Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

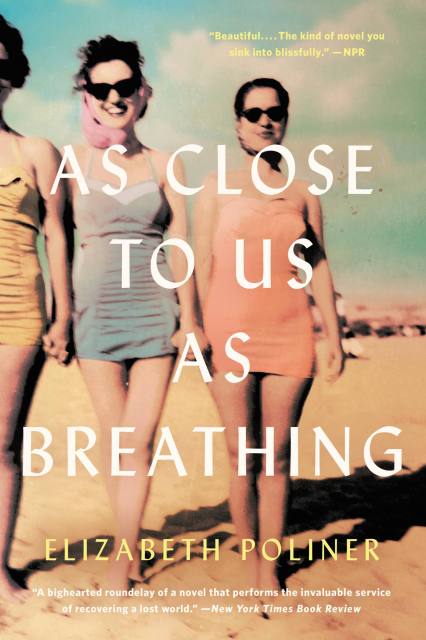

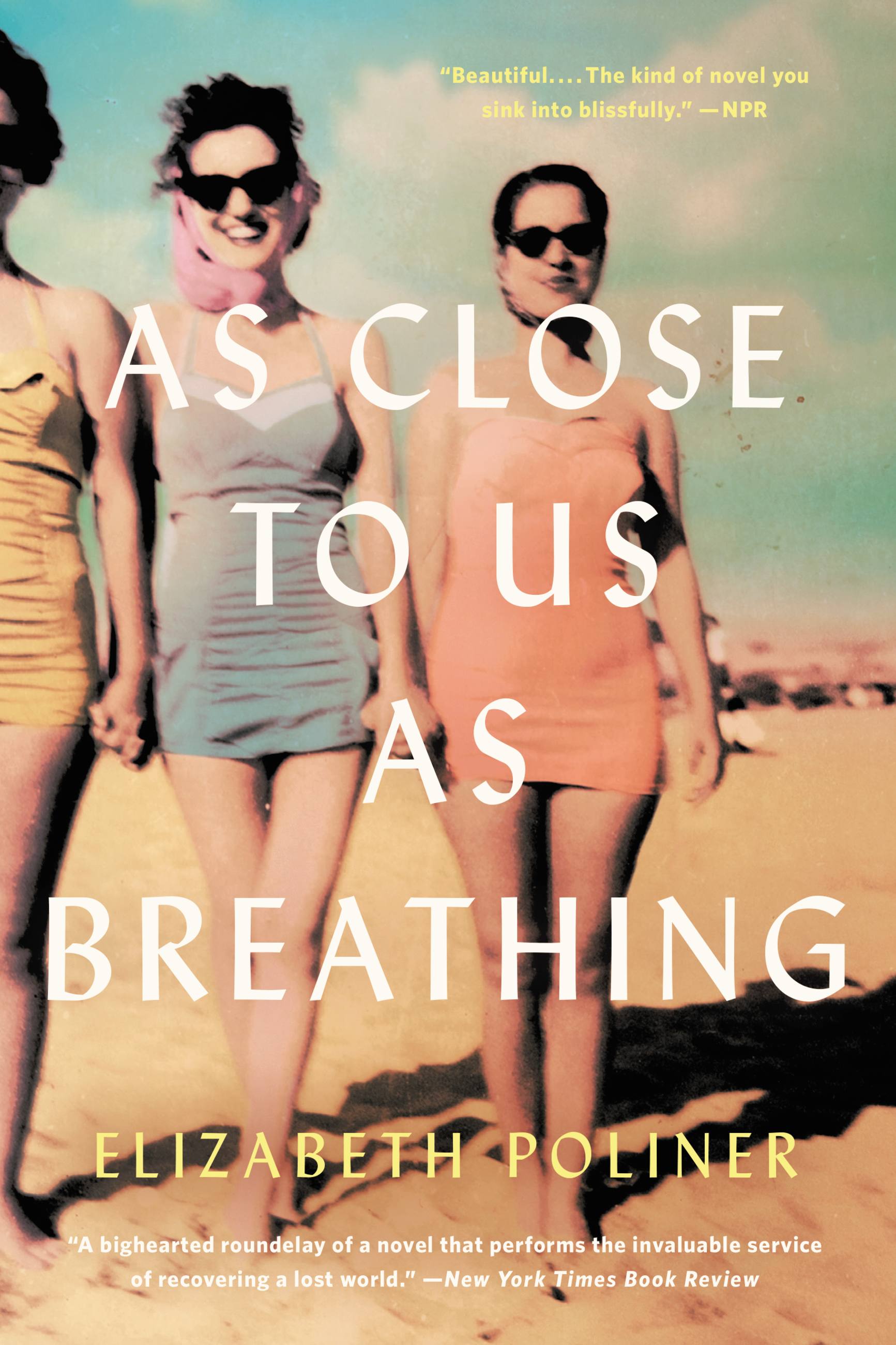

As Close to Us as Breathing

A Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 15, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A multigenerational family saga about the long-lasting reverberations of one tragic summer by “a wonderful talent [who] should be read widely” (Edward P. Jones).

In 1948, a small stretch of the Woodmont, Connecticut shoreline, affectionately named “Bagel Beach,” has long been a summer destination for Jewish families. Here sisters Ada, Vivie, and Bec assemble at their beloved family cottage, with children in tow and weekend-only husbands who arrive each Friday in time for the Sabbath meal.

During the weekdays, freedom reigns. Ada, the family beauty, relaxes and grows more playful, unimpeded by her rule-driven, religious husband. Vivie, once terribly wronged by her sister, is now the family diplomat and an increasingly inventive chef. Unmarried Bec finds herself forced to choose between the family-centric life she’s always known and a passion-filled life with the married man with whom she’s had a secret years-long affair.

But when a terrible accident occurs on the sisters’ watch, a summer of hope and self-discovery transforms into a lifetime of atonement and loss for members of this close-knit clan. Seen through the eyes of Molly, who was twelve years old when she witnessed the accident, this is the story of a tragedy and its aftermath, of expanding lives painfully collapsed. Can Molly, decades after the event, draw from her aunt Bec’s hard-won wisdom and free herself from the burden that destroyed so many others?

Elizabeth Poliner is a masterful storyteller, a brilliant observer of human nature, and in As Close to Us as Breathing she has created an unforgettable meditation on grief, guilt, and the boundaries of identity and love.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 15, 2016

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Lee Boudreaux Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316384117

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use