Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

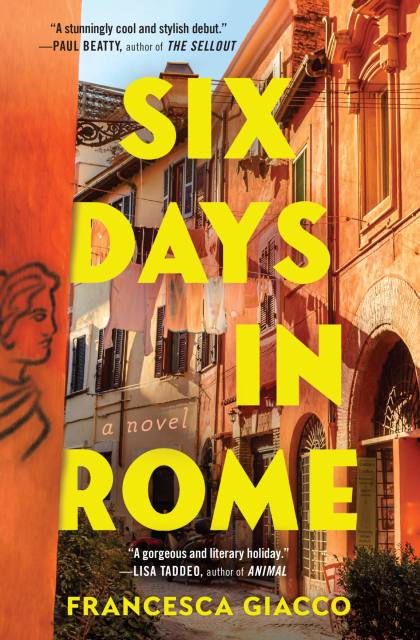

Six Days in Rome

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Emilia arrives in Rome reeling from heartbreak and reckoning with her past. What was supposed to be a romantic trip has, with the sudden end of a relationship, become a solitary one instead. As she wanders, music, art, food, and the beauty of Rome's wide piazzas and narrow streets color Emilia's dreamy, but weighty experience of the city. She considers the many facets of her life, drifting in and out of memory, following her train of thought wherever it leads.

While climbing a hill near Trastevere, she meets John, an American expat living a seemingly idyllic life. They are soon navigating an intriguing connection, one that brings pain they both hold into the light.

As their intimacy deepens, Emilia starts to see herself anew, both as a woman and as an artist. For the first time in her life, she confronts the ways in which she's been letting her father’s success as a musician overshadow her own. Forced to reckon with both her origins and the choices she's made, Emilia finds herself on a singular journey—and transformed in ways she never expected.

Equal parts visceral and cerebral, Six Days in Rome is an ode to the Eternal City, a celebration of art and creativity, and a meditation on self-discovery.

Includes a Reading Group Guide.

Genre:

-

"Francesca Giacco is a stunning writer and Six Days in Rome is a brilliant transporting experience—a novel about belonging with heart and heat; a gorgeous and literary holiday."Lisa Taddeo, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Three Women and Animal

-

“Sometimes it takes a three-thousand-year-old city to feel brand new. Six Days in Rome unfolds with all the crisp wonderment of a two-star hotel map. Sensorial as hell, it acknowledges the major landmarks and thoroughfares, but knows you have to get lost in the invisible, the unrendered to find what you didn’t know you were looking for. An ode to funky wine labels, good taste, and true inspiration, Francesca Giacco has penned a stunningly cool and stylish debut.”Paul Beatty, Man Booker Prize winning author of The Sellout

-

"If Sally Rooney and Frances Mayes co-wrote a novel in an Airbnb near the Spanish Steps, it might read something like Six Days in Rome. Smart, keenly observed, and deeply felt, this is a book for anyone who's ever journeyed abroad to find themselves."David Ebershoff, New York Times bestselling author of The Danish Girl and The 19th Wife

-

"Giacco's debut is an intimate, entertaining, clear-eyed evocation of a disillusioned young female artist's coming of age amongst the ruins of Rome and like her heart-broken narrator, very good company."Elissa Schappell, Author of Blueprints for Building Better Girls

-

"Six Days in Rome is a masterful debut—a literary travelogue that maps both the internal and external, capturing the intimate fireworks of heartbreak and the endless question of identity, alongside the sumptuous backdrop of Rome. Francesca Giacco has written a novel as artful as it is affecting."Adrienne Brodeur, Author of Wild Game: My Mother, Her Lover and Me

-

"Giacco’s rendering of collecting pieces of a shattered heart is relatable and encouraging . . . But an even greater draw is the feeling that just under a week in Italy really is included in the cover price, through descriptions of pistachio gelato drowned in olive oil, jasmine snaking up a crumbled Roman column, and exchanging the deep love of a partner for the rough kiss of an espresso-drinking stranger."Glamour

-

“In this sensual novel of rage, heartbreak, and desire, a young artist named Emilia travels to Rome to reckon with the end of a relationship. When an encounter with an American expat sparks a new connection, Emilia begins to see herself in a new light—both as a woman and as an artist.”Harper's Bazaar

-

"Elegant . . . Upscale escapism."Kirkus

-

"Sensual and deliberately paced . . . Giacco revels in her setting, providing rich descriptions of the streets, food, and people Emilia encounters . . . Sumptuously written."Publishers Weekly

-

"Writing—and travel writing in particular—should transport a reader. Surprisingly few authors can successfully do it. Francesca Giacco pulls it off in her debut novel . . . Passion, exploration, and reflection [pair] with evocative descriptions of pasta, glorious wines, magnificent museums, and architectural wonders."Air Mail

-

"Part Eat Pray Love, part Heartburn, part family saga, Giacco’s debut novel takes readers on a luscious journey rich in description and emotional resonance . . . Readers will want to linger in this world created by a promising new writer."Booklist

-

"Makes just as much sense of the ancient city at the heart of the book as it does love and heartbreak . . . may inspire you to take a solo journey, even if it's only one of self-discovery."The List

-

"Francesca Giacco’s exceptional use of language in Six Days in Rome creates an immensely nuanced protagonist in Emilia . . . Sensational sensory descriptions capture what it feels like to experience Rome’s famous and off-the-beaten-path sights in the sultry July heat, as well as the city’s sounds, touch, smells, and particularly its tastes . . . Giacco’s prose keeps us turning the page . . . for the intimacy she creates between us and Emilia so that we become enraptured in her nuanced journey and, ultimately, deeply care about where she’s been … and where she might be going."Martha’s Vineyard Times

-

"[A] contemplative, quite moving account of a heartbroken young artist’s overseas trip."The Film Stage

- On Sale

- May 3, 2022

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538706442

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use