Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

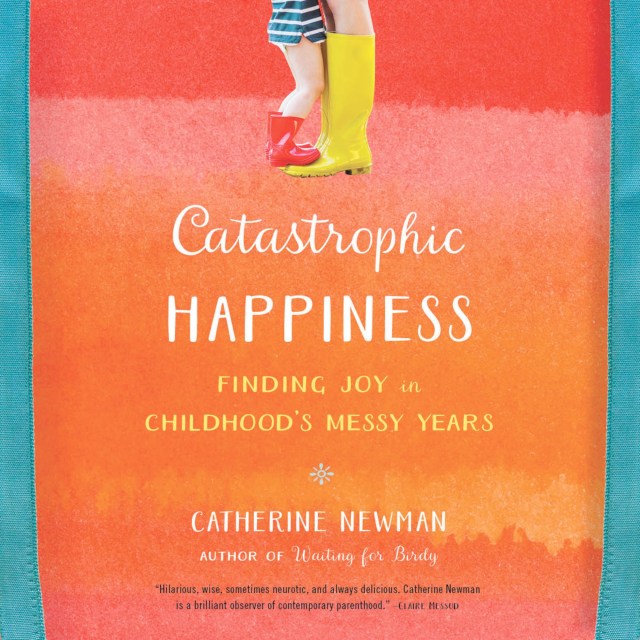

Catastrophic Happiness

Finding Joy in Childhood's Messy Years

Contributors

Read by Catherine Newman

Formats and Prices

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 5, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A comic and heartwarming memoir about childhood’s second act from Real Simple journalist Catherine Newman.

Much is written about a child’s infancy and toddler years, which is good since children will never remember it themselves. It is ages 4-14 that make up the second act, as Catherine Newman puts it in this delightfully candid, outlandishly funny new memoir about the years that “your children will remember as childhood.”

Following Newman’s son and daughter as they blossom from preschoolers into teenagers, Catastrophic Happiness is about the bittersweet joy of raising children — and the ever-evolving landscape of issues parents traverse. In a laugh out-loud, heart-wrenching, relatable voice, Newman narrates events as momentous as grief and as quietly moving as the moonlit face of a sleeping child.

From tantrums and friendship to fear and even sex, Newman’s fresh take will appeal to any parent riding this same roller coaster of laughter and heartbreak.

Much is written about a child’s infancy and toddler years, which is good since children will never remember it themselves. It is ages 4-14 that make up the second act, as Catherine Newman puts it in this delightfully candid, outlandishly funny new memoir about the years that “your children will remember as childhood.”

Following Newman’s son and daughter as they blossom from preschoolers into teenagers, Catastrophic Happiness is about the bittersweet joy of raising children — and the ever-evolving landscape of issues parents traverse. In a laugh out-loud, heart-wrenching, relatable voice, Newman narrates events as momentous as grief and as quietly moving as the moonlit face of a sleeping child.

From tantrums and friendship to fear and even sex, Newman’s fresh take will appeal to any parent riding this same roller coaster of laughter and heartbreak.

Genre:

-

Praise for Catastrophic HappinessElissa Strauss, New York Times Book Review

"Ultimately the most fascinating character isn't her family, but Newman herself. This is because the book's force lies not in what it tells us about parenting, but in its sensitive portrayal of the blurring of self that happens after one has children. . . For Newman, this question of where she begins and ends is less of a riddle than a Buddhist koan. Wisely, she never tries to solve it. Her goal, in parenting and in writing, is only to figure out how to love from within it." -

"Part of what makes Ms. Newman so good is her butterfly prose, colorful and light on its feet; part of it is her marvelous ability to reassure. It's affirming for parents to see their lives reflected back at them, and in a theme-park fun house no less, with all of the dreary bits made stretchy and silly. I adore her sideways sense of humor."Jennifer Senior, New York Times

-

"In writing that comes close to poetry, Newman really does manage to capture this bittersweet side of parenting, without overemphasizing either the bitter or the sweet. It's the two together that epitomize the job of raising and loving people who are destined to grow up and leave you, and her ability to see this that makes this book so uniquely good."Malena Watrous, San Francisco Chronicle

-

"This is a book about mothers and children, or really, about how the job of mothering changes a woman, inevitably, irrevocably, and sometimes uncomfortably. Newman's self-awareness is what makes the book work; it's a portrait of striving toward a perfection that never existed, while loving the imperfection that surrounds us."Kate Tuttle, Boston Globe

-

"Winsome and funny."People Magazine

-

"An intimate account about the hectic joy of raising children and embracing the silver lining of all those inevitable hair-pulling-out mom moments."Glamour.com

-

"Catastrophic Happiness celebrates the absurdly lovely mess of the parenting years."More

-

"You know those taunting posts that promise to make you "feel all the feels" only to leave you annoyed and let down? This is not one of those times. Catherine Newman's new essay collection on raising her two kids will make you laugh, cry, worry with her, and wish that you could make even the messiest, hardest, most crazy-making days with your children last just a little bit longer."FamilyFun

-

"Newman's stories are specific and funny, and she writes about the gamut of emotions we feel but can't always verbalize for ourselves. (She) takes her readers along for a fascinating, yet comfortingly familiar, ride of family life."Kristen Kemp, Parents Magazine

-

"A series of essays, which masterfully combine story and reflection...Newman's observations run the gamut from deep and profound to hilarious and true. Newman has a true gift for making the reader feel intimately connected to her family. In Catastrophic Happiness Newman has trapped lightning in a jar, allowing us all to admire its dazzle. In her book's short, lovely pages she captures life as a mother, life as a human being, life in general, in all of its gorgeous, complicated grandeur."Lindsey Mead, Brain, Child

-

"Laugh-out-loud funny. Newman brings tears and laughter and truth to the inexplicable-like the demanding aimlessness of her children's stories-pairing some very effective anecdotes with the boredom, pride, disgust, and joy of child-rearing."Publishers Weekly

-

"Hilarious, wise, sometimes neurotic and always delicious. Catherine Newman is a brilliant observer of contemporary parenthood."Claire Messud

-

"I've already read most of this book twice because that's the kind of book it is. You pick it up for laughs at the end of a long day and before you fall asleep, there are tears in your eyes. Your husband looks at you funny and you tell him, 'Yes I'm reading it again.' If you are a parent, this is the book you need to read."Cammie McGovern, author of Say What You Will and A Step Towards Falling

-

"Our generation's 'Poet Laureate of Parenthood'....There is no one else who reports from the parenting trenches better than Catherine Newman. Everything that makes raising kids so wonderfully unforgettable is here--the exhaustion, the hilarity, the fear, the self-doubt, the sweetness. Especially the sweetness. Even though she sugarcoats nothing--that's what sticks."Jenny Rosenstrach, blogger and author of Dinner, A Love Story

-

"Catastrophic Happiness unearthed all the moments I forgot to remember, things I meant to write down and preserve before they faded. As I read, I smiled and nodded, reliving, through Newman's heartbreakingly beautiful prose, the most golden--and the most gruesome--moments of my parenting life."Jessica Lahey, author of New York Times bestseller The Gift of Failure

-

"You know how parenting books don't actually really help? Catherine Newman's book is the opposite. Totally personal and weirdly relatable, it soothes, inspires, and fascinates me. She manages to make me LOL and want to run upstairs and smell the heads of my sleeping children."Kate Schatz, New York Times bestselling author of Rad American Women A-Z and Rid of Me, A Story

-

"A gorgeous love letter to parenting. Nobody beats Catherine Newman for cracking you up while breaking your heart--and somehow teaching the wise things you always meant to learn along the way."Katherine Center, author of Happiness for Beginners

-

"Catherine Newman could write about watching paint dry and manage to be both funny and profound. Her musings on motherhood and its attendant heartbreak will have you laughing out loud, nodding gratefully in agreement, and grasping for a Kleenex. There's no other writer I want accompanying me through my own journey in mothering."Luisa Weiss, author of My Berlin Kitchen and founder of The Wednesday Chef

-

"I was reluctant to relive early parenting, but from the first sentence, Catastrophic Happiness had me on the verge of tears and laughter. But honestly, Catherine Newman could write about the black mold that lines my kitchen sink and I would be captivated and moved. She is that awesome of a writer. I pray that she writes about teenagers, menopause, and old age, because I will be right there with her, ready for her words to help me through."Phyllis Grant, author of the Dash and Bella blog

-

"The poignancy, mania, and hilarity of parenthood drenches this delicious book. Catherine Newman divulges more than her own maternal peaks and valleys-- she offers us a way of looking at our own precious day-to-day. This book is flat-out honest, and it teems with humor and sweetness."Amity Gaige, author of Schroder

-

"Catastrophic Happiness is everything I could have hoped it might be. Reading it, I kept wanting to throw a fist in the air and scream, THANK YOU CATHERINE! I had the strangest and most wonderful feeling that she had climbed inside my head and knew exactly what I needed to hear."Molly Wizenberg, author of Orangette blog and the books A Homemade Life and Delancey

- On Sale

- Apr 5, 2016

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478957010

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use