Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

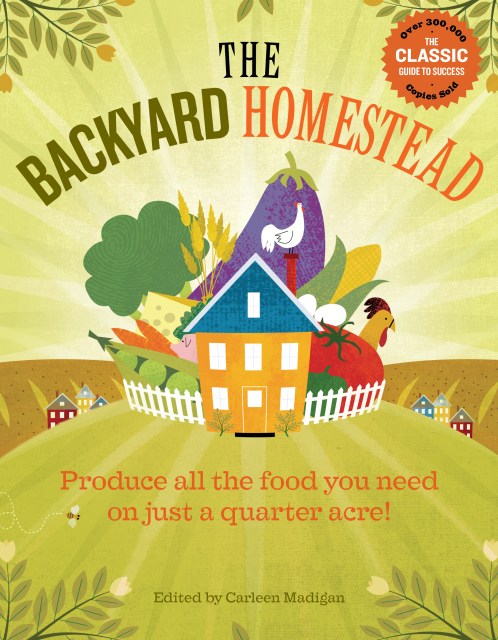

The Backyard Homestead

Produce all the food you need on just a quarter acre!

Contributors

Edited by Carleen Madigan

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 11, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This comprehensive guide to homesteading provides all the information you need to grow and preserve a sustainable harvest of grains and vegetables; raise animals for meat, eggs, and dairy; and keep honey bees for your sweeter days. With easy-to-follow instructions on canning, drying, and pickling, you’ll enjoy your backyard bounty all winter long.

Also available in this series: The Backyard Homestead Seasonal Planner, The Backyard Homestead Book of Building Projects, The Backyard Homestead Guide to Raising Farm Animals, and The Backyard Homestead Book of Kitchen Know-How.

This publication conforms to the EPUB Accessibility specification at WCAG 2.0 Level AA.

Also available in this series: The Backyard Homestead Seasonal Planner, The Backyard Homestead Book of Building Projects, The Backyard Homestead Guide to Raising Farm Animals, and The Backyard Homestead Book of Kitchen Know-How.

This publication conforms to the EPUB Accessibility specification at WCAG 2.0 Level AA.

Genre:

-

"Bottom line is, even if you're not ready for complete self-sufficiency, in today's economic climate, it just makes sense to try to produce some of your own food. And this book is a great way to get your feet wet."Bust

-

"The tone is sweet and accessible, and the well-organized chapters cover all the bases…” — July 2009Everyday Prepper

-

“This book delivers what it aims to sell. Its 368 pages of information on creating a successful, self sufficient, backyard homestead that will keep you and your family busy and eating all year long. 4.5 out of five stars, this is the book homestead enthusiasts have been looking for. Go buy this book!”Boston Sunday Globe

-

“The Backyard Homestead is a comprehensive and accessible guide to starting a vegetable garden, raising chickens and cows, canning food, making cheese, and a whole lot more. Editor Carleen Madigan…a homesteader in her own right, draws on the dozens of books about country living that Storey has published since its founding in 1983.”New York Times Book Review

-

“Because you need to brace yourself for what’s on the horizon: The Backyard Homestead. This fascinating, friendly book is brimming with ideas, illustrations, and enthusiasm. The garden plans are solid, the advice crisp; the diagrams, as on pruning and double digging, are models of decorum. Halfway through, she puts the pedal to the metal, and whoosh! At warp speed, we’re growing our own hops and making our own beer, planting our own wheat fields, keeping chickens (ho hum), ducks, geese, and turkeys (now we’re talking) and milking goats, butchering lamb, raising rabbits, and grinding sausage. Oh, and tapping our maple trees, churning butter, and making our own cheese and yogurt. Peacocks, anyone? Need I say more? Well, yes. Stock up on some knitting books because next winter, you’ll want to grow your own sweaters, too."

- On Sale

- Feb 11, 2009

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9781603425148

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use