By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Iwigara

American Indian Ethnobotanical Traditions and Science

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 15, 2020

- Page Count

- 248 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781604698800

Price

$35.00Price

$46.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $46.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 15, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“A beautiful catalogue of 80 plants, revered by indigenous people for their nourishing, healing, and symbolic properties.” —Gardens Illustrated

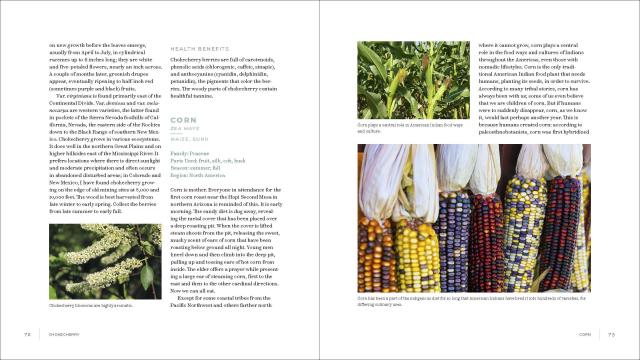

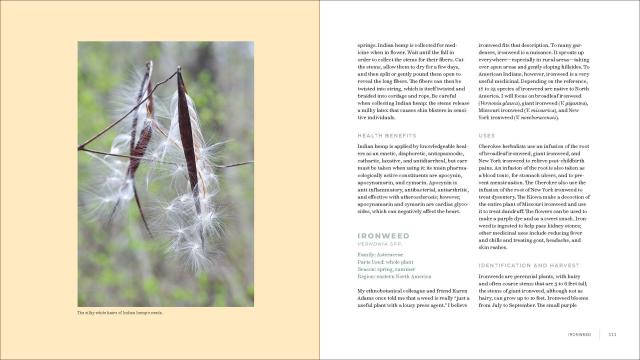

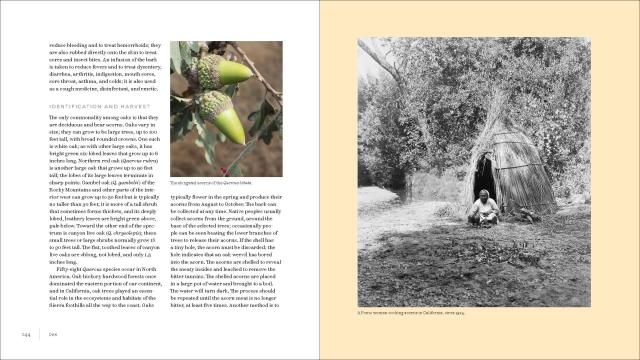

The belief that all life-forms are interconnected and share the same breath—known in the Rarámuri tribe as iwígara—has resulted in a treasury of knowledge about the natural world, passed down for millennia by native cultures. Ethnobotanist Enrique Salmón builds on this concept of connection and highlights plants revered by North America’s indigenous peoples.

Salmón teaches us the ways plants are used as food and medicine, the details of their identification and harvest, their important health benefits, plus their role in traditional stories and myths. Discover in these pages how the timeless wisdom of iwígara can enhance your own kinship with the natural world.

-

“A beautifully illustrated and philosophically uplifting guide to indigenous North American plant use… this lovely compendium will strike a chord with many a nature-loving reader.” B>Publishers WeeklyThe Ecological Landscape Alliance “Each profile fittingly begins with the plant’s story. We learn who it is, where it came from, its botanical family, and perhaps a story of how it came to be. This poignant introduction mirrors the way many indigenous people worldwide introduce themselves.” —The American Herb Association Quarterly “What makes this volume different than other plant compendiums are the stories, memories, and histories woven throughout. It’s this cultural context and Salmón’s graceful attention to detail that makes it unique.” —Spirit Bound Press

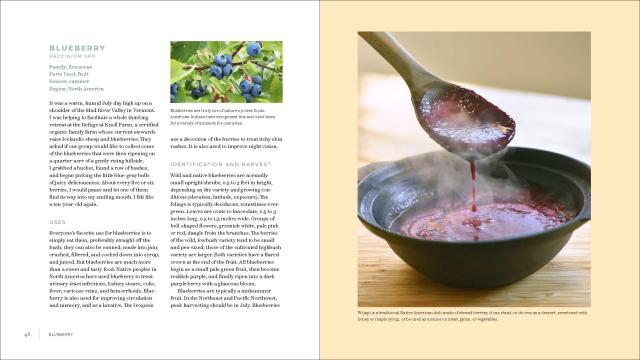

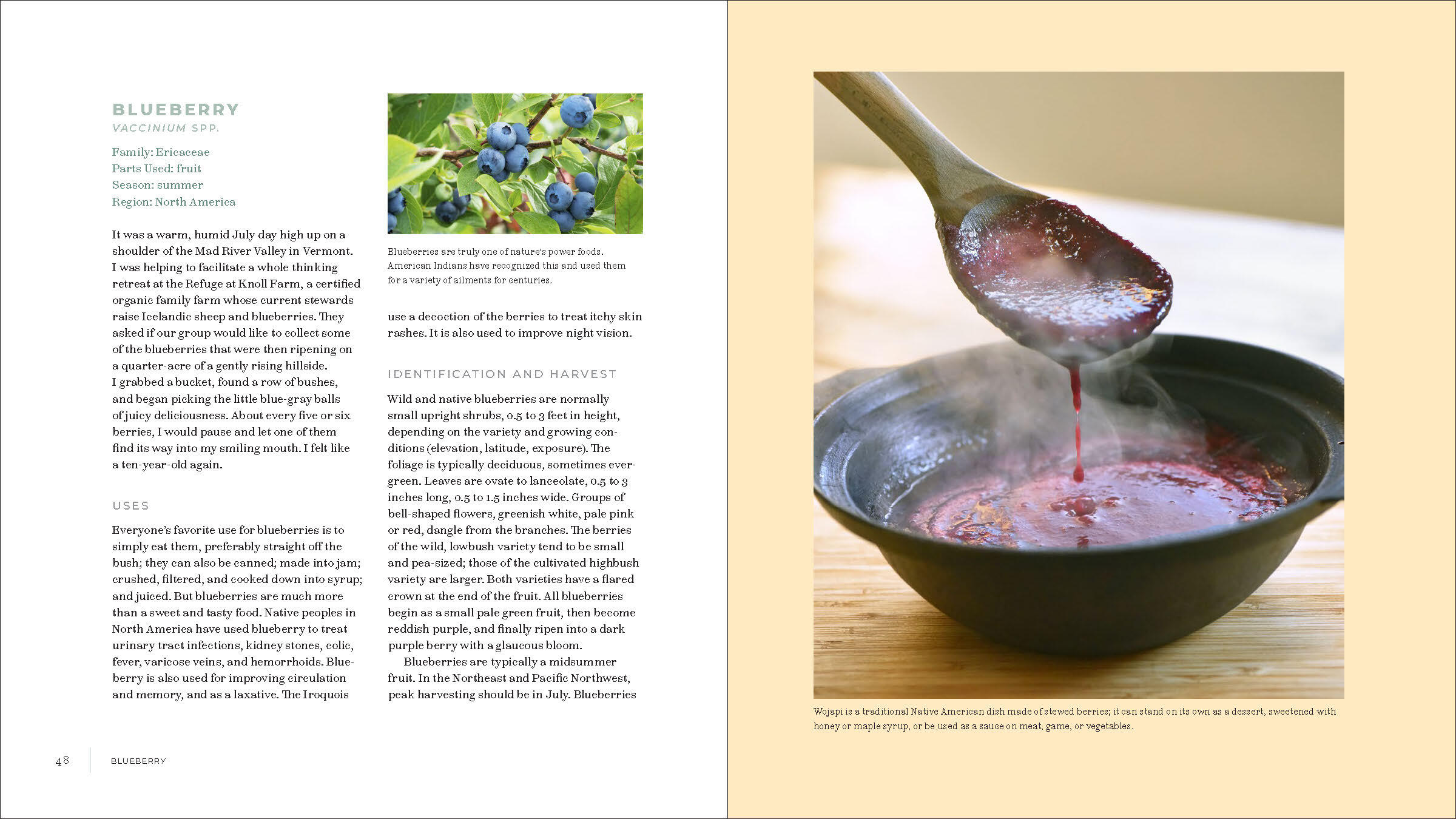

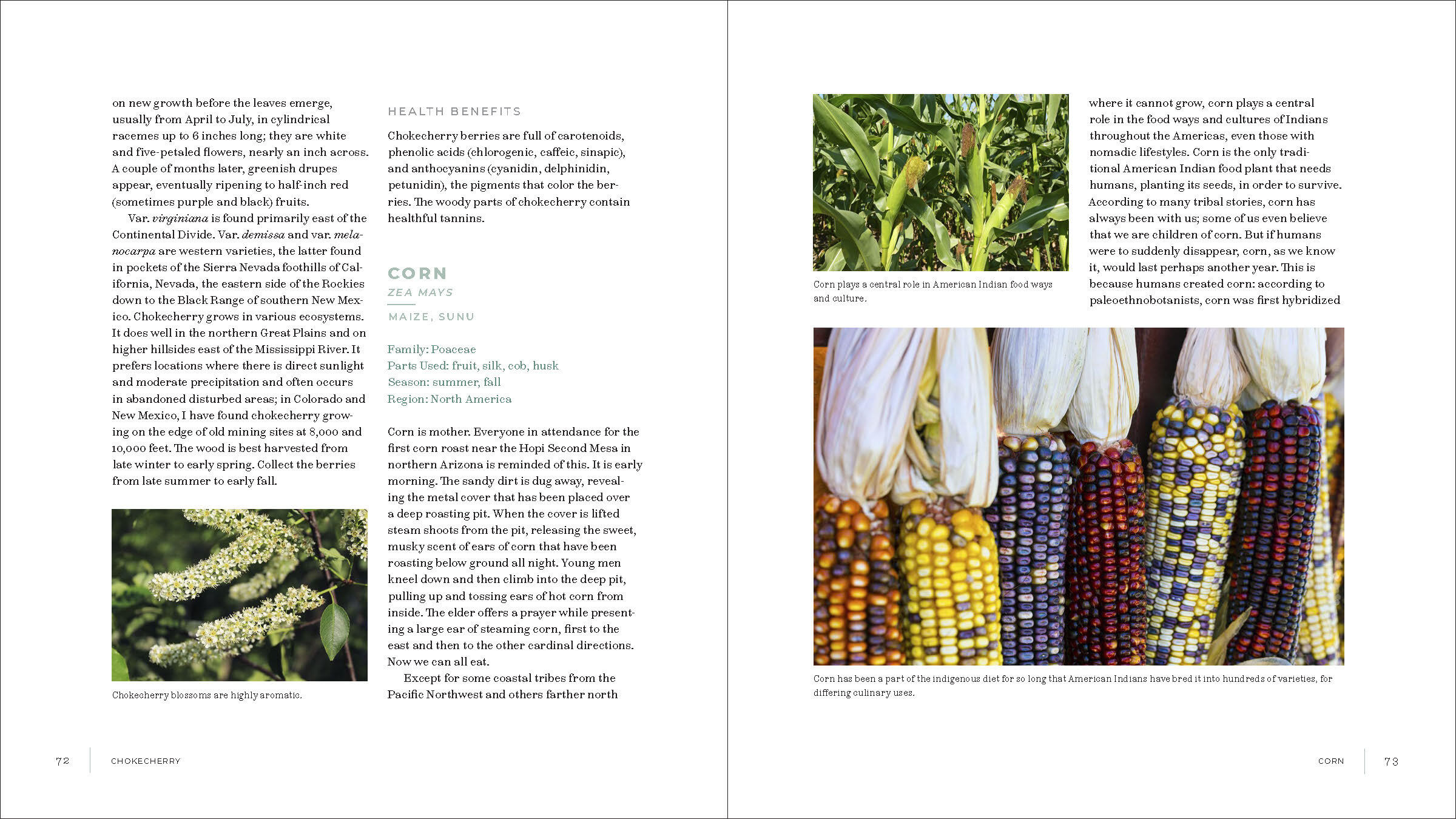

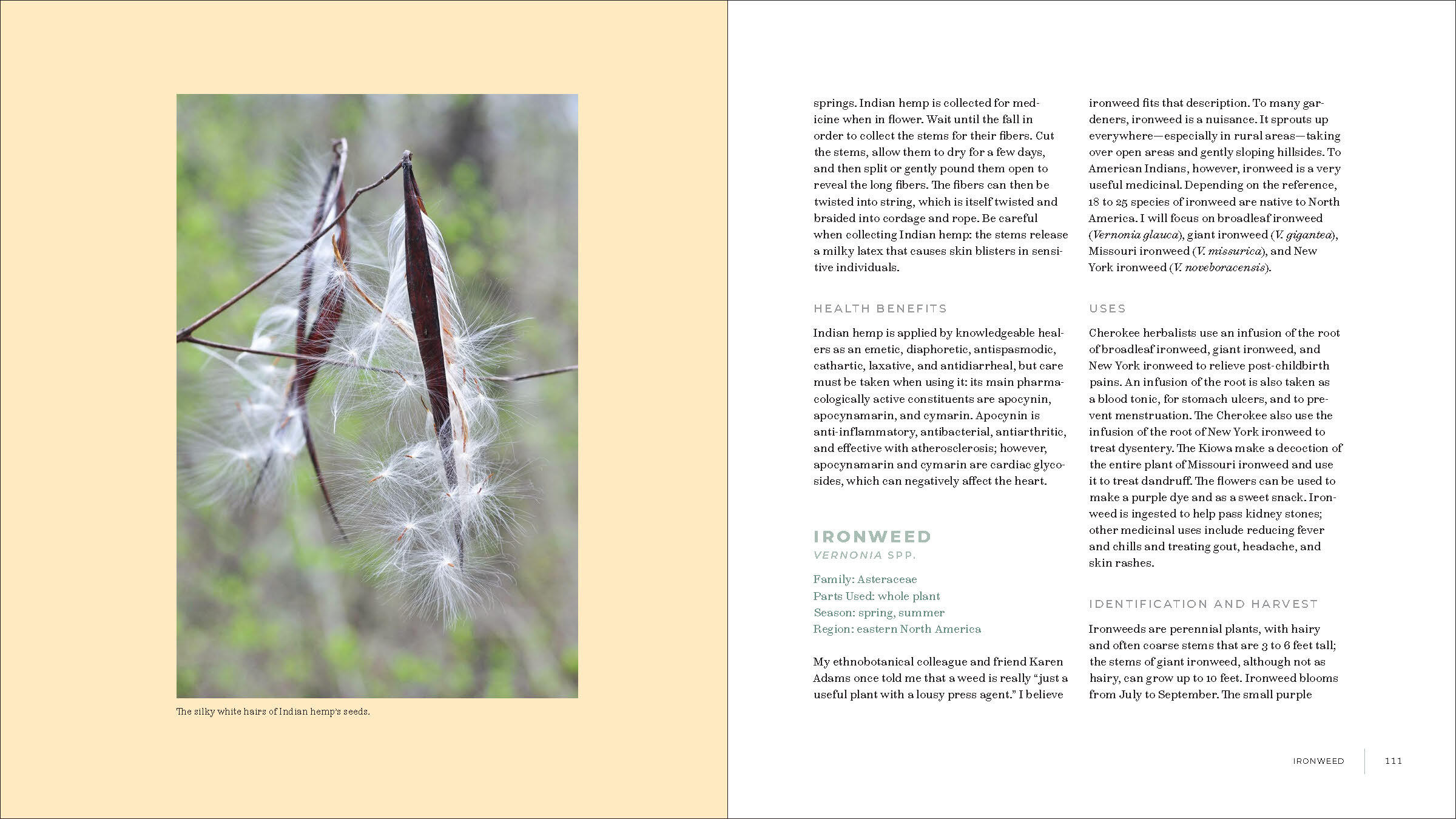

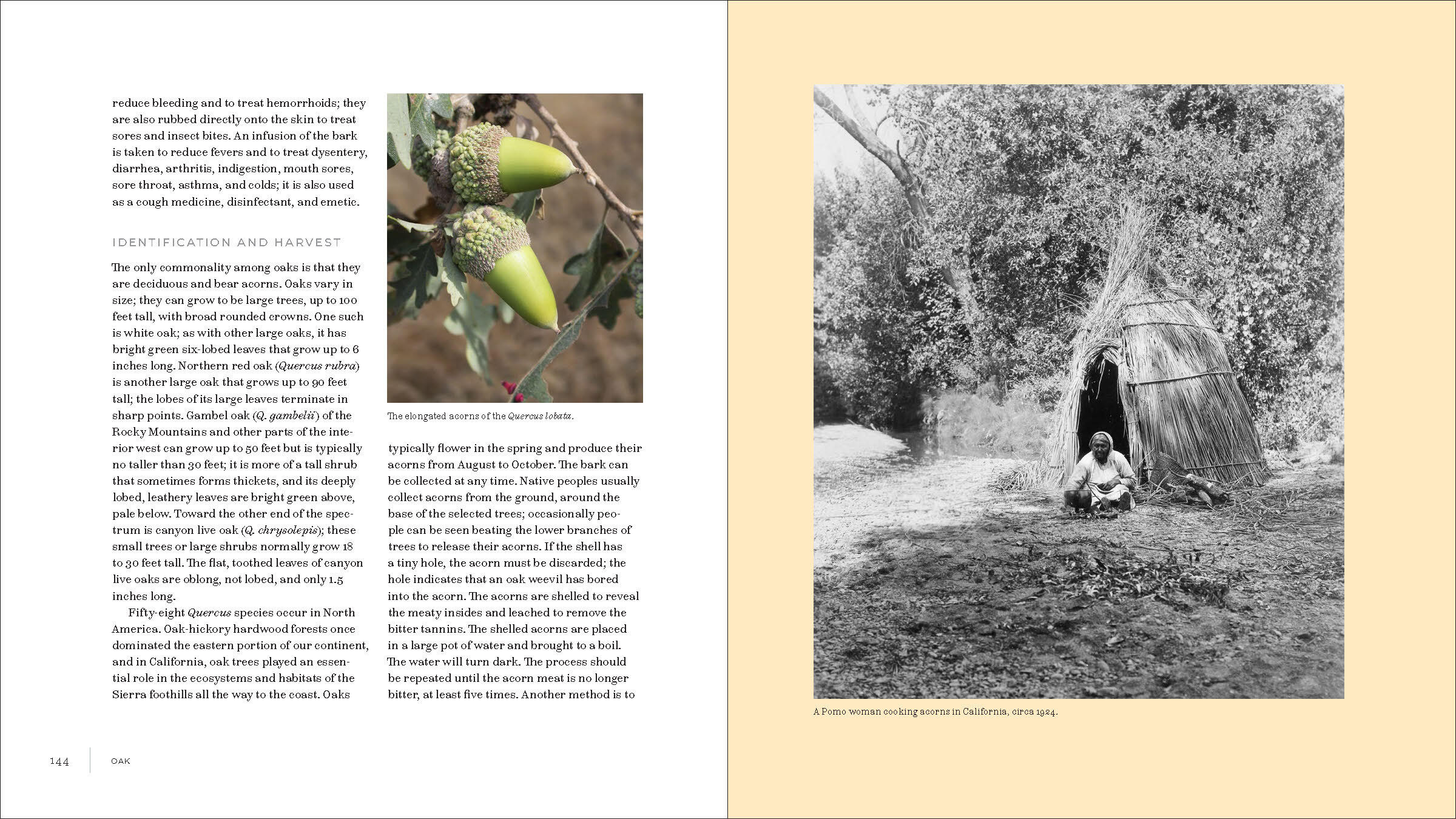

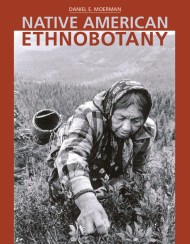

“Rich information about uses and traditional significance. Color photos of the plants and examples of the ways they are used bring the information to life.” —Booklist

“Iwígara is a rich compendium of 80 native North American plants that shines a light on their role in history, storytelling, food, and medicine.” —Martha Stewart Living

"A beautiful catalogue of 80 North American plants, revered by indigenous people for thousands of years for their nourishing, healing, and symbolic properties." —Gardens Illustrated

“I appreciate all of the practical information and lore contained in these descriptions, which will cause me to look at familiar plants such as the stinging nettle and the staghorn sumac in new ways.” —Hudson Valley 360

“Eighty humble plants and the wisdom of North American indigenous people add up to simple yet magnificent insights in Enrique Salmón's new book, Iwígara.” —East Bay Express

“Salmón explains the integral relationship between people and plants… He reveals the ways in which we are more tied to the natural world surrounding us than we may realize.” —Constant Wonder BYU Radio

“The Raramuri concept of iwígara, that all life is interconnected, shapes this accessible plant guide in which Native ethnobotanical scholar Salmon extends his advocacy for ethnobotanical justice and Indigenous rights.” —Booklist

“A wonderful resource.” -

“A beautifully illustrated and philosophically uplifting guide to indigenous North American plant use… this lovely compendium will strike a chord with many a nature-loving reader.” B>Publishers WeeklyThe Ecological Landscape Alliance

“Rich information about uses and traditional significance. Color photos of the plants and examples of the ways they are used bring the information to life.” —Booklist

“Iwígara is a rich compendium of 80 native North American plants that shines a light on their role in history, storytelling, food, and medicine.” —Martha Stewart Living

"A beautiful catalogue of 80 North American plants, revered by indigenous people for thousands of years for their nourishing, healing, and symbolic properties." —Gardens Illustrated

“I appreciate all of the practical information and lore contained in these descriptions, which will cause me to look at familiar plants such as the stinging nettle and the staghorn sumac in new ways.” —Hudson Valley 360

“Eighty humble plants and the wisdom of North American indigenous people add up to simple yet magnificent insights in Enrique Salmón's new book, Iwígara.” —East Bay Express

“Salmón explains the integral relationship between people and plants… He reveals the ways in which we are more tied to the natural world surrounding us than we may realize.” —Constant Wonder BYU Radio

“The Raramuri concept of iwígara, that all life is interconnected, shapes this accessible plant guide in which Native ethnobotanical scholar Salmon extends his advocacy for ethnobotanical justice and Indigenous rights.” —Booklist

“A wonderful resource.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use