Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

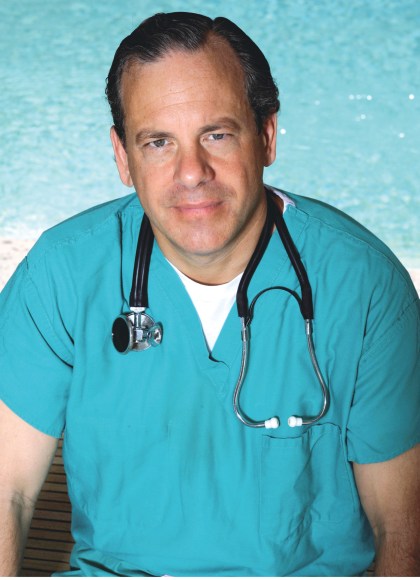

Touching Heaven

A Cardiologist's Encounters with Death and Living Proof of an Afterlife

Contributors

With Kris Bearss

Read by Dr. Chauncey Crandall

Formats and Prices

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $34.00 $44.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 15, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

How a doctor’s glimpses of eternity confirmed everything he believed about God, suffering, life on earth, and what happens after death.

Dr. Chauncey Crandall knows his patients well. When they are dying, he sits at the bedside with them and holds their hands. He prays with them. Sometimes he can feel what they feel and see what they see. At other times his patients have near-death experiences and “come back” with astonishing descriptions of the afterlife. In TOUCHING HEAVEN, Dr. Crandall reveals how what he has seen and heard has convinced him that God is real, that we are created for a divine purpose, that death is not the end, that we will see our departed loved ones again, and that we are closer to the next world than we think.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 15, 2015

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478959595

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use