By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

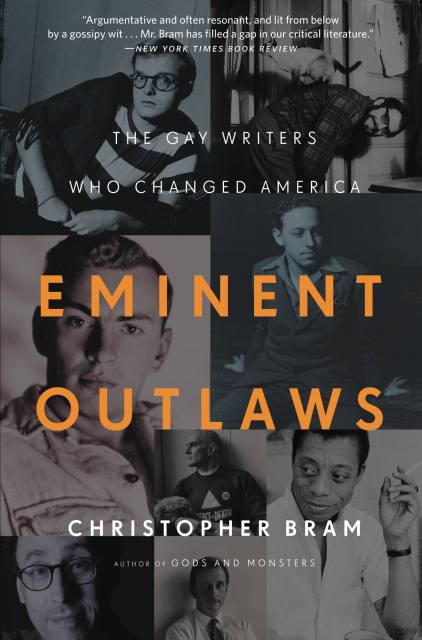

Eminent Outlaws

The Gay Writers Who Changed America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$18.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 2, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This “standard text of the defining era of gay literati” tells the cultural history of the interconnected lives of the 20th century's most influential gay writers (Philadelphia Inquirer).

In the years following World War II a group of gay writers established themselves as major cultural figures in American life. Truman Capote, the enfant terrible, whose finely wrought fiction and nonfiction captured the nation's imagination. Gore Vidal, the wry, withering chronicler of politics, sex, and history. Tennessee Williams, whose powerful plays rocketed him to the top of the American theater. James Baldwin, the harrowingly perceptive novelist and social critic. Christopher Isherwood, the English novelist who became a thoroughly American novelist. And the exuberant Allen Ginsberg, whose poetry defied censorship and exploded minds. Together, their writing introduced America to gay experience and sensibility, and changed our literary culture.

But the change was only beginning. A new generation of gay writers followed, taking more risks and writing about their sexuality more openly. Edward Albee brought his prickly iconoclasm to the American theater. Edmund White laid bare his own life in stylized, autobiographical works. Armistead Maupin wove a rich tapestry of the counterculture, queer and straight. Mart Crowley brought gay men's lives out of the closet and onto the stage. And Tony Kushner took them beyond the stage, to the center of American ideas.

With authority and humor, Christopher Bram weaves these men's ambitions, affairs, feuds, loves, and appetites into a single sweeping narrative. Chronicling over fifty years of momentous change-from civil rights to Stonewall to AIDS and beyond.

Eminent Outlaws is an inspiring, illuminating tale: one that reveals how the lives of these men are crucial to understanding the social and cultural history of the American twentieth century.

In the years following World War II a group of gay writers established themselves as major cultural figures in American life. Truman Capote, the enfant terrible, whose finely wrought fiction and nonfiction captured the nation's imagination. Gore Vidal, the wry, withering chronicler of politics, sex, and history. Tennessee Williams, whose powerful plays rocketed him to the top of the American theater. James Baldwin, the harrowingly perceptive novelist and social critic. Christopher Isherwood, the English novelist who became a thoroughly American novelist. And the exuberant Allen Ginsberg, whose poetry defied censorship and exploded minds. Together, their writing introduced America to gay experience and sensibility, and changed our literary culture.

But the change was only beginning. A new generation of gay writers followed, taking more risks and writing about their sexuality more openly. Edward Albee brought his prickly iconoclasm to the American theater. Edmund White laid bare his own life in stylized, autobiographical works. Armistead Maupin wove a rich tapestry of the counterculture, queer and straight. Mart Crowley brought gay men's lives out of the closet and onto the stage. And Tony Kushner took them beyond the stage, to the center of American ideas.

With authority and humor, Christopher Bram weaves these men's ambitions, affairs, feuds, loves, and appetites into a single sweeping narrative. Chronicling over fifty years of momentous change-from civil rights to Stonewall to AIDS and beyond.

Eminent Outlaws is an inspiring, illuminating tale: one that reveals how the lives of these men are crucial to understanding the social and cultural history of the American twentieth century.

- On Sale

- Feb 2, 2012

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9780446575980

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use