Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

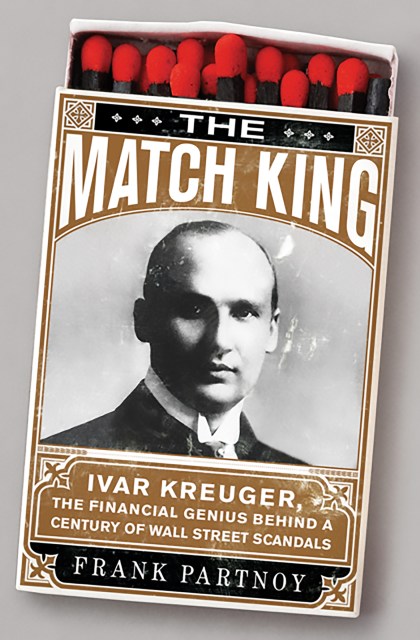

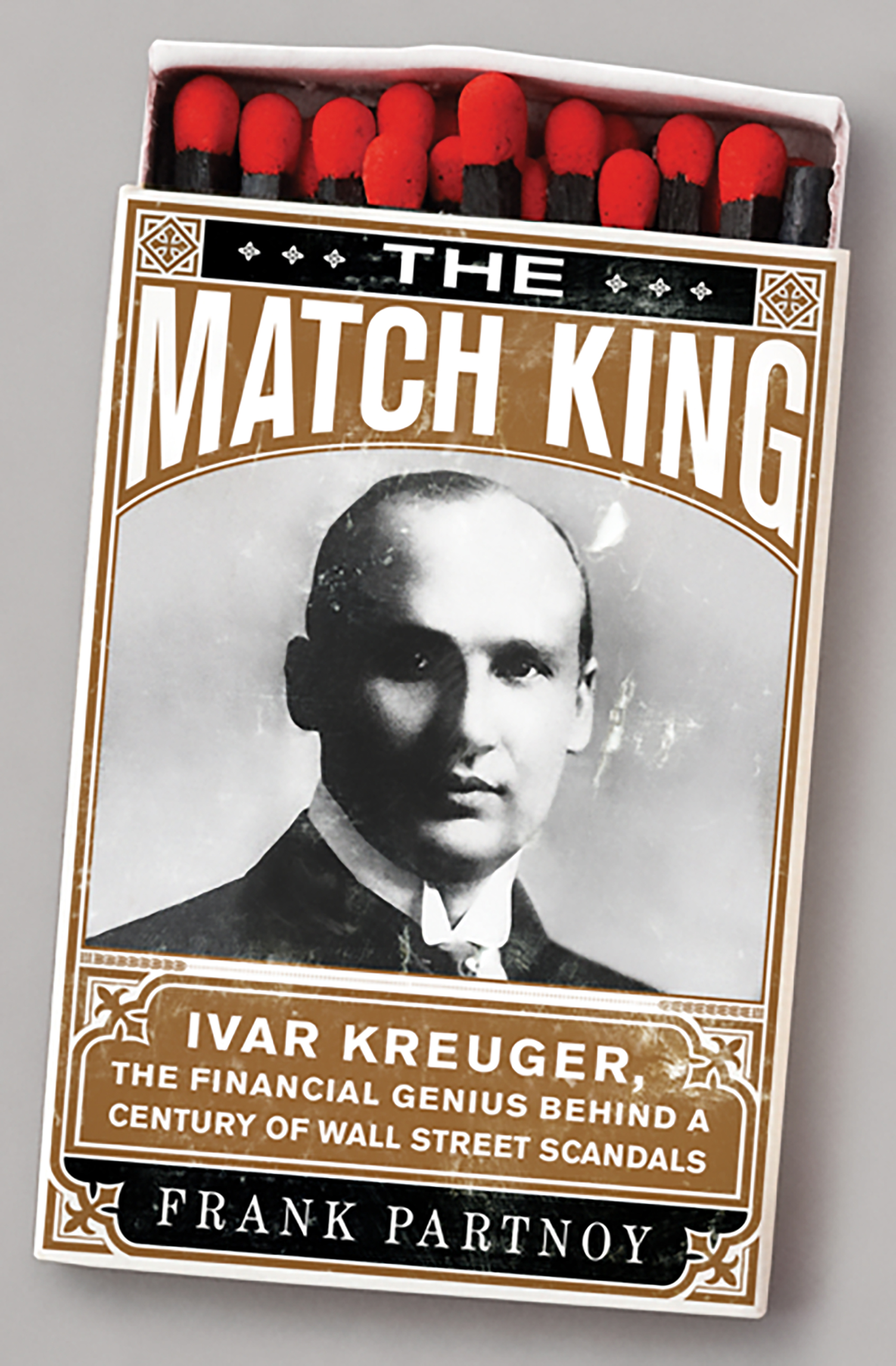

The Match King

Ivar Kreuger, The Financial Genius Behind a Century of Wall Street Scandals

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 9, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Yet after Kreuger’s suicide in 1932, the true nature of his empire emerged. Driven by success to adopt ever-more perilous practices, Kreuger had turned to shell companies in tax havens, fudged accounting figures, off-balance-sheet accounting, even forgery. He created a raft of innovative financial products — many of them precursors to instruments wreaking havoc in today’s markets. When his Wall Street empire collapsed, millions went bankrupt.

Frank Partnoy, a frequent commentator on financial disaster for the Financial Times, New York Times, NPR, and CBS’s “60 Minutes,” recasts the life story of a remarkable yet forgotten genius in ways that force us to re-think our ideas about the wisdom of crowds, the invisible hand, and the free and unfettered market.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 9, 2010

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786741540

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use