Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

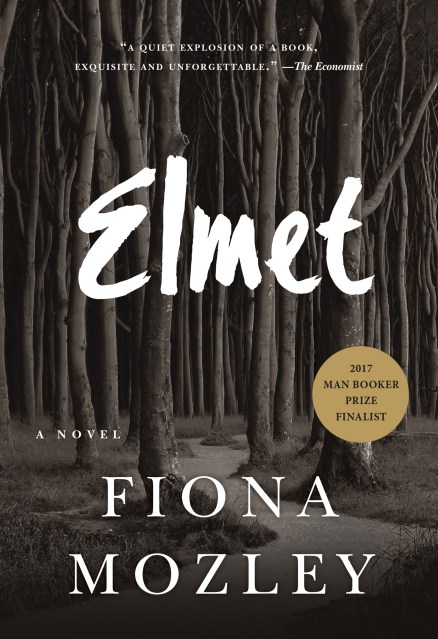

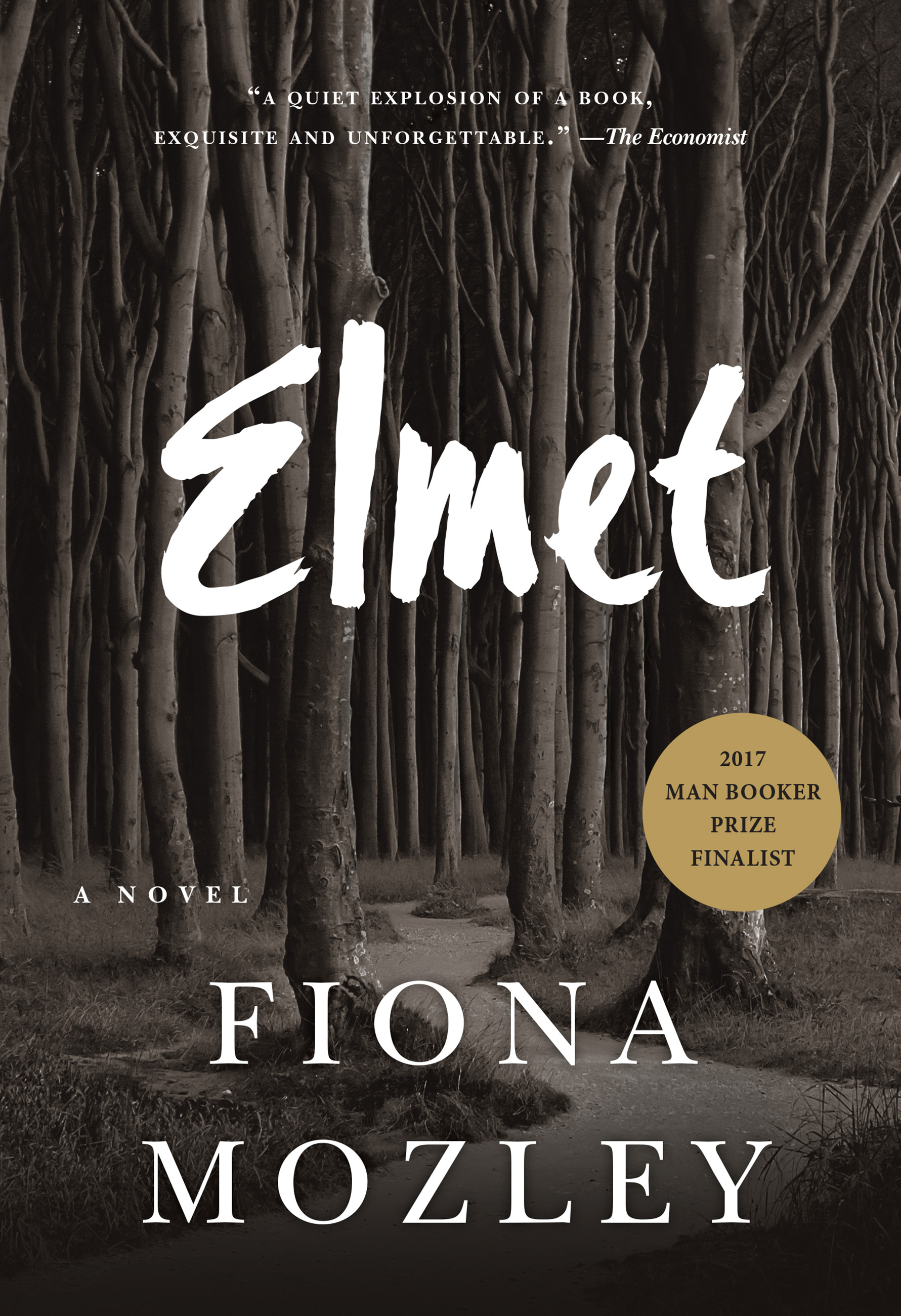

Elmet

Contributors

By Fiona Mozley

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Format

Format:

- ebook $10.99

- Trade Paperback $15.95 $21.95 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 5, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

FINALIST FOR THE 2017 MAN BOOKER PRIZE

**The Guardian Best Books of 2017 * December Indie Next Pick * Amazon Best of the Month * Amazon Debut Spotlight * PEOPLE Magazine BOOK OF THE WEEK**

“Beguiling . . . A lyrical and mythic work . . . Mozley’s sheer storytelling confidence sends the reader sailing.”

─New York Times

"A quiet explosion of a book, exquisite and unforgettable." —The Economist

"Part fairy tale, part coming-of-age story, part revenge tragedy with literary connections, Mozley's first novel is a shape-shifting, lyrical, but dark parable of life off the grid in modern Britain. Mozley's instantaneous success . . . is a response to the stylish intensity of her work, which boldly winds multiple genres into a rich spinning top of a tale."—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

The family thought the little house they had made themselves in Elmet, a corner of Yorkshire, was theirs, that their peaceful, self-sufficient life was safe. Cathy and Daniel roamed the woods freely, occasionally visiting a local woman for some schooling, living outside all conventions. Their father built things and hunted, working with his hands; sometimes he would disappear, forced to do secret, brutal work for money, but to them he was a gentle protector.

Narrated by Daniel after a catastrophic event has occurred, Elmet mesmerizes even as it becomes clear the family's solitary idyll will not last. When a local landowner shows up on their doorstep, their precarious existence is threatened, their innocence lost. Daddy and Cathy, both of them fierce, strong, and unyielding, set out to protect themselves and their neighbors, putting into motion a chain of events that can only end in violence.

As rich, wild, dark, and beautiful as its Yorkshire setting, Elmet is a gripping debut about life on the margins and the power—and limits—of family loyalty.

**The Guardian Best Books of 2017 * December Indie Next Pick * Amazon Best of the Month * Amazon Debut Spotlight * PEOPLE Magazine BOOK OF THE WEEK**

“Beguiling . . . A lyrical and mythic work . . . Mozley’s sheer storytelling confidence sends the reader sailing.”

─New York Times

"A quiet explosion of a book, exquisite and unforgettable." —The Economist

"Part fairy tale, part coming-of-age story, part revenge tragedy with literary connections, Mozley's first novel is a shape-shifting, lyrical, but dark parable of life off the grid in modern Britain. Mozley's instantaneous success . . . is a response to the stylish intensity of her work, which boldly winds multiple genres into a rich spinning top of a tale."—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

The family thought the little house they had made themselves in Elmet, a corner of Yorkshire, was theirs, that their peaceful, self-sufficient life was safe. Cathy and Daniel roamed the woods freely, occasionally visiting a local woman for some schooling, living outside all conventions. Their father built things and hunted, working with his hands; sometimes he would disappear, forced to do secret, brutal work for money, but to them he was a gentle protector.

Narrated by Daniel after a catastrophic event has occurred, Elmet mesmerizes even as it becomes clear the family's solitary idyll will not last. When a local landowner shows up on their doorstep, their precarious existence is threatened, their innocence lost. Daddy and Cathy, both of them fierce, strong, and unyielding, set out to protect themselves and their neighbors, putting into motion a chain of events that can only end in violence.

As rich, wild, dark, and beautiful as its Yorkshire setting, Elmet is a gripping debut about life on the margins and the power—and limits—of family loyalty.

Genre:

-

“Beguiling . . . A lyrical and mythic work . . . Mozley’s sheer storytelling confidence sends the reader sailing.”

─New York Times

“[A] magical debut novel. Set in modern-day Yorkshire, this dazzling debut feels steeped in a more primitive, violent past. Teenagers Cathy and Daniel are living self-sufficiently in the woods with their father—until their peaceful existence is threatened by a wealthy landowner. Narrated by 14-year-old Daniel in seductively poetic prose, the book shines a light on the toll of power wielded cruelly, as well as on a countering force: the extraordinary sustenance family devotion can provide.”

─People (Book of the Week)

“Shortlisted for the 2017 Man Booker Prize, Mozley’s preternaturally accomplished debut novel is a riveting and disquieting fable of a family reaching back to life’s essentials and embracing nature’s beauty, abundance, and challenges, yet remaining caught in the perpetual twist of human good and evil. In pristinely gorgeous and eviscerating prose, Mozley, who chimes with Hannah Tinti, Lydia Millet, and Daniel Woodrell, sets ablaze a suspenseful family tragedy stoked by social critique, escalated by men’s violence against women, and darkly veined with elements of country noir.”

─Booklist (starred review)

“Part fairy tale, part coming-of-age story, part revenge tragedy with literary connections, Mozley's first novel is a shape-shifting, lyrical, but dark parable of life off the grid in modern Britain. Mozley's instantaneous success . . . is a response to the stylish intensity of her work, which boldly winds multiple genres into a rich spinning top of a tale.”

─Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“Thrums with all the energy and life of the forests that surround the family . . . Rhythmic and lilting, the writing is dreamily poetic . . . Elmet is a rich and earthy tale of family life, sibling relationships, identity, how we define community.”

─Financial Times

“A quiet explosion of a book, exquisite and unforgettable.”

─The Economist

“An impressive slice of contemporary noir steeped in Yorkshire legend . . . Elmet possesses a rich and unfussy lyricism.”

─The Guardian

“A stunning debut…A wonder to behold. An utterly arresting novel about family, home, rural exploitation, violence and, most of all, the loyalty and love of children under siege.”

─Evening Standard (UK)

“[With] many eerily beautiful scenes . . . A rugged, potent work whose concentrated mixture of lyricism and violence recalls Cormac McCarthy.”

—Publishers Weekly

- On Sale

- Dec 5, 2017

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781616208448

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use