Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

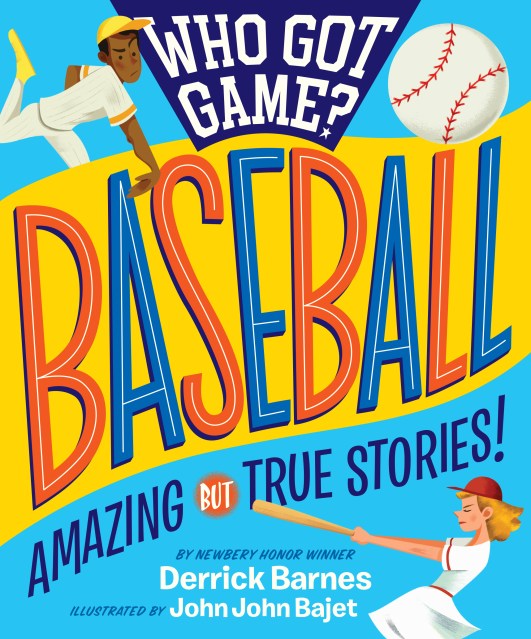

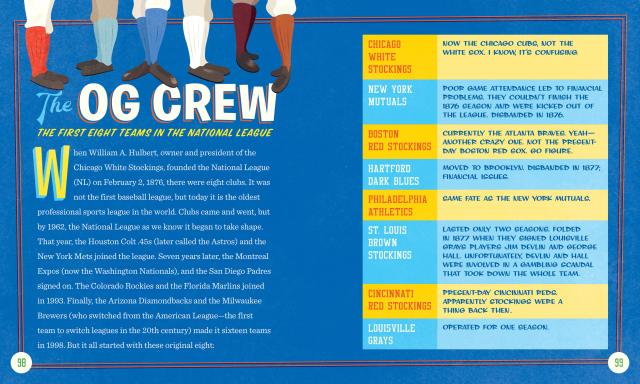

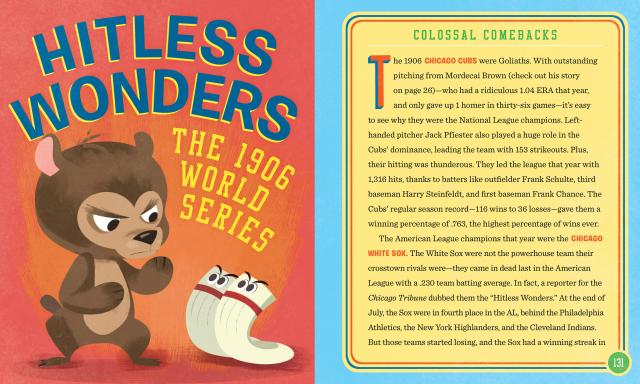

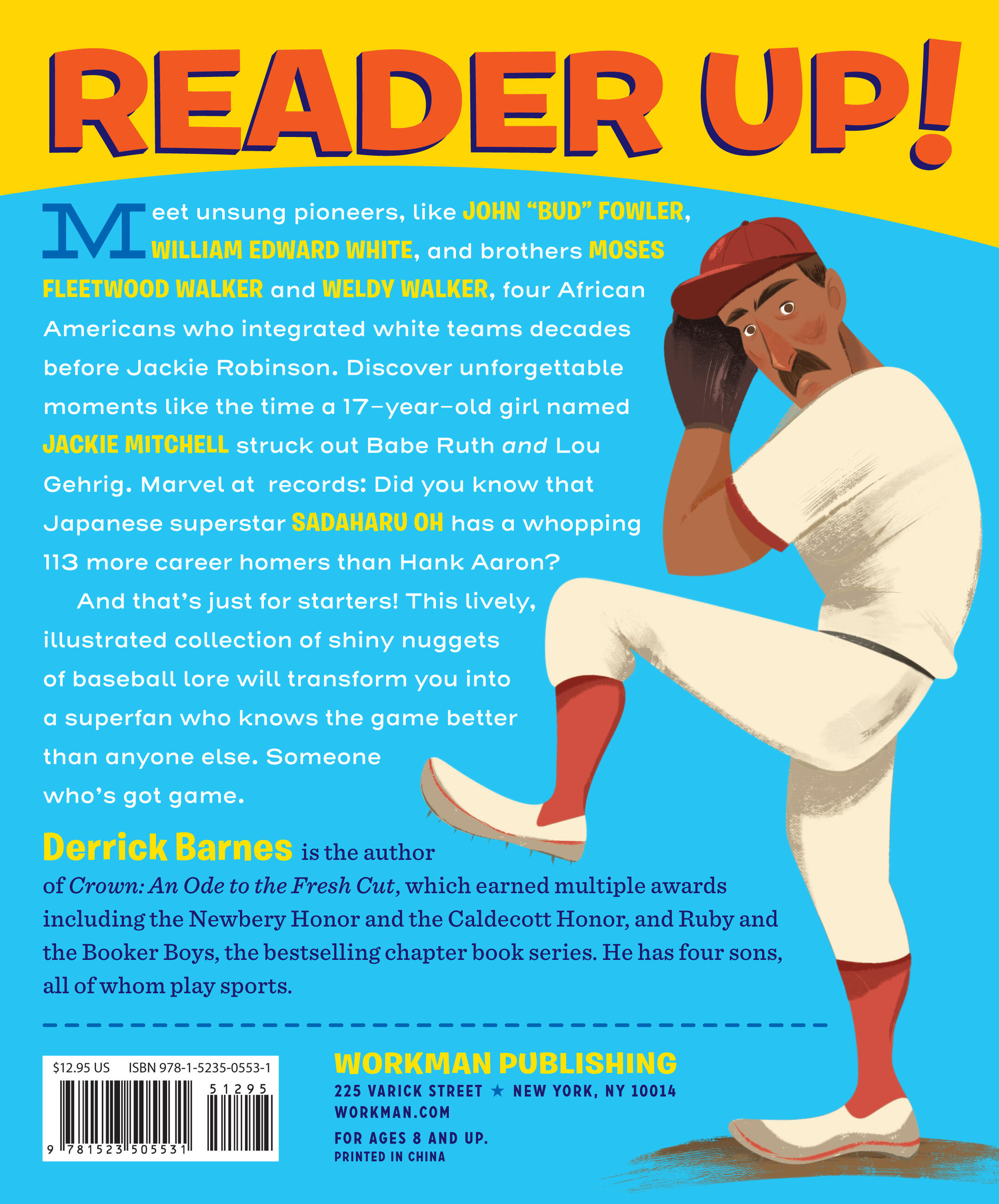

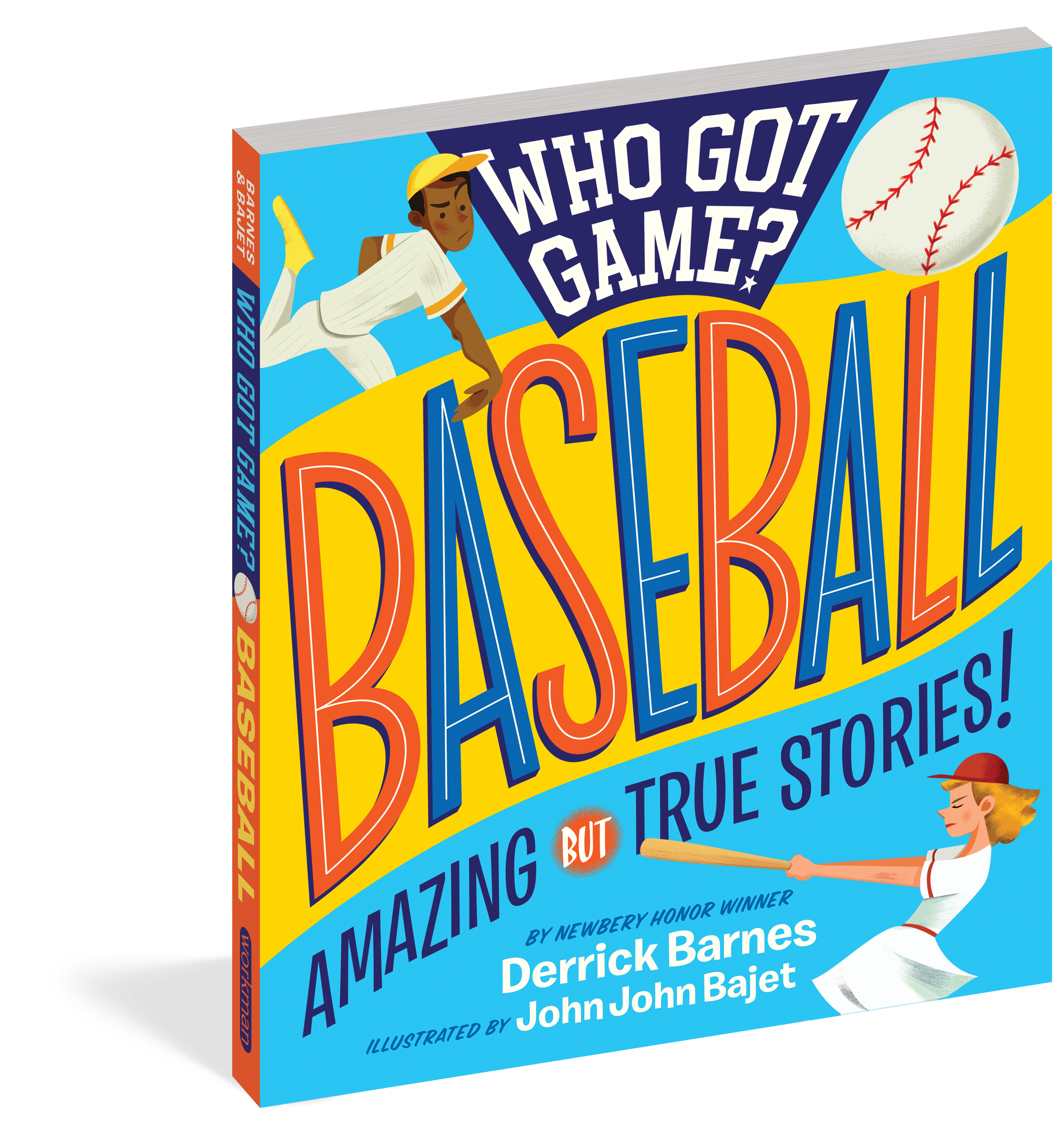

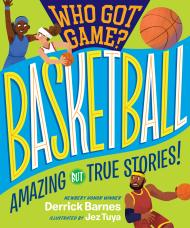

Who Got Game?: Baseball

Amazing but True Stories!

Contributors

Illustrated by John John Bajet

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 17, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

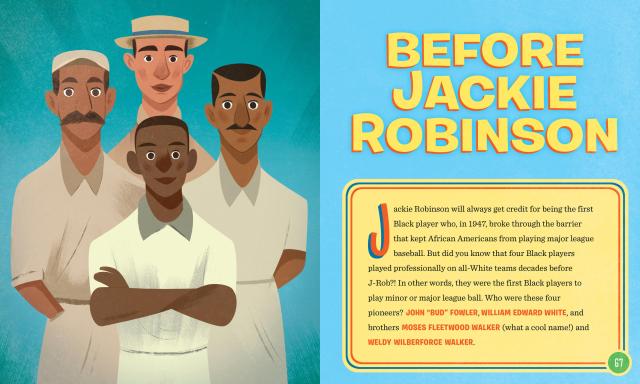

Meet unsung pioneers, like John “Bud” Fowler, William Edward White, and brothers Moses Fleetwood Walker and Weld Walker, four African Americans who integrated white teams decades before Jackie Robinson.

Discover unforgettable moments, like the time a 17-year old girl named Jackie Mitchell struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

Marvel at records. Did you know that Japanese superstar Sadaharu Oh has a whopping 113 more career homers than Hank Aaron?

And that’s just for starters! This lively illustrated collection of shiny nuggets of baseball lore will transform you into a superfan who knows the game better than anyone else. Someone who’s got game.

Series:

-

“A highly recommended first purchase. Readers will be sucked into this unique collection of ‘amazing but true stories’.” — School Library Journal, STARRED

"Inviting for newcomers and eye-opening for longtime fans, this one will have wide appeal in its exploration of the shortcomings and the beauty of America’s favorite pastime.” — Booklist, STARRED

“An ebullient collection of stunning comebacks, awesome athletes, and achievements both grand and dubious.” — Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- Mar 17, 2020

- Page Count

- 176 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523505531

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use