Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

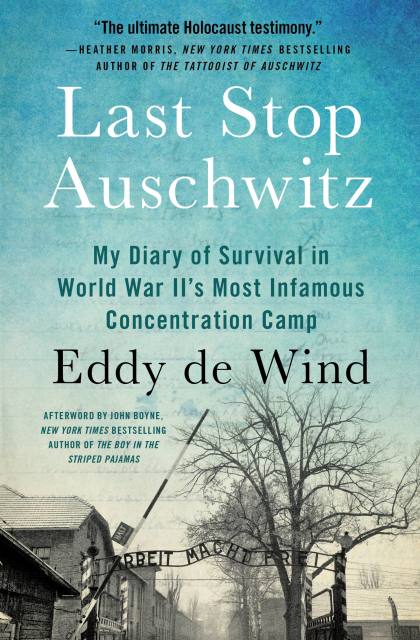

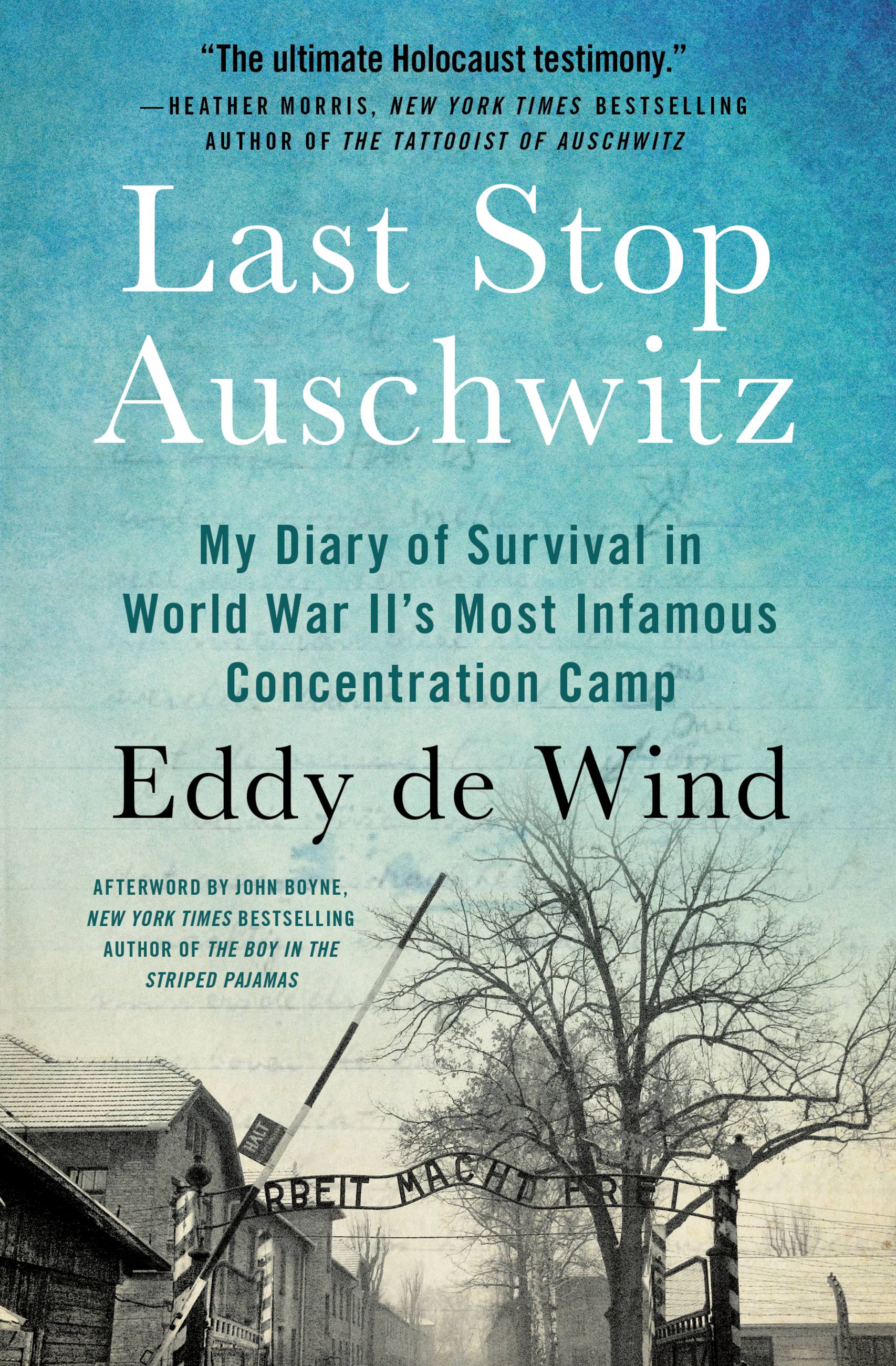

Last Stop Auschwitz

My Story of Survival from within the Camp

Contributors

By Eddy de Wind

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 21, 2020

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538701416

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Digital download $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 21, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“We know that there is only one ending to this, only one liberation from this barbed wire hell: death.” — Eddy de Wind

Written in the camp itself in the weeks following the Red Army’s liberation of the camp, Last Stop Auschwitz is the raw, true account of Eddy’s experiences at Auschwitz. In stunningly poetic prose, he provides unparalleled access to the horrors he faced in the concentration camp. Including photos from Eddy’s life before, during, and after the Holocaust, this poignant memoir is at once a moving love story, a detailed portrayal of the atrocities of Auschwitz, and an intelligent consideration of the kind of behavior — both good and evil — people are capable of. Never before published in English, this book is a vital and enduring document: a testament to the strength of the human spirit, and a warning against the depths we can sink to when prejudice is given power.

In 1943, amidst the start of German occupation, Eddy de Wind worked as a doctor at Westerbork, a Dutch transit camp. His mother had been taken to this camp by Nazis but Eddy was assured by the Jewish Council she would be freed in exchange for his labor. He later found out she’d already been transferred to Auschwitz.

While at Westerbork, he fell in love with a woman named Friedel and they married. One year later, they were transported to Auschwitz. Upon arrival, Friedel and Eddy were separated — Eddy forced to work as a medical assistant in one barrack, Friedel at the mercy of Nazi experimentation in a nearby block. Sneaking moments with his beloved and communicating whenever they could, Eddy longed for the day he could be free with Friedel . . .