Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

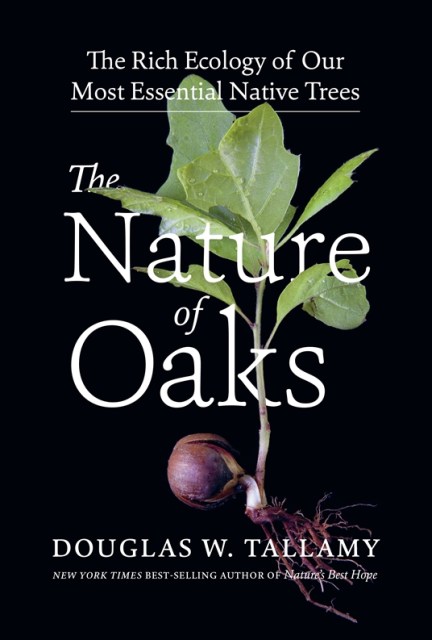

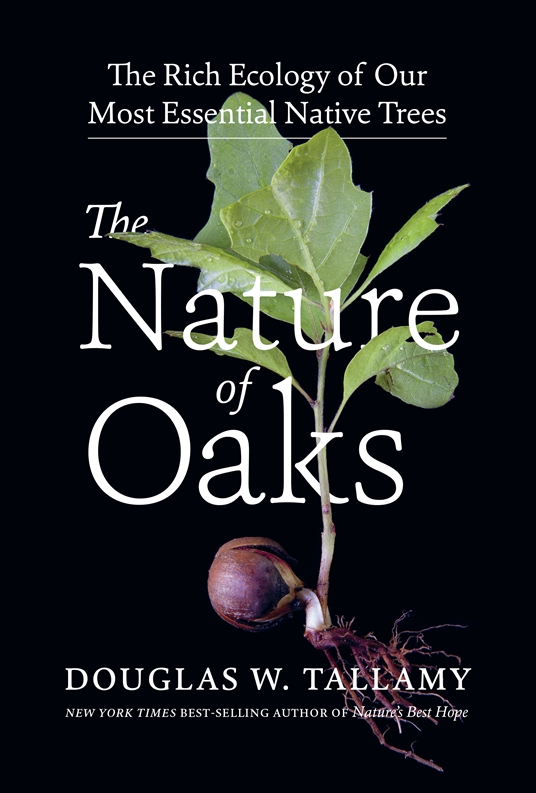

The Nature of Oaks

The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$36.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 30, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“With our hearts and minds focused on the stewardship of the only planet we have, the best way to engage in a hopeful future is to plant oaks! Let this book be your inspiration and guide.” —The American Gardener

With Bringing Nature Home, Doug Tallamy changed the conversation about gardening in America. His second book, the New York Times bestseller Nature’s Best Hope, urged homeowners to take conservation into their own hands. Now, he turns his advocacy to one of the most important species of the plant kingdom—the mighty oak tree.

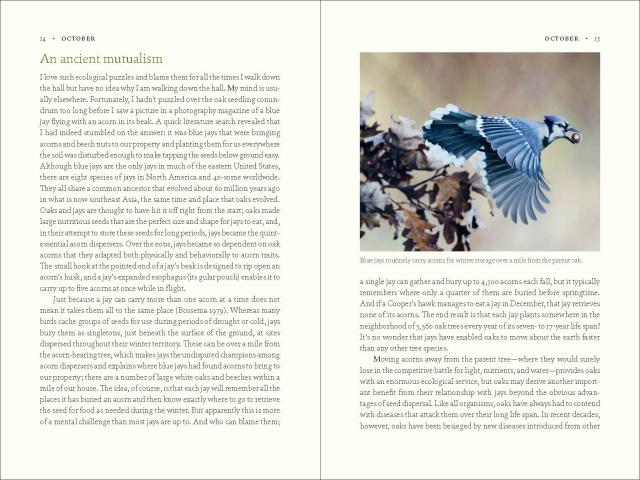

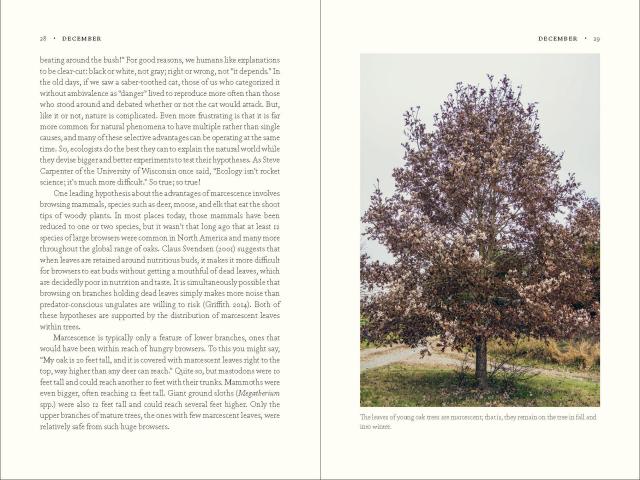

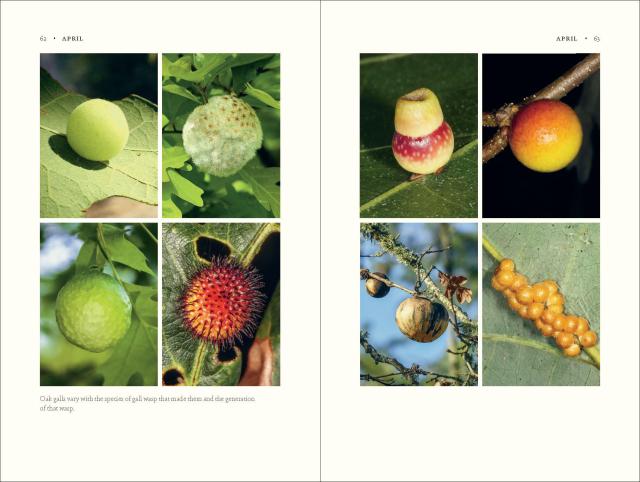

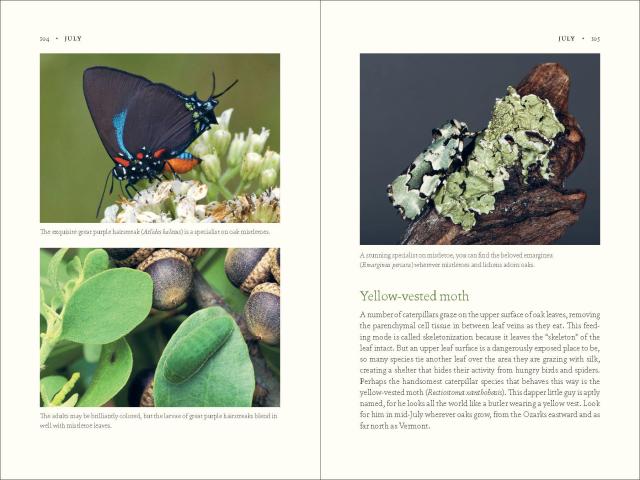

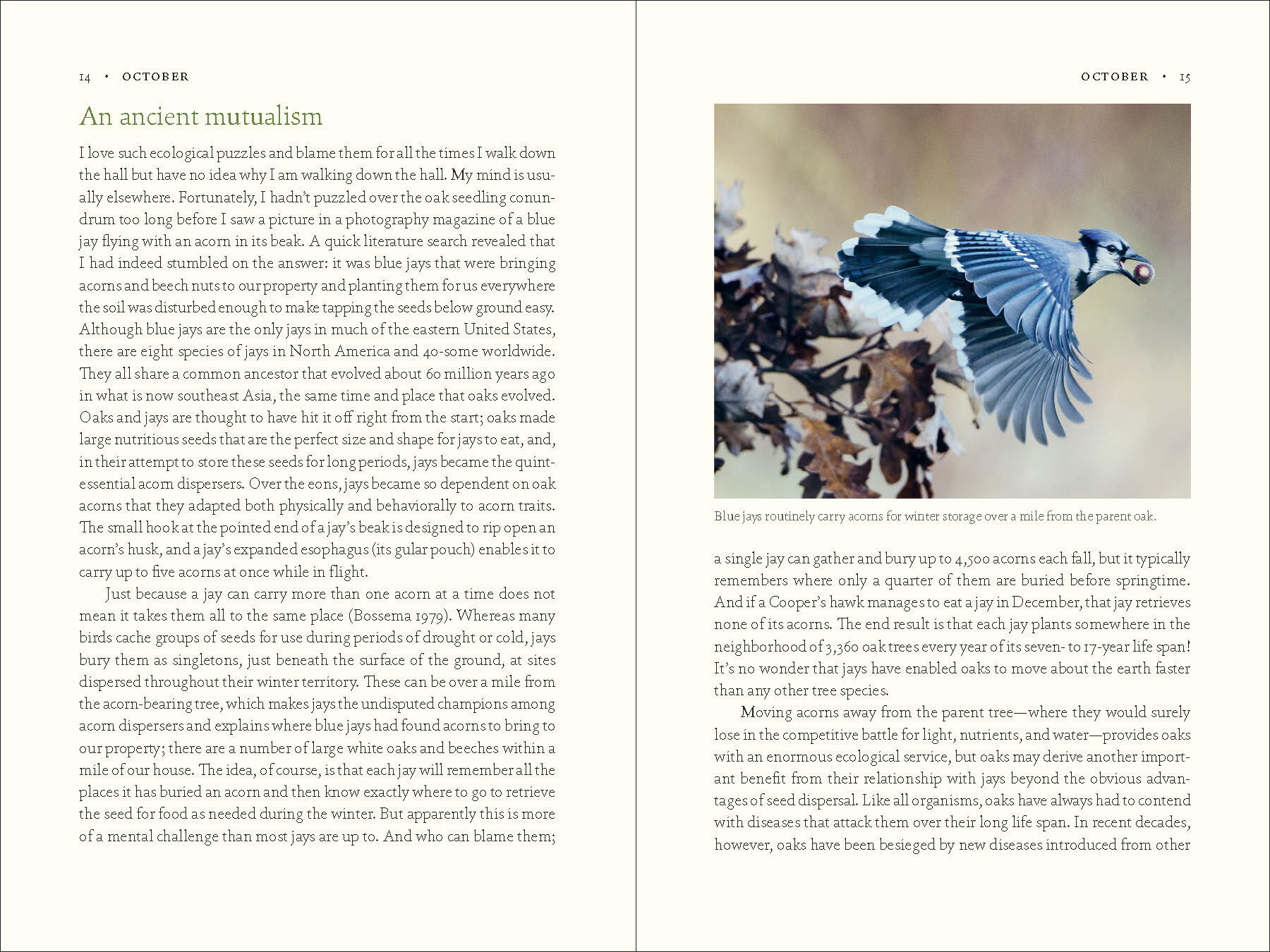

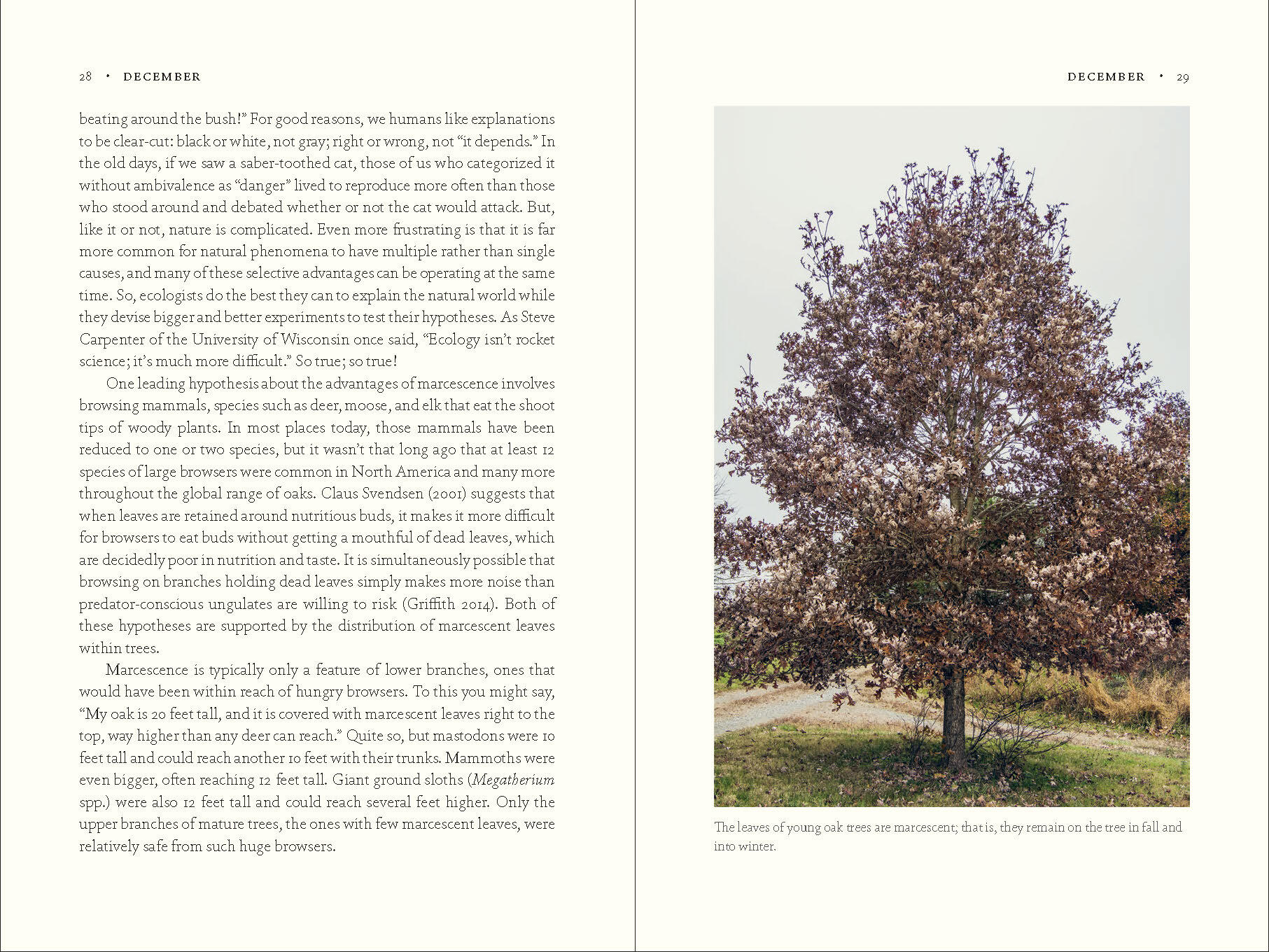

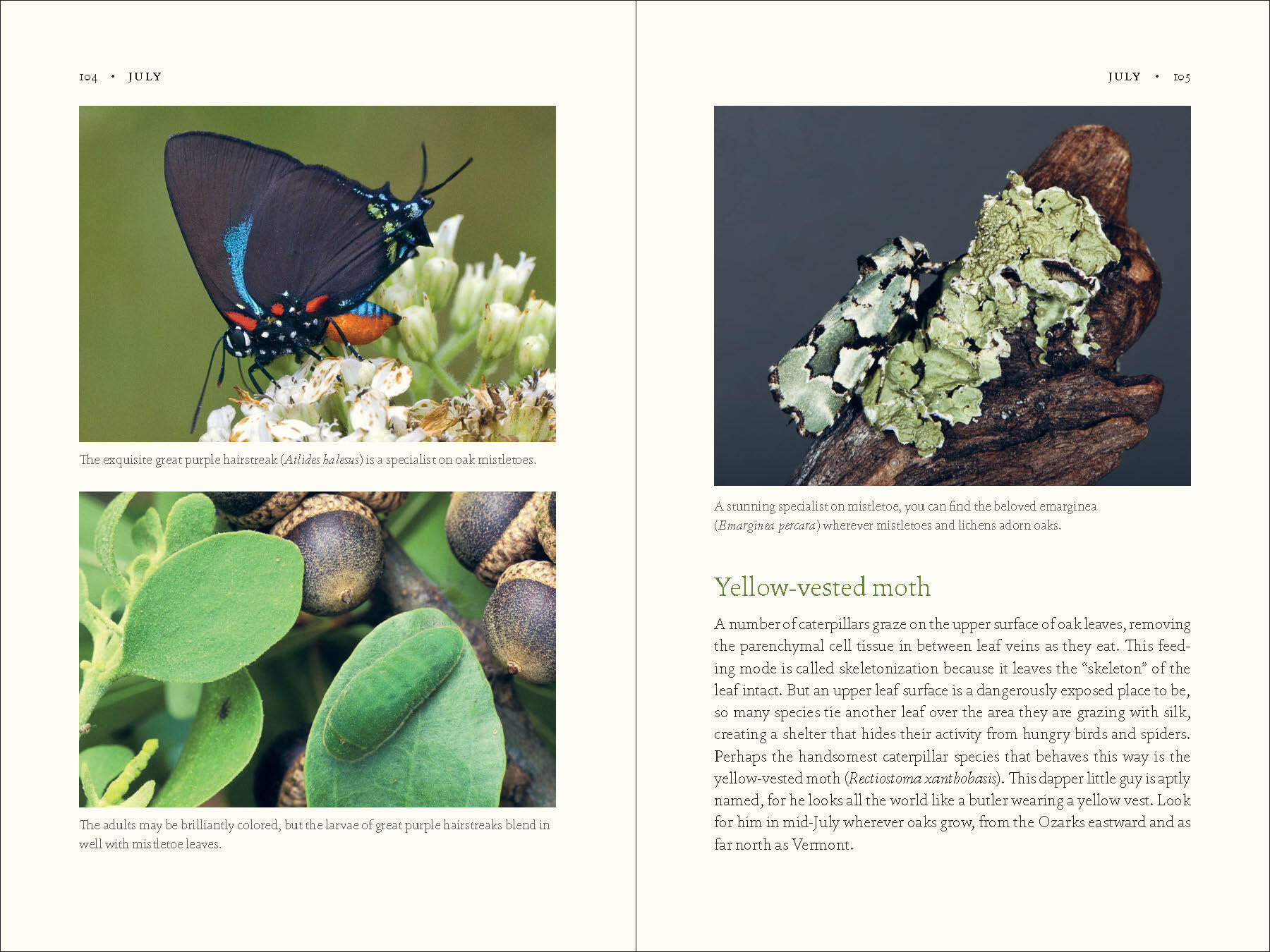

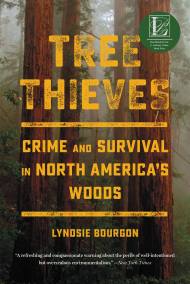

Oaks sustain a complex and fascinating web of wildlife. The Nature of Oaks reveals what is going on in oak trees month by month, highlighting the seasonal cycles of life, death, and renewal. From woodpeckers who collect and store hundreds of acorns for sustenance to the beauty of jewel caterpillars, Tallamy illuminates and celebrates the wonders that occur right in our own backyards. He also shares practical advice about how to plant and care for an oak, along with information about the best oak species for your area. The Nature of Oaks will inspire you to treasure these trees and to act to nurture and protect them.

Genre:

-

“There’s a payoff for the environment, yes, but also for each of us, in the bonds of personal connection. Tallamy feels it, down to the last acorn.” —The New York Times

“The sturdy, steadfast oak is the perfect tree for troubled times.” —Washington Post

“An affectionate yet scientifically rich look at an essential ingredient of the environment… A welcome addition to any tree hugger’s library.” —Kirkus

“An excellent companion to Nature’s Best Hope” —Booklist

“Douglas W. Tallamy has spread a message of people-powered biodiversity, to say that if humans have crowded out nature across the world, they can also invite it back in at close range.” —Landscape Architecture Magazine

“The Nature of Oaks reads like a biography, chronicling the life of these symbols of strength and their relationships over the seasons with numerous characters of nature… It’s also practical, offering advice on selecting the best oak species for your area, and planting and caring for America’s National Tree.” —The Oregonian

“Doug Tallamy’s personal detail and his conversational writing style keep the book relatable and readable while it delves into scientific matters.” —Horticulture

“Packed with fascinating stories of ecological connections and wonders, this beautiful book is a hymn to the keystones of the forest, the oaks. A timely and much needed call to plant, protect, and delight in these diverse, life-giving giants.” —David George Haskell, author of Pulitzer finalist, The Forest Unseen, and Burroughs Medalist, The Songs of Trees; Professor, University of the South

"Powerfully engaging from start to finish, The Nature of Oaks is joyful, scientific storytelling at its best." —Rick Darke, landscape designer, lecturer, photographer, and coauthor of Gardens of the High Line

“A fascinating and compelling book devoted to native oaks… With our hearts and minds focused on the stewardship of the only planet we have, the best way to engage in a hopeful future is to plant oaks, lots of them! Let this book be your inspiration and guide.” —The American Gardener

“In this new and enlightening book, New York Times bestselling author Douglas W. Tallamy focuses his attention on the great monolith of the arboreal world: the mighty oak! It’s a rich explanation of exactly what oaks are and how they thrive, plus it’s got a bunch of tips for how you can maintain your own oaks!” —LitHub

“You will not finish the book without realizing how important oak trees are to our ecosystem and the hundreds of animals that rely on them.” —The Scholar“An essential resource on protecting and preserving the most important tree.” —The Advocate

"The Nature of Oaks expounds on the importance of incorporating oak trees into our gardens, highlighting how oaks are integrally intwined in all cogs of nature.” —Winston-Salem Journal

“This book is an essential read for anyone interested in the natural world, engagingly written and dense with insights and fascinating facts.” —The Los Altos Town Crier

“The Nature of Oaks describes the rich web of life around one of our most loved trees and tells how people can bring this into their own yards and communities.” —Yahoo!News

“Tallamy has long been advocating for homeowners to take conservation into their own hands. With this latest publication, he provides a guide to the mighty oak: from their place in the ecosystem to how to care for those in your own backyard.” —The Wolf River Conservancy

- On Sale

- Mar 30, 2021

- Page Count

- 200 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643260440

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use