By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

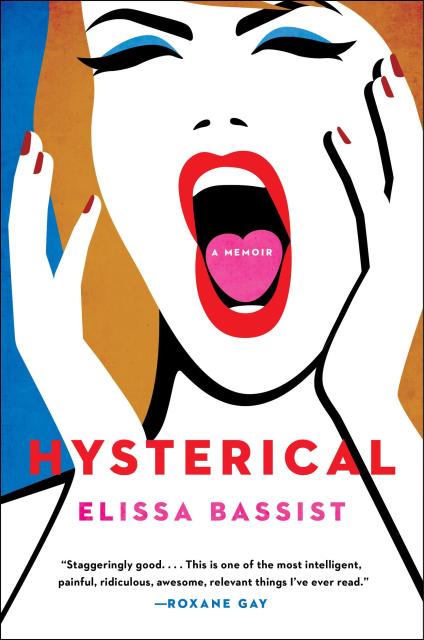

Hysterical

A Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 13, 2022

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306827396

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 13, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

SEMI-FINALIST FOR THE 2023 THURBER PRIZE FOR AMERICAN HUMOR • “A fiery cultural critique.” —Kirkus Reviews • “…a powerful, beautifully written, and utterly important book.”—New York Journal of Books

“Hysterical is staggeringly good. … This is one of the most intelligent, painful, ridiculous, awesome, relevant things I've ever read.” –Roxane Gay

“…an impressive debut. Elissa Bassist wrote it like a motherfucker."–Cheryl Strayed

Acclaimed humor writer Elissa Bassist shares her journey to reclaim her authentic voice in a culture that doesn't listen to women in this medical mystery, cultural criticism, and rallying cry.

Between 2016 and 2018, Elissa Bassist saw over twenty medical professionals for a variety of mysterious ailments. She had what millions of American women had: pain that didn’t make sense to doctors, a body that didn’t make sense to science, and a psyche that didn’t make sense to mankind. Then an acupuncturist suggested that some of her physical pain could be caged fury finding expression, and that treating her voice would treat the problem.

It did.

Growing up, Bassist's family, boyfriends, school, work, and television shows had the same expectation for a woman’s voice: less is more. She was called dramatic and insane for speaking her mind. She was accused of overreacting and playing victim for having unexplained physical pain. She was ignored or rebuked (like so many women throughout history) for using her voice “inappropriately” by expressing sadness or suffering or anger or joy. Because of this, she said “yes” when she meant “no”; she didn’t tweet #MeToo; and she never spoke without fear of being "too emotional." She felt rage, but like a good woman, she repressed it.

In her witty and incisive debut, Bassist explains how girls and women internalize and perpetuate directives about their voices, making it hard to “just speak up” and “burn down the patriarchy.” But then their silence hurts them more than anything they could ever say. Hysterical is a memoir of a voice lost and found, a primer on new ways to think about a woman’s voice—about where it’s being squashed and where it needs amplification—and a clarion call for readers to unmute their voice, listen to it above all others, and use it again without regret.

-

“Hysterical is staggeringly good. I am speechless, which as a reader, is a rare thing for me. I really just have a bunch of blubbering accolades to shower on Elissa. This is one of the most intelligent, painful, ridiculous, awesome, relevant things I've ever read. I am impressed.”Roxane Gay

-

"In her dazzling memoir, Elissa Bassist cuts right to the heart and delivers an intimate, unexpected, funny, and original yet universal story about voice and silence and illness. Hysterical is an impressive debut. Elissa Bassist wrote it like a motherfucker."Cheryl Strayed

-

“Funny and furious and sharp and bursting with everything we’re urged to hold inside, Elissa Bassist’s Hysterical is a god damn delight.”Rebecca Traister

-

“I LOVE LOVE LOVE LOVE LOVE Elissa's writing. That was five loves....Quite a special, strong, funny voice."Joey Soloway, creator/writer/director/Emmy-award winner of Transparent

-

"One of the qualities I appreciated most about Hysterical is the way the author subtly and gracefully links her deeply personal life story to compelling questions about women’s sexuality, literature, history. We never notice her doing the connecting; the larger themes and analysis are seamlessly woven into the intimate story. She makes us think and care about not simply what happened to her, but about women’s bodies, our continued detachment from our own desire, our own complicity in the culture of sexual violence…This artful, moving work of creative nonfiction transcends the self, while keeping us rooted in the most intimate of stories.”Danzy Senna, bestselling author of Caucasia and judge of the New School Chapbook Competition

-

"Before reading [Hysterical], I hadn’t found much literature (especially witty literature) on how misogyny shows up in the body. What a relief to find a book that articulates so many frustrating and familiar experiences; I couldn’t put my highlighter down.... Hysterical examines who gets to speak and why, society’s fascination with dead girls, the “rape-culture iceberg,” and how to reclaim your voice."The Cut

-

"Bassist’s memoir is both a detailed diagnostic and a measured prescription for women, specifically American women and all those who have the capacity for pregnancy, at this particularly patriarchal juncture in a post-Roe time. At once self-examining and dismantling, Bassist’s unflinching wit and dry humor deliver a hybrid, almost mosaic, memoir that weaves personal essay, feminist criticism, research, and social commentary."Chicago Review of Books

-

"Part memoir, part cultural critique, part manifesto, Hysterical is a tour de force, a powerful response and critique of the subjugation of girls and women across all aspects of our culture—healthcare, workplaces, dating and sex (heterosexual, that is), pop culture (publishing, television, film), and of language itself. 'Patriarchy,' she writes, 'is our mother tongue and preexisting condition.' "New York Journal of Books

-

"Disruptive, tender, and beautiful, this book is a reversal of women’s apologies and a demand for more."Library Journal Starred Review

-

"A sharp examination of life in “a culture where men speak and women shut up"... [Bassist's] memoir stands as proof of an arduous process of healing. A fiery cultural critique."Kirkus Review

-

"Bassist's resounding voice will echo in readers' heads long after they have finished the book. This book a reckoning with an unjust power system that hurts everyone."Booklist

-

"To be a woman is to relate to Elissa Bassist’s fierce and funny new memoir, Hysterical, a searing indictment of the patriarchal and misogynistic medical system that so often belittles, ignores, and seeks to silence women’s voices. ... Thus, this impassioned memoir, which critiques “a culture where men speak and women shut up,” was born, and Bassist became definitively uncaged. Hysterical is for the women who are tired of being ignored, shamed, overmedicated, and misunderstood."Shondaland

-

"Part-memoir, part-manifesto, Hysterical asks women to tap into their anger, sadness, and joy— and to no longer silence themselves in the face of misogyny and the patriarchy."The Millions - Most Anticipated

-

"Hysterical felt like a kind of a breakthrough, a celebratory whoop and a call to action all in one, even for someone who has identified as a feminist for decades. As I finished it, I found myself wanting to press it into the hands of everyone I know because whether it is a revelation or a reminder, Hysterical is part of the essential story of being female today."Datebook, San Francisco Chronicle

-

"Bassist’s command of prose is as honed as the muscles of an Olympic gymnast. Her intelligence shines; her wit is so dry it is parched. A humorist by trade, she earned her battle scars in comedy, a field which has made some strides towards inclusion but where the majority view still seems to be that the best way to be a funny woman is to be funny, or a woman, but not both at once."Hippocampus Magazine

-

"Bassist manages to be funny, precise, and intimate while dissecting the mess of modern feminism—wow, women can have it all!"Electric Lit

-

"[Hysterical] touches on so many things that ... women deal with in the world. It weaves the science in — in a great way where you're both reading about what this woman has gone through, but you're learning something at the same time."Daisy Rosario, NPR

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use