Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

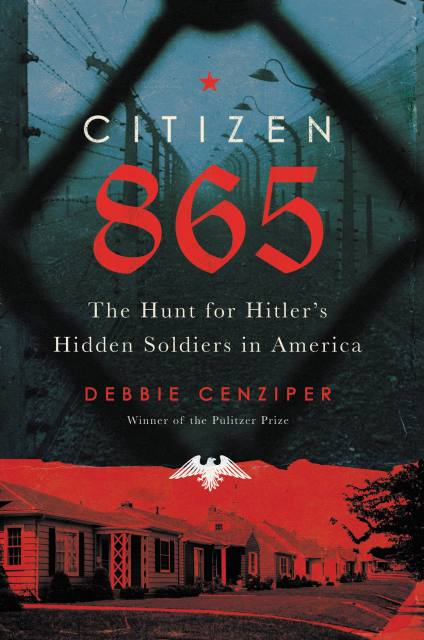

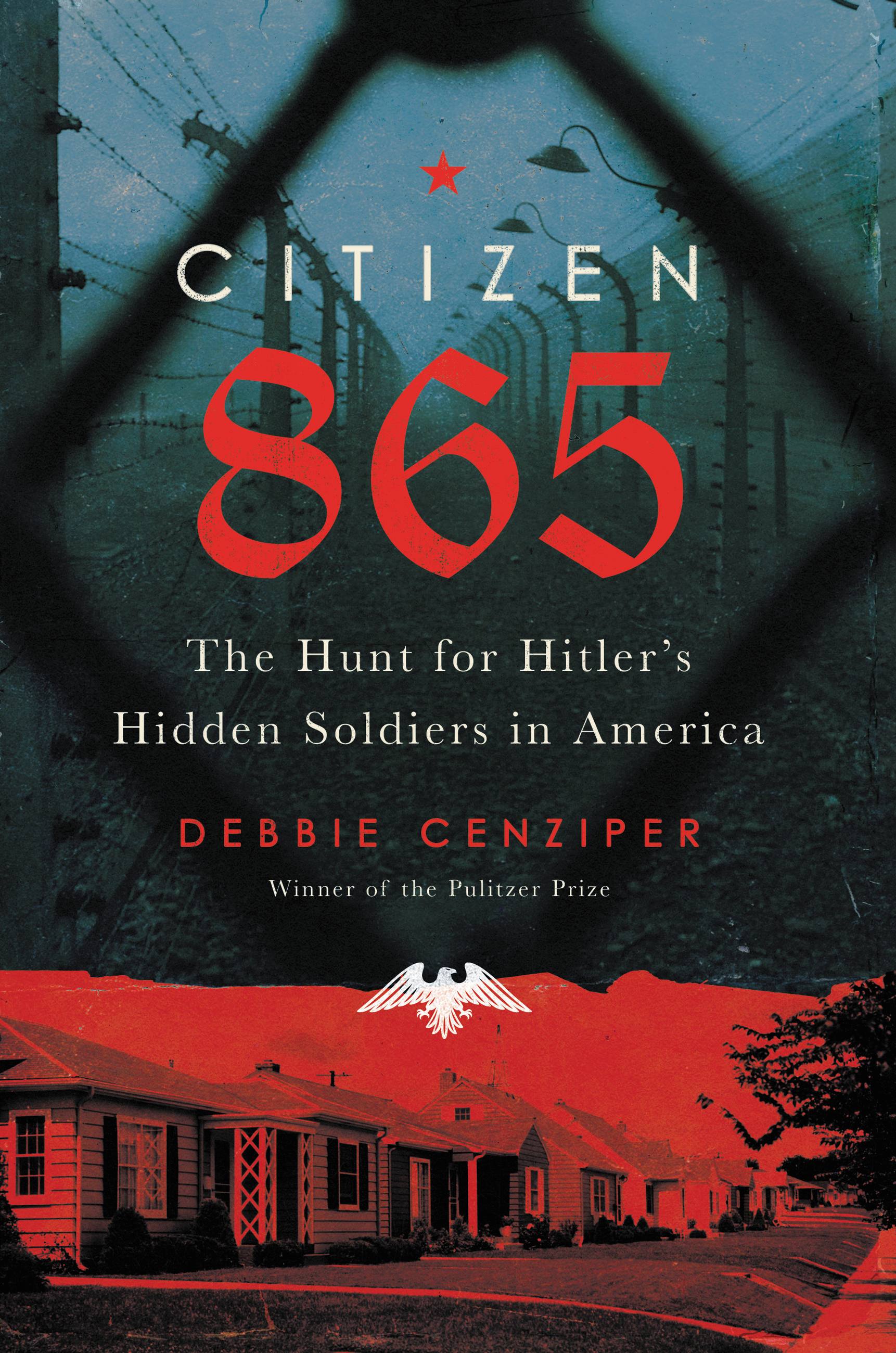

Citizen 865

The Hunt for Hitler's Hidden Soldiers in America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 12, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

**Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) Book Award Finalist**

The gripping story of a team of Nazi hunters at the U.S. Department of Justice as they raced against time to expose members of a brutal SS killing force who disappeared in America after World War Two.

In the tiny Polish village of Trawniki, the SS set up a school for mass murder and then recruited a roving army of foot soldiers, 5,000 men strong, to help annihilate the Jewish population of occupied Poland. After the war, some of these men vanished, making their way to the U.S. and blending into communities across America. Though they participated in some of the most unspeakable crimes of the Holocaust, “Trawniki Men” spent years hiding in plain sight, their terrible secrets intact.

In a story spanning seven decades, Citizen 865 chronicles the harrowing wartime journeys of two Jewish orphans from occupied Poland who outran the men of Trawniki and settled in the United States, only to learn that some of their one-time captors had followed. A tenacious team of prosecutors and historians pursued these men and, up against the forces of time and political opposition, battled to the present day to remove them from U.S. soil.

Through insider accounts and research in four countries, this urgent and powerful narrative provides a front row seat to the dramatic turn of events that allowed a small group of American Nazi hunters to hold murderous men accountable for their crimes decades after the war’s end.

Genre:

-

"This riveting saga, replete with heroes and villains, is the true story of a few good men and women who worked tenaciously to expunge an evil in our midst."George F. Will, author of The Conservative Sensibility

-

"Enriched by Debbie Cenziper's world-class investigative skills, Citizen 865 is a powerful piece of history that washes over you in waves of horror and beauty."David Maraniss, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of A Good American Family

-

"Debbie Cenziper has written a page-turning detective story about the hunt for Nazi killers living openly in neighborhoods across the United States....This is a book that anybody interested in the quest for international justice should read."Michael Isikoff, New York Times bestselling co-author of Russian Roulette: The Inside Story of Putin's War on America and the Election of Donald Trump

-

"This is a gripping tale, which reads at times like a novel. Just when you thought you knew everything about the Holocaust, we learn about the uniquely devastating role of the Trawniki training center. At a time of rising anti-Semitism, Debbie Cenziper's Citizen 865 offers a harrowing reminder of the consequences of unchecked racism and anti-Semitism. And it serves as a repository of hope-that the leadership of good men and women could bring a measure of justice to the world in the face of such overwhelming evil."Jonathan A. Greenblatt, CEO and National Director, Anti-Defamation League

-

"Citizen 865 is a great book that couldn't come at a more crucial time. In telling the story of a little-known Holocaust site called Trawniki and the people who dedicated themselves to bringing some of modern history's worst monsters to justice, Debbie Cenziper has honored the vanishing plea to never forget, first by breaking my heart with the worst of humanity, and then, with the best of us, stitching it back together."Pulitzer Prize-Winning Journalist David Finkel, author of Thank You for Your Service and The Good Soldiers

-

"Citizen 865 is a fantastic piece of detective work.... A compulsively readable story of mass murder and an epic quest by Nazi hunters to bring evil men to justice."Alex Kershaw, New York Times bestselling author of The Bedford Boys and The Longest Winter

-

"Citizen 865 reads like a thriller, but it is so much more... [It] tells an essential and unknown tale of post-war justice and the search for truth, linking the events of the Holocaust to the familiar, more recent past. Telling this story of a decades-long quest for justice is itself an act of justice. "Ariel Burger, author of Witness: Lessons from Elie Wiesel's Classroom and winner of the National Jewish Book Award in Biography

-

"Anchored in painstaking research and reporting, Citizen 865 chronicles the efforts of the lawyers and historians of the Office of Special Investigations to rid the United States of the Third Reich's mass murderers who had been hiding in plain sight. Debbie Cenziper's account vividly-and movingly-captures both the frustrations and triumphs of this extraordinary group of dedicated men and women who refused to abandon the quest for a measure of long overdue justice."Andrew Nagorski, author of 1941: The Year Germany Lost the War and The Nazi Hunters

-

"Cenziper brought her investigative skills to bear on the challenge of retrieving the hard facts, but she also possesses the gift of a storyteller....[Citizen 865 is] a highly significant work of investigation that is eye-opening and heartbreaking. She compels us to confront the crimes of the Trawniki men in a way that burns itself into both memory and history."Washington Post

-

"Skillfully written and reported....Riveting....Cenziper's account moves cinematically around in time and place."The Forward

-

"Brilliant....Intriguing....[Citizen 865 is] a powerful book and reads like a fast-paced mystery novel. But it is not fiction. It is a story and history worth reading and knowing."Jewish Exponent

-

"For Cenziper, who is Jewish, the question of delayed justice remains a key theme in the book."The Miami Herald

-

"Excellent....Well researched work of historical non-fiction reads like a fast-paced fictional thriller. [Citizen 865] provides a comprehensive and insightful presentation, not only of the painstaking work of the OSI, but also the personal lives and motivations of the attorneys and historians who staffed it."Times of Israel

-

"[Citizen 865] is serious journalism at its best....a history worth reading and knowing....a hopeful book about the power of knowing history and the rule of law."LA Review of Books

-

"A Pulitzer-worthy investigation....Debbie Cenziper provides stunning insights into these Nazi hunters' skill, accomplishments, and dedication....Passionate, provocative, and artfully constructed, this fully engaging work of deeply humanized scholarship is a fine addition to the literature of the Holocaust and its aftermath."Washington Independent Review of Books

-

"Cenziper's sophomore effort...is of vital importance....Fast-paced, well-researched, and rife with touching human details, Citizen 865 is a rarity: a thrilling work of historical nonfiction that readers will struggle to put down....Beautifully human, devoted to detail, and thoroughly enthralling...Cenziper has written a book with the power to compel its readers to honor the Holocaust's devastating history."The Federalist

-

"I have read fictional thrillers far less gripping than Citizen 865."The Charlotte Observer

-

"Gripping... [A] brisk, thrilling account."Publishers Weekly

-

"With much human interest, Cenziper draws out all the implications for principles of justice for victims and perpetrators of unspeakable crimes."Booklist (starred review)

-

"Cenziper provid[es] fascinating insight into the personalities, motivations, and procedures of the OSI prosecutors.... The accounts of Lucyna and Felix...are told with a great deal of empathy."Library Journal

- On Sale

- Nov 12, 2019

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316449663

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use