By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

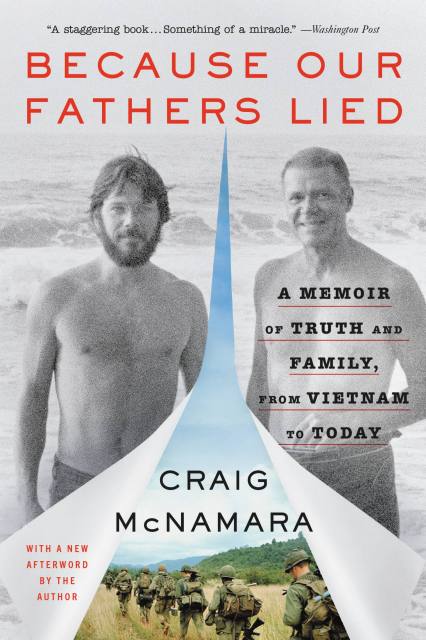

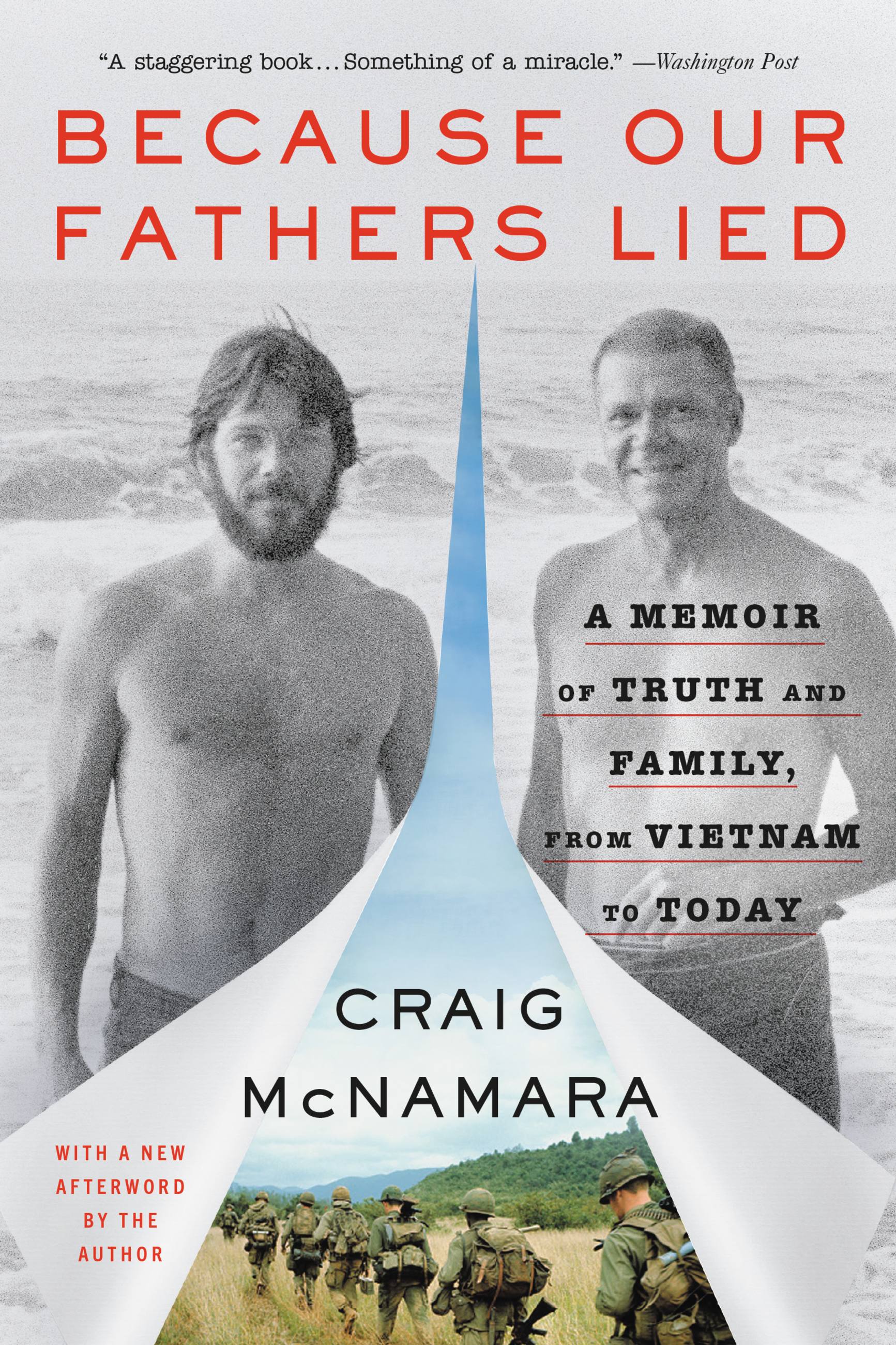

Because Our Fathers Lied

A Memoir of Truth and Family, from Vietnam to Today

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 10, 2022

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316282444

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 10, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This unforgettable father and son story confronts the legacy of the Vietnam War across two generations: “an important book that should be read by every American” (Ron Kovic, Vietnam Veteran and author of Born on the Fourth of July).

Craig McNamara came of age in the political tumult and upheaval of the late 60s. While Craig McNamara would grow up to take part in anti-war demonstrations, his father, Robert McNamara, served as John F. Kennedy's Secretary of Defense and the architect of the Vietnam War. This searching and revealing memoir offers an intimate picture of one father and son at pivotal periods in American history. Because Our Fathers Lied is more than a family story—it is a story about America.

Before Robert McNamara joined Kennedy's cabinet, he was an executive who helped turn around Ford Motor Company. Known for his tremendous competence and professionalism, McNamara came to symbolize "the best and the brightest." Craig, his youngest child and only son, struggled in his father's shadow. When he ultimately fails his draft board physical, Craig decides to travel by motorcycle across Central and South America, learning more about the art of agriculture and making what he defines as an honest living. By the book's conclusion, Craig McNamara is farming walnuts in Northern California and coming to terms with his father's legacy.

Because Our Fathers Lied tells the story of the war from the perspective of a single, unforgettable American family.

-

“Moving and courageous… a complicated man comes into intimate view, as does the ‘mixture of love and rage’ at the heart of their relationship… Through his own personal story of disappointment and disillusionment, McNamara captures an intergenerational conflict and a journey of moral identity.”Adrienne Westenfeld, Esquire

-

“McNamara’s staggeringly heartfelt debut memoir is the tale of a son’s lifelong yearning for his father to look him squarely in the eye and tell him the unvarnished truth, regardless of the scale of his missteps or regrets. In that sense it’s a universally relatable story since countless parents shield their children from hard facts and struggle to be present.”Jessica Zach, San Francisco Chronicle

-

“A captivating text for anyone grappling with the pain of possessing a parent who did horrible things… If Camelot really was a kind of court of midcentury kings, a high watermark for liberal capitalism distant from our moment of fracture, how fortunate we are to have such a thoughtful account of that world from someone who was born into it.”Noah Kulwin, New Republic

-

“That Craig McNamara has survived, and thrived, and given us this staggering book, is something of a miracle.”Joe Klein, Washington Post

-

“In a graceful, easy prose, Craig McNamara probes his shame as a son of privilege and why he gravitated toward the antiwar movement in the late 1960s."Hamilton Cain, Oprah Daily

-

“Searing… [McNamara] has made a noble effort to shed as much as possible of the pain his father bequeathed him, and the rest of our nation.”Charles Kaiser, The Guardian

-

"This is a courageous, devastating memoir, written from the inside out. While U.S. policy was conducted from an icy 30,000-ft. perch, for Craig McNamara, the Vietnam War was an intimate family drama full of complex moral dilemmas, betrayal, and family self-awareness and actualization."Ken Burns, filmmaker

-

“Because Our Fathers Lied gives readers a vivid, front-row view of the divisiveness in one very prominent family, and through that family, a view of the national divisiveness that continued long after the Vietnam War… a loving but brutally honest account of McNamara’s difficult relationship with his father.”Roger Bishop, BookPage (starred review)

-

"Behind great world tragedies are great personal tragedies. Craig McNamara has written a gripping, aching, memoir of what it was like to be the only son of a decent man with the blood of thousands on his hands."Evan Thomas, New York Times bestselling author of Ike’s Bluff: President Eisenhower’s Secret Battle to Save the World

-

“If a father’s lethal lie could be redeemed by a son who speaks the heartfelt truth, this book would do it. A poignant, crushing account that closes a circle not only for Craig McNamara, but for his generation."James Carroll, New York Times bestselling author of House of War: The Pentagon and the Disastrous Rise of American Power

-

"More than a decade after his death, Robert Strange McNamara remains one of the most compelling public figures in United States history. As Kennedy and Johnson's powerful secretary of defense, McNamara helped plunge the country into the disaster of the Vietnam War -- and in one way or another struggled during the rest of his long life to explain and redeem himself. Craig McNamara's memoir, Because Our Fathers Lied, is a painfully honest and uncompromising quest to come to grips with his relationship with his father -- and to disentangle the complex ties between love and political truth."Mark Danner, author of Spiral: Trapped in the Forever War

-

"Craig McNamara has written an important book that should be read by every American if we are ever to truly heal from that war."Ron Kovic, Vietnam Veteran and author of Born on the Fourth of July

-

“Craig McNamara has written a courageous and moving memoir about his fractured relationship with his father, Robert McNamara, a microcosm of the heartbreaking divisions that sundered the nation during the Vietnam War. It is an unsparingly honest account about father and son, a powerful story of love, loss and resilience that sheds new light on one of the most convulsive periods in American history.”Philip Taubman, former New York Times Washington bureau chief and Moscow bureau chief

-

“Robert McNamara's lies about Vietnam not only ruptured a nation, they tore at the heart of his young, sensitive son, animating his journey from dark legacy to a life of purpose. Because Our Fathers Lied is a deeply moving tale about a singular relationship as unresolved as the war itself.”Garry Trudeau, creator of Doonesbury

-

“Craig McNamara has written an intimate personal story about the afterlife of America’s disastrous Vietnam experience. His attempts to understand his own father, one of the most controversial figures of the 20th century, have created a new chapter in that history. His voice is as morally focused as any that resisted the war.”Daniel Ellsberg

-

"Like the farmer willing to labor another season, searching for one more harvest, Craig McNamara invites us into a rare conversation about history that defines us as he explores loss while caring about the meaning of family - a son's struggle with a father and the shadow of Viet Nam."David Mas Masumoto, organic farmer and author of Wisdom of the Last Farmer: Harvesting Legacies from the Land

-

“Anyone who lived through the sixties remembers the Vietnam War, Robert McNamara, and the intensity of feelings about the role he played in the prosecution of that war. Indeed, rightly or wrongly, it became known as McNamara's War…This is a story — an unknown story — about their [Robert and Craig’s] relationship and how the hurt of the conflict in Vietnam, a national sorrow, spilled over into a personal relationship…A story about a generational conflict as well as an international conflict, and an important book in our understanding of that now-distant era.”Errol Morris, director of The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara

-

"This memoir is both fascinating and heartbreaking. Craig McNamara has taken the monumental figure of his father, Robert McNamara, and brings him to life in a profoundly intimate way. This is not just a beautifully written book about the past history of our country, it tells an urgent story about the present. Through the experiences of his becoming an activist and travelling the world, we deeply understand Craig's passionate commitment to equity and sustainability.”Alice Waters, author of Coming to My Senses

-

“Craig McNamara, in this heartfelt memoir, shares the story of his coming of age, haunted by the horrors of the Vietnam War and his father's role in it. Hobnobbing at the White House, war protesting in Berkeley, motorcycling to Chile and even living on Easter Island, then becoming a walnut farmer in Northern California—McNamara recounts an absorbing tale of father and son, bound together but deeply separated by different lives and understandings of truth and loyalty. The telling is clear and candid.”Jerry Brown

-

“Craig McNamara has given us a profound, wrenching, brave, and essential memoir – a must read for anyone who wants to understand the tragedy of the Vietnam War and why its echoes are still being felt in America today. He carries the painful burden of being the son of Robert McNamara -- architect of a war he knew at the time was unwinnable -- with tremendous grace. Craig’s humanity, generosity of spirit, and compassion come through on every page of this intimate, devastating and revelatory journey into a dark time of promises broken, illusions shattered, lives lost.”Lynn Novick, co-director and producer of The Vietnam War

-

“Craig McNamara’s memoir is an emotional revelation from a tragic time in history with many parallels to the present. Despite the painfully felt influence of his father, Craig has preserved in these pages a hopeful and loving vision of life. This is a moving, remarkable book.”Rose Styron

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use