Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

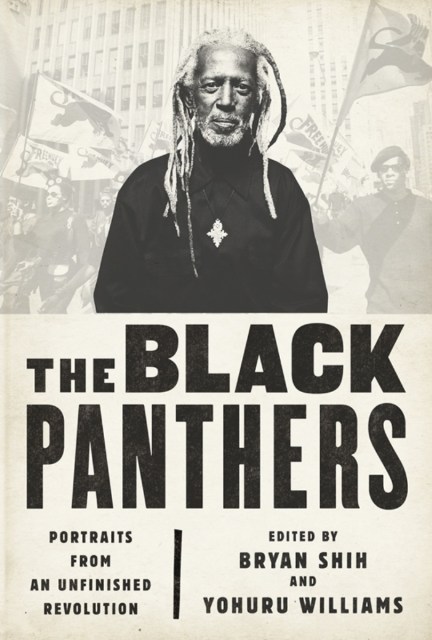

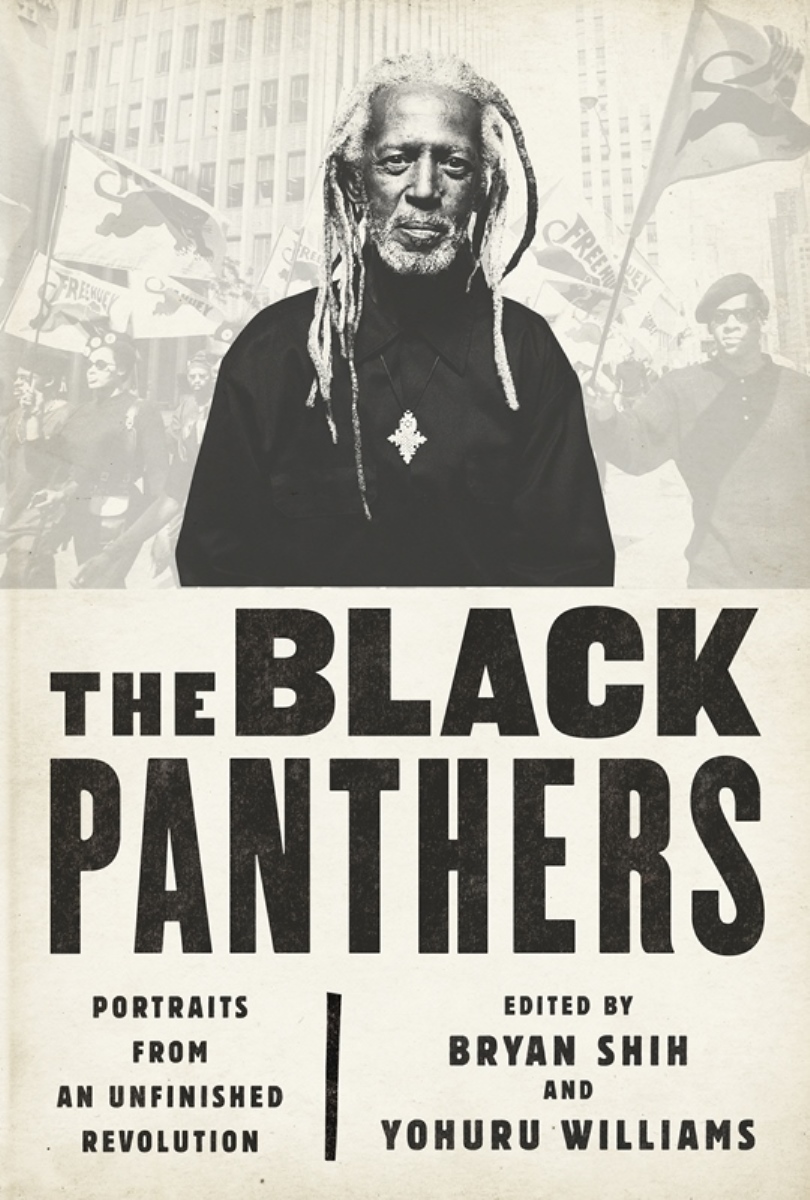

The Black Panthers

Portraits from an Unfinished Revolution

Contributors

By Bryan Shih

Introduction by Peniel E. Joseph

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $20.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 13, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“A brilliantly conceived volume. Bryan Shih and Yohuru Williams demonstrate why the Panthers’ story-its lessons and failures-even fifty years after its founding remains key to understanding national and international struggles for freedom and justice today.” — Cheryl Finley, professor and director of visual studies, Cornell University

Even fifty years after it was founded, the Black Panther Party remains one of the most misunderstood political organizations of the twentieth century. But beyond the labels of “extremist” and “violent” that have marked the party, and beyond charismatic leaders like Huey Newton, Bobby Seale, and Eldridge Cleaver, were the ordinary men and women who made up the Panther rank and file.

In The Black Panthers, photojournalist Bryan Shih and historian Yohuru Williams offer a reappraisal of the party’s history and legacy. Through stunning portraits and interviews with surviving Panthers, as well as illuminating essays by leading scholars, The Black Panthers reveals party members’ grit and battle scars-and the undying love for the people that kept them going.

-

"The Black Panthers succeeds by destroying any assumptions you may have had [about the Black Panther Party]. The book tells the story of the Black Panthers through first-person accounts from people who were part of the movement but who mostly were not the stars-people who look like they could be my aunts and uncles...[It] does the much needed task of bringing the movement down to earth."Rembert Browne, New York Times Book Review

-

"Shih's powerful black-and-white portraits...are by turn-and sometimes all at once-bold, unflinching, poetic, familiar, cloaked, direct, joyful, defiant, mischievous and suspicious....To many readers, these stories of nascent revolution and service will be enlightening, even eye-opening, giving a new view of an organization that was vilified, feared and opposed in history and the press. For others, they are a reminder of a time when black organizers and other people of color declared an unstinting willingness to improve their communities and radically change the trajectory of their people's lives."Tina McElroy Ansa, Washington Post

-

"While no doubt rooted in the past, Portraits from an Unfinished Revolution focuses squarely on the present, with portraits and interviews with former members today. While the authors did an excellent job of tracking down higher-ups in the party, the book smartly turns its focus to the 'real heroes,' the group's rank-and-file members, giving us a fuller picture of life as a Black Panther, and the impact those years had on people's lives... A well-rounded primer on the Black Panther Party, then and now, top to bottom."Mother Jones

-

"A brilliantly conceived volume that offers a refreshing take on a well-trod history too often told from the perspective of its Oakland-based, male leaders and their iconic images. Uniquely, this powerful book is driven by Bryan Shih's recent portraits of local chapter rank-and-file members, whose gripping recollections told in oral histories illuminate the complexity and importance of the BPP's grassroots organizing structure in history and for our own times. This innovative volume boasts a remarkable series of essays by leading scholars on a range of topics including Black Power, women, the rank-and-file, ethnic nationalism, health activism and international outreach as well as a treasure trove of archival images from the Black Panther Newspaper. Together, Bryan Shih and Yohuru Williams demonstrate why the Panthers story-its lessons and failures-even fifty years after its founding, remains key to understanding national and international struggles for freedom and justice today."Cheryl Finley, Associate Professor and Director of Visual Studies, Cornell University

-

"An hypnotic reflection pool on the movement, the mythologies, and the women and men who challenged oppression as no other organization made in America ever had before. Brilliant, painful, enlightening, tearful, tragic, sad, and funny, this photo-essay book is at its core about healing, and about the social justice work that still needs to be done in the era of hip-hop, Black Lives Matter, and the historic presidency of Barack Obama."Kevin Powell, author of The Education of Kevin Powell: A Boy's Journey into Manhood

-

"During our moment of Black Lives Matter on the one hand and Trump-enabled open racism and hatred on the other, connecting to the stories of a previous generation of activists feels vital, and in these portraits, quite stunning."Flavorwire

-

"An eye-opening experience...Reading The Black Panthers has changed a lot for me. The photos, the essays, the information found in this volume have now made my education on the Party paramount. Their movement will now be part of my activism, their fight, which sadly still rages on, is my fight."Dan Arel, Patheos

-

"Fifty years [since the party's founding], photojournalist Shih and historian Williams observe that the party remains 'one of the most misunderstood organizations of the twentieth century.' To dispel this fog, they met with 45 surviving rank-and-file members, men and women who went on to become teachers, professors, attorneys, elected officials, founders and directors of not-for-profit organizations, and artists. Each is present here in striking photographic portraits and revelatory oral histories...Incisive essays provide a larger historical context."Booklist, Starred Review

-

"With a splendid assemblage of pictures and interviews, photographer Shih and historian Williams shine fresh light on the people in and the diverse activities of the Black Panther Party (BPP) on the 50th anniversary of its founding. Shih's photographs of the 45 interviewees have the vibrancy and immediacy of treasured family portraits. The interviewees' compelling recollections are buttressed by succinct but substantive essays...The special virtue of this book is as bottom-up, rather than top-down, history-an illuminating view of the everyday aspects of 'one of the most misunderstood organizations of the 20th century.'"Publishers Weekly, "Most Anticipated Books for Fall 2016"

-

"This highly recommended compilation of interviews and photographs of the Black Panther Party helps reframe its legacy to include the humanitarian work they performed across the United States. Readers interested in the current Black Lives Matter movement will find resonance in the Panthers' stories."Library Journal

-

"An intelligent, unapologetic book."Shelf Awareness

-

"An interesting celebration of a unique era's activism."Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- Sep 13, 2016

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568585567

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use