Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

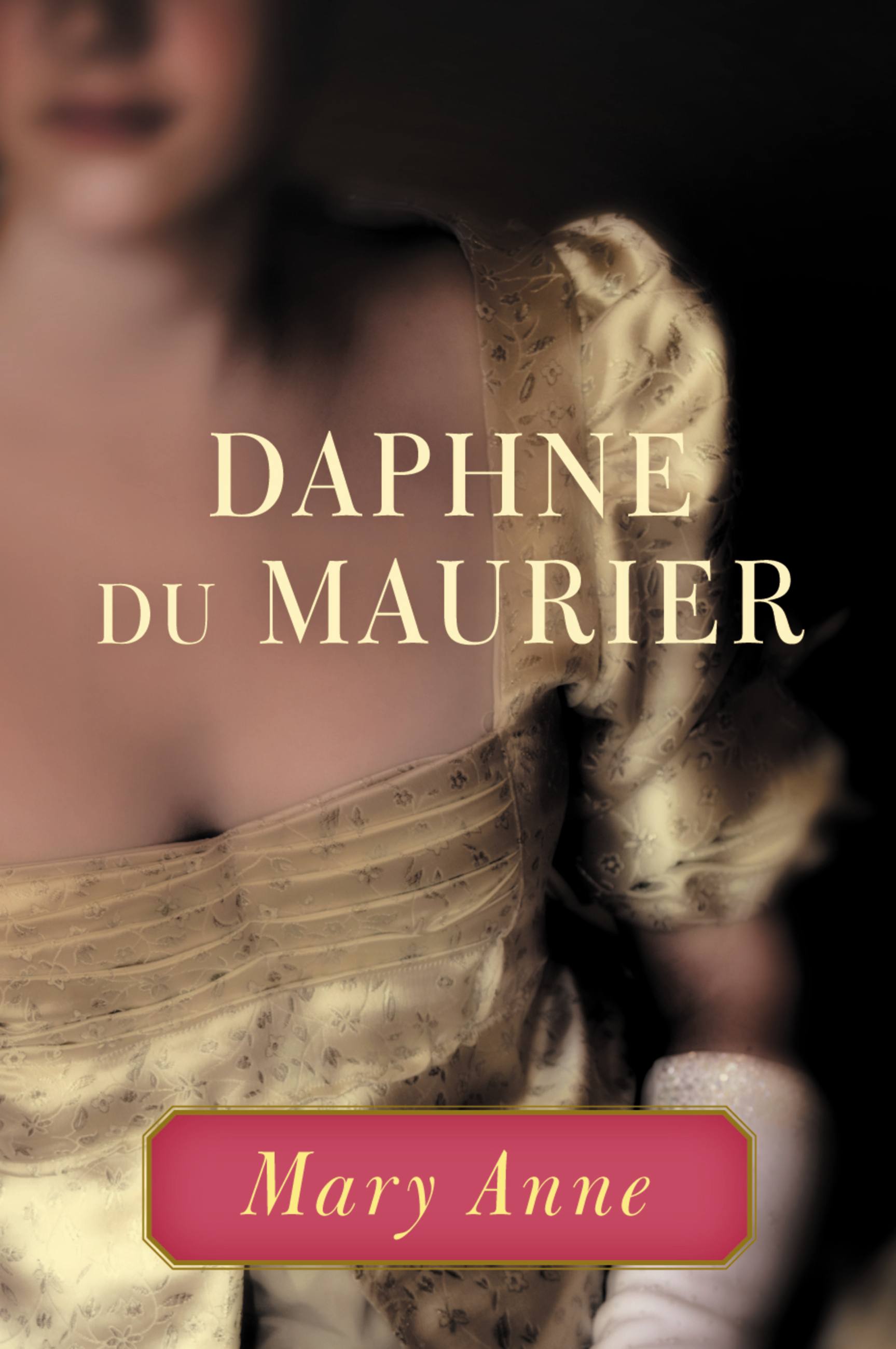

Mary Anne

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$5.99Format

Format:

- ebook (Digital original) $5.99

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 17, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

She set men’s hearts on fire and scandalized a country.

An ambitious, stunning, and seductive young woman, Mary Anne finds the single most rewarding way to rise above her station: she will become the mistress to a royal duke. In doing so, she provokes a scandal that rocks Regency England.

A vivd portrait of sex, ambition, and corruption, Mary Anne is set during the Napoleonic Wars and based on Daphne du Maurier’s own great-great-grandmother.

“This novel catches fire.”-New York Times

An ambitious, stunning, and seductive young woman, Mary Anne finds the single most rewarding way to rise above her station: she will become the mistress to a royal duke. In doing so, she provokes a scandal that rocks Regency England.

A vivd portrait of sex, ambition, and corruption, Mary Anne is set during the Napoleonic Wars and based on Daphne du Maurier’s own great-great-grandmother.

“This novel catches fire.”-New York Times

Genre:

- On Sale

- Dec 17, 2013

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316323710

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use