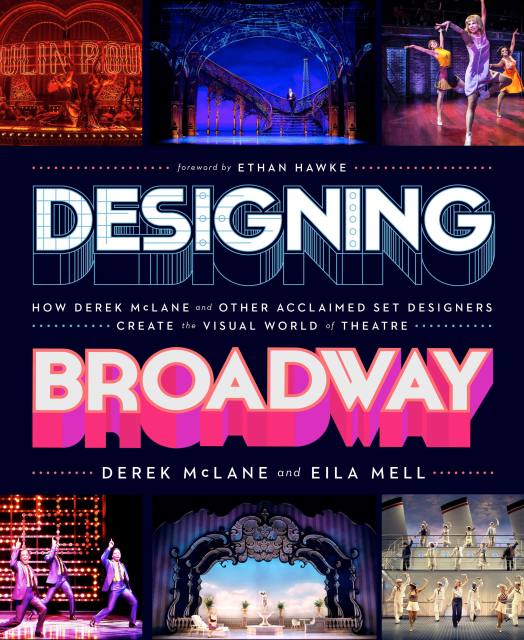

Designing Broadway

How Derek McLane and Other Acclaimed Set Designers Create the Visual World of Theatre

Contributors

By Derek McLane

By Eila Mell

Foreword by Ethan Hawke

Formats and Prices

Price

$45.00Price

$57.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $45.00 $57.00 CAD

- ebook $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 22, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Together with other leading set design and theatre talents, McLane invites us into the immersive and exhilarating experience of building the striking visual worlds that have brought so many of our favorite stories to life. Discover how designers generate innovative ideas, research period and place, solve staging challenges, and collaborate with directors, projectionists, costume designers, and other artists to capture the essence of a show in powerful scenic design.

With co-writer Eila Mell, McLane and contributors discuss Moulin Rouge!, Hamilton, Hadestown, Beautiful, and many more of the most iconic productions of our generation. Among the Broadway luminaries who contribute are John Lee Beatty, Danny Burstein, Cameron Crowe, Ethan Hawke, Moisés Kaufman, Carole King, Kenny Leon, Santo Loquasto, Kathleen Marshall, Lynn Nottage, David Rabe, Ruben Santiago-Hudson, Wallace Shawn, John Leguizamo, and Robin Wagner.

Filled with personal sketches and photographs fromthe artists’ archives, this stunningly designed book is truly a behind-the-scenes journey that theatre fans will love.

- On Sale

- Nov 22, 2022

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762480364

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use