Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

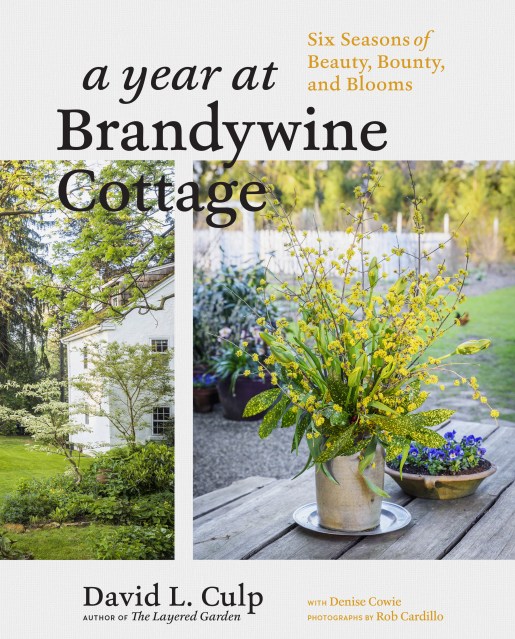

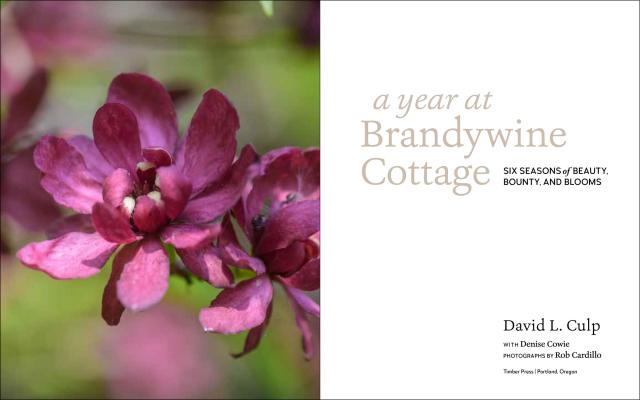

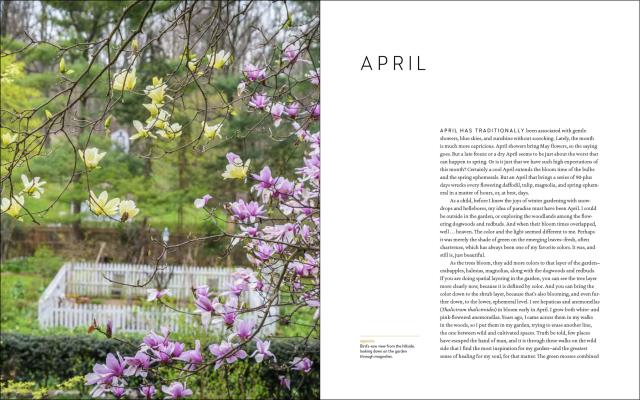

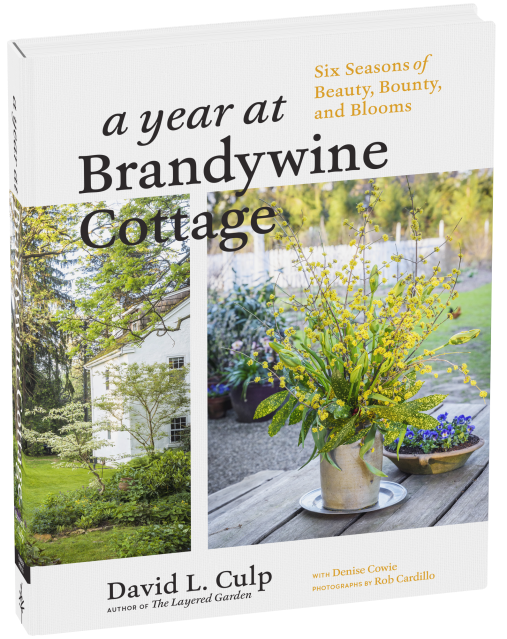

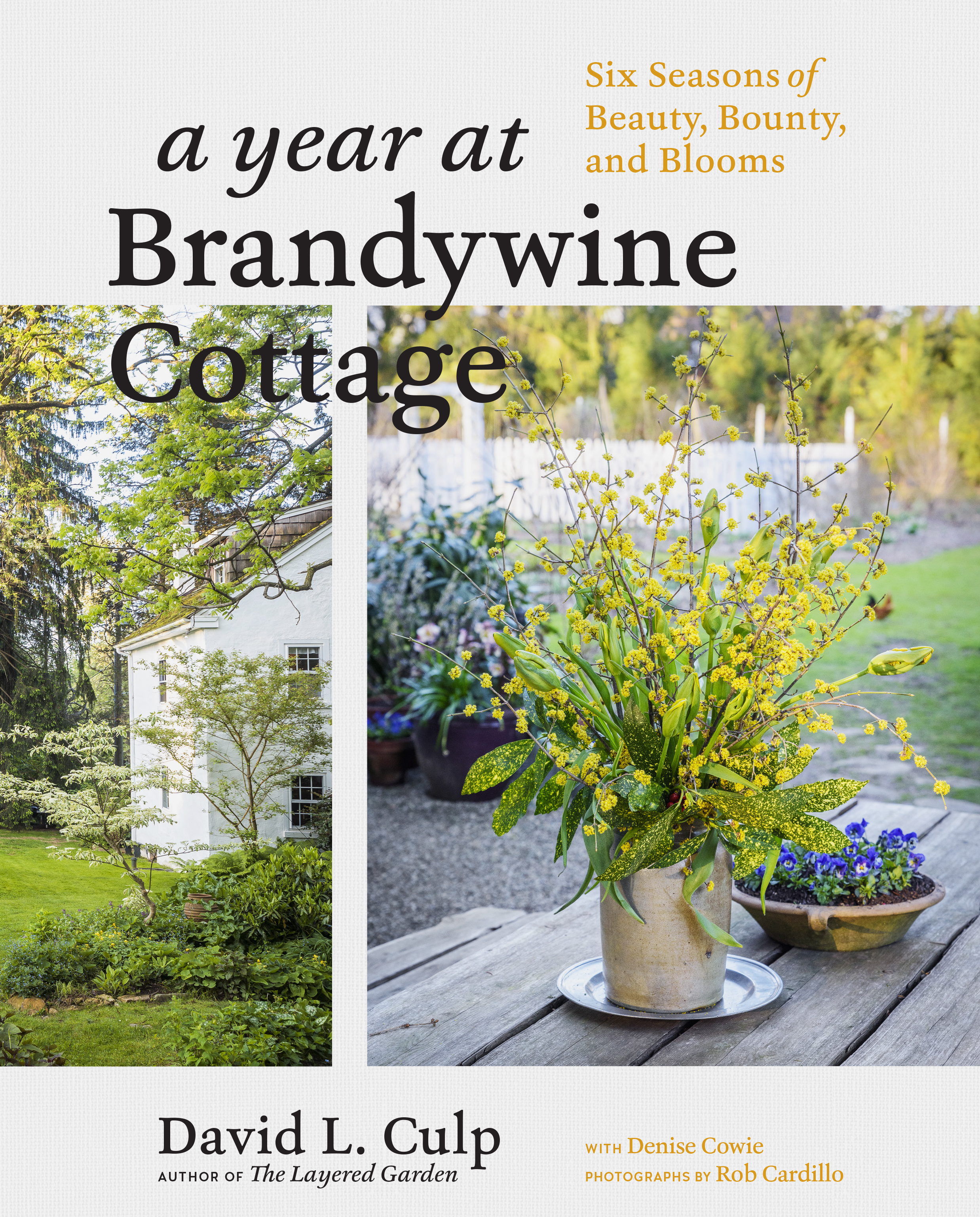

A Year at Brandywine Cottage

Six Seasons of Beauty, Bounty, and Blooms

Contributors

Photographs by Rob Cardillo

With Denise Cowie

Formats and Prices

Price

$35.00Price

$44.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 31, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“If you've been looking to be inspired by nature and everything your garden gives you, you'll be enriched by the tips and wisdom presented in this book.” —Garden Design Magazine

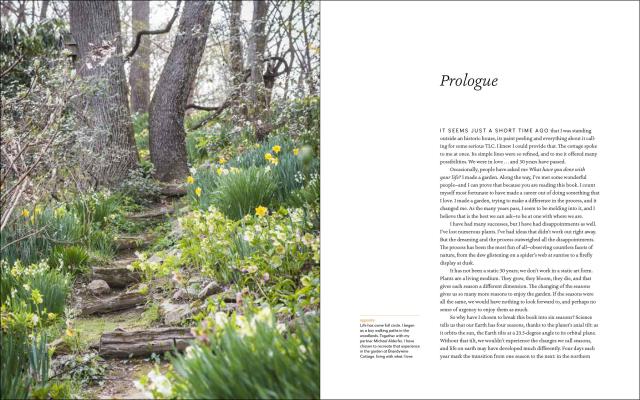

There has never been a better time to dedicate yourself to a life enriched by nature. In A Year at Brandywine Cottage, David Culp inspires you to find that connection in the comfort of your own backyard.

Organized seasonally, A Year at Brandywine Cottage is filled with fresh ideas and trusted advice on flower gardening, growing vegetables and herbs, creating simple floral arrangements, and cooking seasonally with home-grown produce. You’ll find suggested tasks for each month, including advice on when to plant and harvest, how to weed and water, and what to plant for year-round beauty.

Packed with glorious photography by Rob Cardillo and brimming with practical tips, A Year at Brandywine Cottage is your guide to living your best life in—and out—of the garden.

Genre:

-

“A Year at Brandywine Cottage is Culp’s opus, his artist’s masterpiece… not only for the seasoned gardener, but for the newbie as well. Culp offers us many pearls of wisdom.” —American Gardener

“Expect to find a new appreciation for seasonal standouts with this book, with tips on choosing and using them to best celebrate the passage of time.” —Horticulture

“This is a book to keep on your nightstand all year long… it proves you can enjoy a simple life at home with a gorgeous outdoor space no matter what the season.” —The News Tribune

“Simply spectacular… no matter what the season or weather, you can tour Brandywine Cottage through David Culp's latest book.” —Garden Design Online

“A delightful read.” —Bellwood Gardens

“If you've been looking to be inspired by nature and everything your garden gives you, you'll be enriched to learn the tips and wisdom presented in this book.” —Garden Design Magazine

“It took David Culp two years to write his book A Year at Brandywine Cottage, but more than 30 years of accumulated knowledge and devotion to produce it.” —The Washington Post

“Tells—and shows, through the beautiful images of photographer Rob Cardillo—how Culp designs, plants for, and enjoys his garden every day of the year.” —The Columbus Dispatch

“When I finished reading A Year at Brandywine Cottage, I wished it hadn’t ended. I wanted more—a sure sign of a keeper. If you are engulfed by winter doldrums, you will want to read!” —Cold Climate Gardening

- On Sale

- Mar 31, 2020

- Page Count

- 296 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781604698565

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use