Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

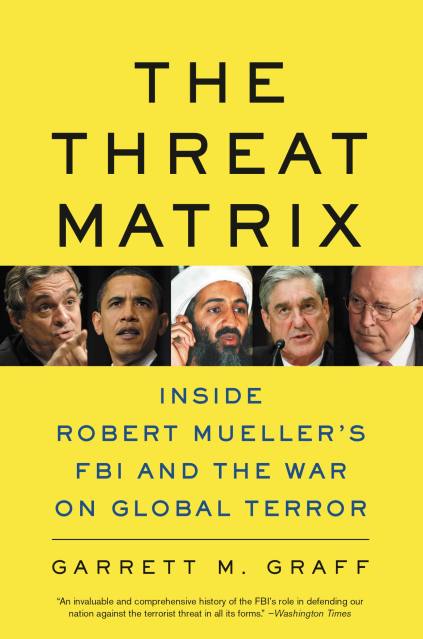

The Threat Matrix

Inside Robert Mueller's FBI and the War on Global Terror

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 28, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

An intimate look at Robert Mueller, the sixth Director of the FBI, who oversaw the investigation into ties between President Trump’s campaign and Russian officials.

Covering more than 30 years of history, from the 1980s through Obama’s presidency, The Threat Matrix explores the transformation of the FBI from a domestic law enforcement agency, handling bank robberies and local crimes, into an international intelligence agency — with more than 500 agents operating in more than 60 countries overseas — fighting extremist terrorism, cyber crimes, and, for the first time, American suicide bombers.

Based on access to never-before-seen task forces and FBI bases from Budapest, Hungary, to Quantico, Virginia, this book profiles the visionary agents who risked their lives to bring down criminals and terrorists both here in the U.S. and thousands of miles away long before the rest of the country was paying attention to terrorism. Given unprecedented access, thousands of pages of once secret documents, and hundreds of interviews, Garrett M. Graff takes us inside the FBI and its attempt to protect America from the Munich Olympics in 1972 to the attempted Times Square bombing in 2010. It also tells the inside story of the FBI’s behind-the-scenes fights with the CIA, the Department of Justice, and five White Houses over how to combat terrorism, balance civil liberties, and preserve security. The book also offers a never-before-seen intimate look at FBI Director Robert Mueller, the most important director since Hoover himself.

Brilliantly reported and suspensefully told, The Threat Matrix peers into the darkest corners of this secret war and will change your view of the FBI forever.

Covering more than 30 years of history, from the 1980s through Obama’s presidency, The Threat Matrix explores the transformation of the FBI from a domestic law enforcement agency, handling bank robberies and local crimes, into an international intelligence agency — with more than 500 agents operating in more than 60 countries overseas — fighting extremist terrorism, cyber crimes, and, for the first time, American suicide bombers.

Based on access to never-before-seen task forces and FBI bases from Budapest, Hungary, to Quantico, Virginia, this book profiles the visionary agents who risked their lives to bring down criminals and terrorists both here in the U.S. and thousands of miles away long before the rest of the country was paying attention to terrorism. Given unprecedented access, thousands of pages of once secret documents, and hundreds of interviews, Garrett M. Graff takes us inside the FBI and its attempt to protect America from the Munich Olympics in 1972 to the attempted Times Square bombing in 2010. It also tells the inside story of the FBI’s behind-the-scenes fights with the CIA, the Department of Justice, and five White Houses over how to combat terrorism, balance civil liberties, and preserve security. The book also offers a never-before-seen intimate look at FBI Director Robert Mueller, the most important director since Hoover himself.

Brilliantly reported and suspensefully told, The Threat Matrix peers into the darkest corners of this secret war and will change your view of the FBI forever.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 28, 2011

- Page Count

- 704 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316120883

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use