Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

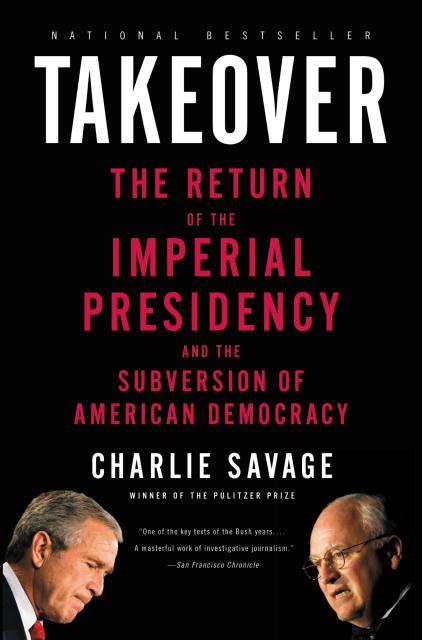

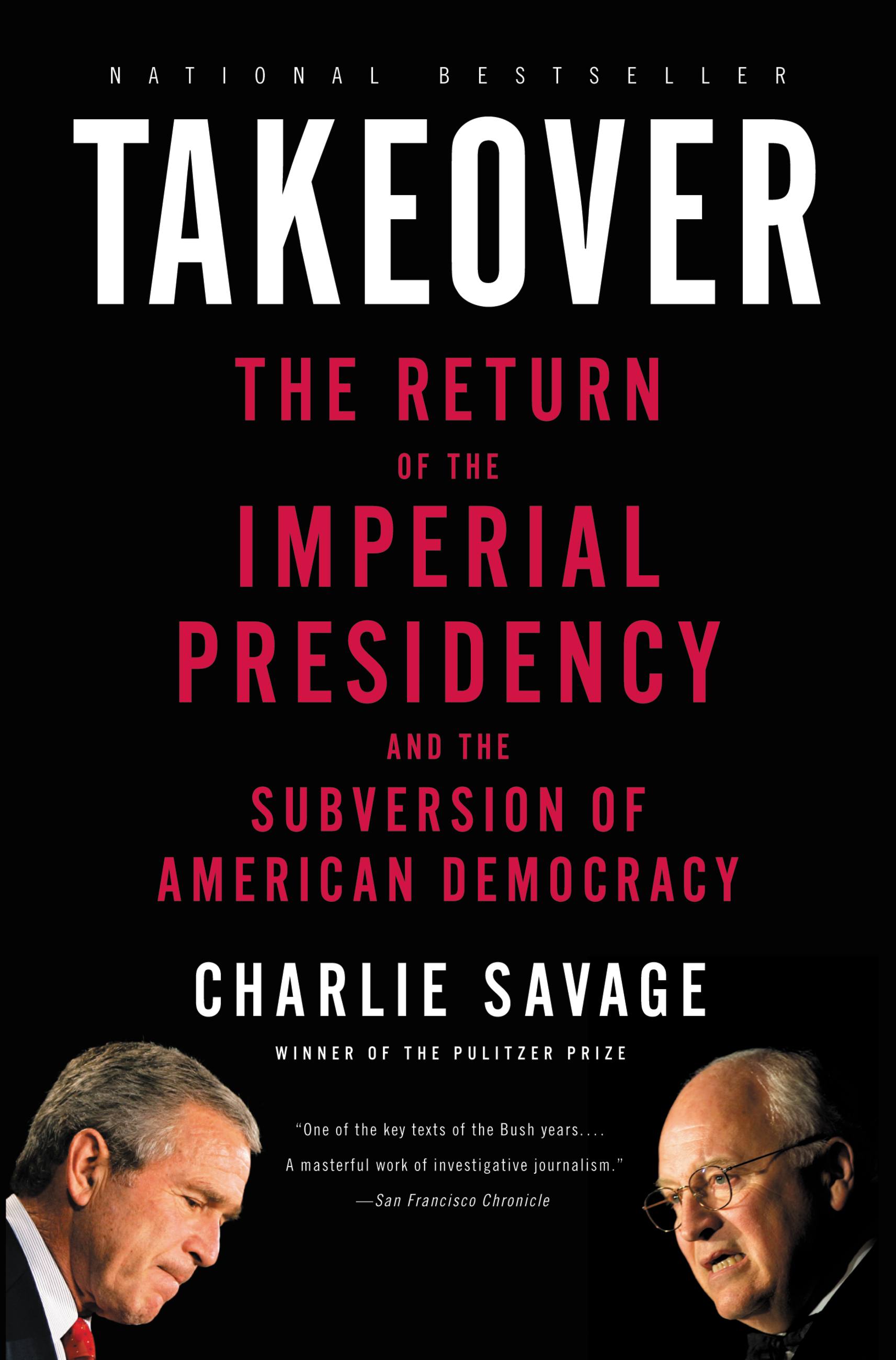

Takeover

The Return of the Imperial Presidency and the Subversion of American Democracy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 5, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In 1789, the Founding Fathers came up with a system of checks and balances to keep kingly powers out of the hands of American presidents. But in the 1970s and ’80s, a faction of Republican loyalists, outraged by the fall of the imperial presidency after Watergate and the Vietnam War, abandoned conservatives’ traditional suspicion of concentrated government power. These men hatched a plot that would allow the White House to return to, or even surpass, the virtually unchecked powers that Richard Nixon had briefly tried to wield. Congress would be defanged, and the commander-in-chief would be able to assert a unilateral dominance both at home and abroad.

Today, this plot is coming to fruition. As Takeover reveals, the Bush-Cheney administration has succeeded in seizing vast powers for the presidency by throwing off many of the restraints placed upon it by Congress, the courts, and the Constitution. This timely book unveils the secret machinations behind the headlines, explaining the links between warrantless wiretapping and the President Bush’s Supreme Court nominees, between the torture debate and the secrecy surrounding Vice President Cheney’s energy task force, and between the “faith-based initiative” and the holding of US citizens without trial as “enemy combatants.” It tells, for the first time, the full story of a hidden agenda three decades in the making, laying out how a group of true believers set out to establish monarchical executive powers that, in the words of one conservative critic, “will lie around like a loaded weapon” ready to be picked up by any future president.

Brilliantly reported and deftly told, Takeover is a searing investigation into how the constitutional balance of our democracy is in danger of being permanently altered. For anyone who cares about America’s past, present, and future, it is essential reading.

Today, this plot is coming to fruition. As Takeover reveals, the Bush-Cheney administration has succeeded in seizing vast powers for the presidency by throwing off many of the restraints placed upon it by Congress, the courts, and the Constitution. This timely book unveils the secret machinations behind the headlines, explaining the links between warrantless wiretapping and the President Bush’s Supreme Court nominees, between the torture debate and the secrecy surrounding Vice President Cheney’s energy task force, and between the “faith-based initiative” and the holding of US citizens without trial as “enemy combatants.” It tells, for the first time, the full story of a hidden agenda three decades in the making, laying out how a group of true believers set out to establish monarchical executive powers that, in the words of one conservative critic, “will lie around like a loaded weapon” ready to be picked up by any future president.

Brilliantly reported and deftly told, Takeover is a searing investigation into how the constitutional balance of our democracy is in danger of being permanently altered. For anyone who cares about America’s past, present, and future, it is essential reading.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 5, 2007

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316019613

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use