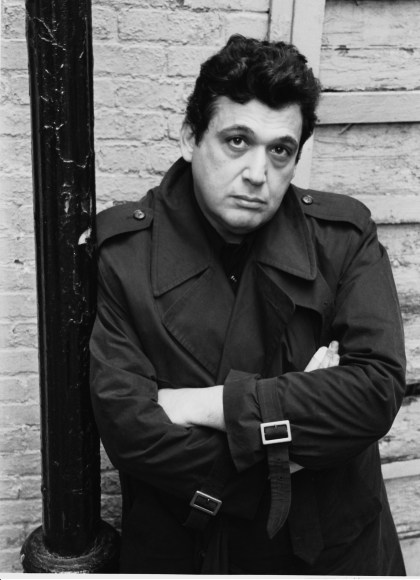

The Insane, Real-Life Story of Crazy Eddie

Contributors

By Gary Weiss

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 23, 2022

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306924569

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 23, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Back in the fall of 2016 we heard the news about the passing of Eddie Antar, "Crazy Eddie" as he was known to millions of people, the man behind the successful chain of electronic stores and one of the most iconic ad campaigns in history. Few things evoke the New York of a particular era the way "Crazy Eddie! His prices are insaaaaane!" does. The journalist Herb Greenberg called his death the "end of an era" and that couldn't be more true. What's insane is that his story has never been told.

Before Enron, before Madoff, before The Wolf of Wall Street, Eddie Antar's corruption was second to none. The difference was that it was a street franchise, a local place that was in the blood stream of everyone's daily life in the 1970s and early '80s. And Eddie pulled it off with a certain style, an in your face blue collar chutzpah. Despite the fact that then U.S. Attorney Michael Chertoffcalled him "the Darth Vader of capitalism" after the extent of the fraud was revealed, one of the largest SEC frauds in American history after Crazy Eddie's stores went public in 1984, Eddie was talked about fondly by the people who worked for him. They still do–there are myriads of ex-Crazy Eddie employee web pages that still attract fans, and the Crazy Eddie fraud scheme is now taught in every business school across the United States.

Many years have passed since the franchise went down in spectacular fashion but Crazy Eddie's moment has endured the way that iconic brands and characters do–one only need Google the media outpouring that accompanied his death. Maybe it's because it crystallized everything about 1970s New York almost perfectly, the merchandise and rise of consumer electronics (stereos!), the ads (cheesy!), the money (cash!). In Retail Gangster, investigative journalist Gary Weiss takes readers behind the scenes of one of the most unbelievable business scam stories of all time, a story spanning continents and generations, reaffirming the old adage that the truth is often stranger than fiction.

Genre:

-

**A New York Times Book Review Editor's Choice!**

**Washington Post, "10 Best Audiobooks of 2022"**

Book Riot, "16 Mystery, Thriller, True Crime Books to Read" (August 2022)

Philadelphia Inquirer, "The best new books to read in September"

Washington Post, "3 Best Audiobooks to Listen To This Month" (October 2022)

Urban Daddy, "Holiday Gift Guide" (2022)

-

"A compact and appealing account of Crazy Eddie’s artificially inflated rise and slow-mo collapse… Subcutaneously, Retail Gangster is a tender requiem for a time [past] … But the meat of this limber book is its investigation into the deep family drama and funny money behind Crazy Eddie.”New York Times

-

"Highbrow brilliant."New York Magazine

-

"[A] fast-paced, entertaining narrative… Mr. Weiss is an enthusiastic storyteller, and he does a terrific job synthesizing a dizzying amount of information.”Wall Street Journal

-

"Weiss’s irresistible account of the life of Eddie Antar, a small-time huckster and high school dropout who became a wealthy merchant, securities fraudster, fugitive and convict, is also a tale of the rise of consumer electronics in America and a fond portrait of the sleazy, disintegrating city that was New York in the 1970s."Washington Post

-

"A must-read... Weiss deftly weaves the family story, with the New York Zeitgeist of the 1970s and 1980s, along with the rather complicated frauds committed by the Sam and Eddie Antar. In other words, he turns the complicated and baffling into simple and understandable. This book is worth your time, and Weiss should be saluted for his work."Forbes

-

"It's a very good and highly entertaining book, and a very good reminder that the scammers we know now in the startup world have plenty of history to call their own."NPR's "Pop Culture Happy Hour"

-

“A rollicking chronicle of malignity, criminality, and family intrigue. The book not only documents Antar’s nefarious antics in lucid detail. It also evokes the saga of the Syrian Jews who fled the depredations of their Turkish overlords for the promised land of America in the early 20th century and prospered, mostly honestly, beyond their dreams.”Commentary

-

"Wonderfully told."Crain's New York Business

-

"Extraordinary."Philadelphia Inquirer

-

"It’s a rare business book from which you learn about an important industry and the methods of a criminal enterprise, all while shaking with laughter at the human beings involved as they attempt to rip off everyone in sight from customers to insurance companies to their own family members... Weiss writes up this tale of crime and punishment with great New York verve, delivering a probing examination of a profane way of doing business."Washington Free Beacon

-

"...Weiss brings his own gifts--a penchant for exhaustive research and a remarkably straightforward style--to bear upon a very complicated and twisty tale."Federal Lawyer

-

“Weiss paints an intricate portrait of greed, aspiration, and complicated family ties… A compellingly readable story about a con artist who 'epitomized the duality of the American Dream.'"Kirkus

-

“Crazy Eddie was one of the most brazen, longest-running frauds in history. For twenty years, the criminal mastermind Eddie Antar fooled everyone he came into contact with, from Wall Street 'masters of the universe' to the government, the media and the people who came into his stores. Eddie went no higher than junior high school—the first of his many crimes was truancy—but that did not hamper him. He was as brilliant as he was dishonest. As detailed in this enthralling book, Crazy Eddie was a merchandising phenomenon as well as a world-class con game. Eddie might have been a successful businessman had he not sought the American Dream through crime.Frank W. Abagnale Jr., New York Times bestselling author of Catch Me if You Can

Retail Gangster ties together all the strands of the Crazy Eddie story in an immensely readable and enjoyable narrative, filled with fascinating characters, astounding subplots, and more plot twists than a pretzel.”

-

“Eddie Antar, what a shtarker! Whew! It’s so strange to me that I am even peripherally a part of the story of Crazy Eddie! How can this be?! I wonder who it was that saw my Zap Comix cover and suggested using it for their logo.Robert Crumb, cartoonist, creator of Fritz the Cat and Keep on Truckin'

“Gary Weiss has done the world a service in having taken pains to lay out in all its sleazy detail the myriad ways that these guys conned everyone — the customers, the government, even Wall Street, even each other! Wow! And Weiss did it with humor. I occasionally found myself laughing, as when reading ‘churning out so much bogus paperwork required dishonesty on an industrial scale.’ The shenanigans are often described in this whimsical manner, which, while revealing bad behavior, is easier on the reader than if Weiss had used an indignant, outraged tone. You know, the absurd tragic comedy of it all, of gross human behavior, the layers of chicanery, the relentless lying and deceiving, the elaborate deceptions Weiss describes. The details are all of interest, and the effect is cumulative. Anyway, me, I want to know it all.

The question arises, how commonplace is such behavior in the business world, in big corporations, in banking and finance, in government agencies? How exceptional, or how typical, is the Antar family? There’s no way to know, I guess, unless somebody does a dedicated, long-term investigation of a specific company or organization or agency. The stuff about investment analysts and 'investment relations' and all that was very informative. I mean, who knew? I had no idea, although, being a suspicious character by nature, I suspect them all of liking ‘the feeling of pulling the wool over the consumers’ eyes.' The average working-class person doesn’t stand a chance, the way things are set up, by evil geniuses like Eddie Antar. God help us. We need a frickin’ army of investigative journalists like Weiss.”

-

“I would say that Retail Gangster reads like a Grisham thriller, only no one could have invented the absurd characters that populated the carnival of chaos called Crazy Eddie. Alternately hilarious, unbelievable and jaw-dropping, Gary Weiss’s superb book explores the shifting boundaries of truth and lies, love and betrayal. Between depictions of vicious family drama, pathological greed, and massive fraud, it lays bare the worst of the go-go 1980s, exposing Wall Street analysts and executives as the handmaidens of this deception that wrecked untold numbers of investors. If you want to understand the types of financial dishonesty that will continue to haunt our markets long into the future, read this indispensable history of Eddie Antar and his unbelievable family.”Kurt Eichenwald, award-winning journalist and New York Times bestselling author of The Informant, Conspiracy of Fools and A Mind Unraveled

-

“An absorbing and revealing treatise on the underbelly of the American Dream, where scam artists and businessmen are one and the same, and the fruits of their labor—in this case an iconic ad campaign once familiar to all New Yorkers—was the byproduct of criminal chutzpah and greed. Retail Gangster will turn you inside out and have you reading late into the night.”T.J. English, author of Dangerous Rhythms, Havana Nocturne, and The Savage City

-

“A hi-fidelity dive into the complex and contradictory world of a kid who rode the American dream from immigrant Brooklyn to the coveted throne of New York discount electronics—and then to prison. A deeply reported and sensitive snapshot of the retail legend known as ‘Crazy Eddie,’ and of the place that lifted him up and brought him down.”Matti Friedman, author of Who by Fire and The Aleppo Codex

-

"This would be a remarkable work of fiction, except this tale of one man’s audacious addiction to fraud is true. Retail Gangster is destined to go down as a classic in the annals of public-company fraud. With his history of tracking gangsters, there was nobody better to tell that story than Gary Weiss."Herb Greenberg, veteran financial journalist and commentator

-

“If you lived in NYC in the late-1970s you we’re driven mad by Crazy Eddie commercials. But you shopped there just to see if he put his money where his big mouth was. You also wondered about the real Brooklyn guy behind the hype. In RETAIL GANGSTER, Gary Weiss takes you behind the ads and the loud dazzle into the truly insane life of Eddie Antar and with brilliant research, confident storytelling skills, and colorful anecdotes and a startling eye for the telling detail he takes us on a guided tour of audacious treachery and fraud that might have been the template for the Madoffs of the financial netherworld. You can’t stop reading this crazy tale because you keep thinking this can’t get anymore insane. And then it does. And what’s craziest of all is that it’s all true.”Denis Hamill, Ex-NY Daily News columnist, and author of Fork in the Road

-

“What a romp! With clarity and riveting detail, Weiss describes the rise and fall of a retail legend, and does it with the panache of Crazy Eddie himself—but without the lies. Rarely has accounting fraud been examined with such wit and energy. Add what may be the most insanely dysfunctional clan to ever operate a family business, and you have a thoroughly entertaining tale!”Diana B. Henriques, New York Times bestselling author of The Wizard of Lies and A First-Class Catastrophe

-

“Gary Weiss tackles the riveting saga of retailing huckster and shameless fraudster ‘Crazy Eddie’ with verve and panache. The result is a compelling yarn of a guy who embraced every crooked scheme he encountered, and snookered loyal employees, family, consumers and investors indiscriminately and with zero remorse. It's far more entertaining than any cautionary tale deserves to be!”Suzanne McGee, author of Chasing Goldman Sachs

-

“For those of us who lived in New York in the 1980s and 1990s, Crazy Eddie was part of the city’s unique DNA. I lived three blocks from the discount chain’s East 57th Street flagship store and it had a magnetic lure for all things electronic. I closely followed the news reports of the chain’s rise and fall. It was not until I read Gary Weiss’s extensively reported and wonderfully written Retail Gangster that I realized how little I knew. Relying on fresh interviews and new information he discovered in massive court filings, Weiss has delivered a page-turning tale that reveals the dysfunctional family saga behind one of the era’s most fabled criminal scams. The rags to riches story of the Antar family also provides a vivid and gripping account of the players in New York’s wild merger and acquisition frenzy and booming stock market. Weiss delivers a real-life version of Succession meets Bernie Madoff.”Gerald Posner, award-winning journalist and author of Pharma

-

"If you aren’t familiar with the saga of Crazy Eddie, fix that immediately. Read this book!"Helaine Olen, Washington Post Opinions

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use