Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

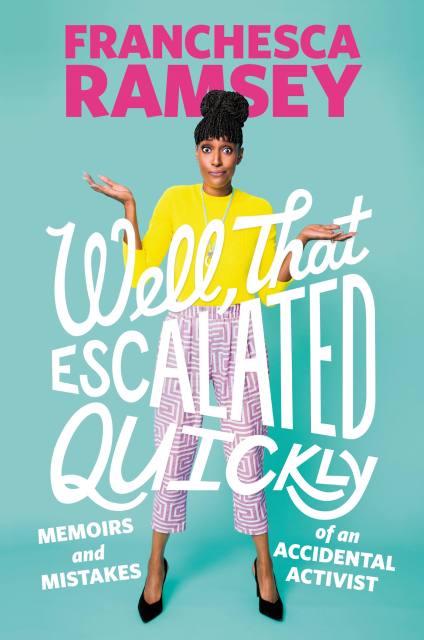

Well, That Escalated Quickly

Memoirs and Mistakes of an Accidental Activist

Contributors

Read by Franchesca Ramsey

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 22, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478999911

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $13.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 22, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Franchesca Ramsey didn’t set out to be an activist. Or a comedian. Or a commentator on identity, race, and culture, really. But then her YouTube video “What White Girls Say . . . to Black Girls” went viral. Twelve million views viral. Faced with an avalanche of media requests, fan letters, and hate mail, she had two choices: Jump in and make her voice heard or step back and let others frame the conversation. After a crash course in social justice and more than a few foot-in-mouth moments, she realized she had a unique talent and passion for breaking down injustice in America in ways that could make people listen and engage.

In her first book, Ramsey uses her own experiences as an accidental activist to explore the many ways we communicate with each other–from the highs of bridging gaps and making connections to the many pitfalls that accompany talking about race, power, sexuality, and gender in an unpredictable public space…the internet.

Well, that Escalated Quickly includes Ramsey’s advice on dealing with internet trolls and low-key racists, confessions about being a former online hater herself, and her personal hits and misses in activist debates with everyone from bigoted Facebook friends and misguided relatives to mainstream celebrities and YouTube influencers. With sharp humor and her trademark candor, Ramsey shows readers we can have tough conversations that move the dialogue forward, rather than backward, if we just approach them in the right way.