Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

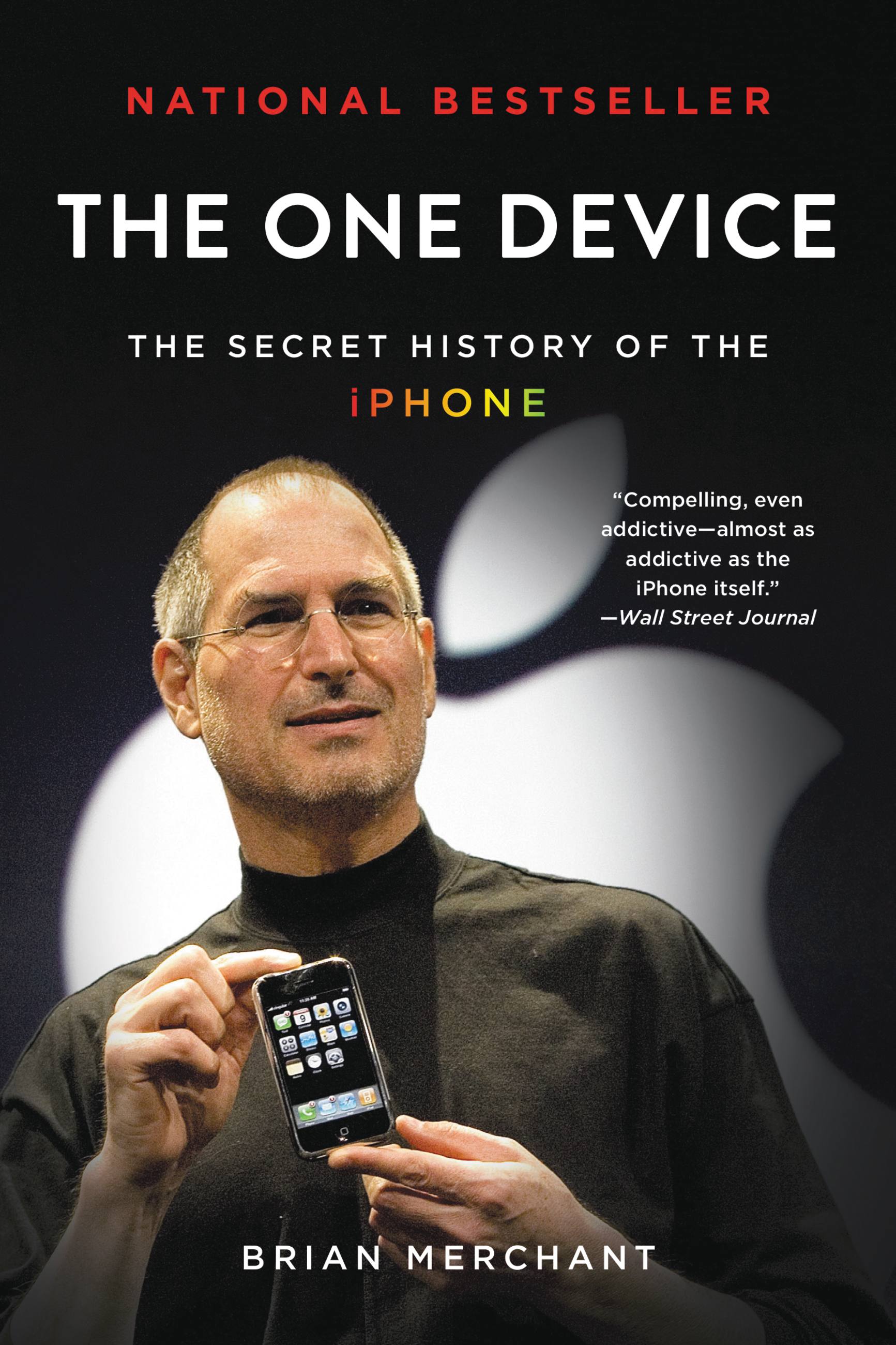

The One Device

The Secret History of the iPhone

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 20, 2017

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316546119

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 20, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The secret history of the invention that changed everything-and became the most profitable product in the world.

“The One Device is a tour de force, with a fast-paced edge and heaps of analytical insight.”-Ashlee Vance, New York Times bestselling author of Elon Musk

“A stunning book. You will never look at your iPhone the same way again.” -Dan Lyons, New York Times bestselling author of Disrupted

Odds are that as you read this, an iPhone is within reach. But before Steve Jobs introduced us to “the one device,” as he called it, a cell phone was merely what you used to make calls on the go.

How did the iPhone transform our world and turn Apple into the most valuable company ever? Veteran technology journalist Brian Merchant reveals the inside story you won’t hear from Cupertino-based on his exclusive interviews with the engineers, inventors, and developers who guided every stage of the iPhone’s creation.

This deep dive takes you from inside One Infinite Loop to 19th century France to WWII America, from the driest place on earth to a Kenyan pit of toxic e-waste, and even deep inside Shenzhen’s notorious “suicide factories.” It’s a firsthand look at how the cutting-edge tech that makes the world work-touch screens, motion trackers, and even AI-made their way into our pockets.

The One Device is a roadmap for design and engineering genius, an anthropology of the modern age, and an unprecedented view into one of the most secretive companies in history. This is the untold account, ten years in the making, of the device that changed everything.

“The One Device is a tour de force, with a fast-paced edge and heaps of analytical insight.”-Ashlee Vance, New York Times bestselling author of Elon Musk

“A stunning book. You will never look at your iPhone the same way again.” -Dan Lyons, New York Times bestselling author of Disrupted

Odds are that as you read this, an iPhone is within reach. But before Steve Jobs introduced us to “the one device,” as he called it, a cell phone was merely what you used to make calls on the go.

How did the iPhone transform our world and turn Apple into the most valuable company ever? Veteran technology journalist Brian Merchant reveals the inside story you won’t hear from Cupertino-based on his exclusive interviews with the engineers, inventors, and developers who guided every stage of the iPhone’s creation.

This deep dive takes you from inside One Infinite Loop to 19th century France to WWII America, from the driest place on earth to a Kenyan pit of toxic e-waste, and even deep inside Shenzhen’s notorious “suicide factories.” It’s a firsthand look at how the cutting-edge tech that makes the world work-touch screens, motion trackers, and even AI-made their way into our pockets.

The One Device is a roadmap for design and engineering genius, an anthropology of the modern age, and an unprecedented view into one of the most secretive companies in history. This is the untold account, ten years in the making, of the device that changed everything.

-

Shortlisted for the 2017 Financial Times Business Book of the Year Award and the 1-800-CEO-READS Award

One of the Best Business Books of 2017 - CNBC, Bloomberg, 1-800-CEO-Read, Financial Times, Marginal Revolution. Business Insider

A New York Times Book Review Editors' Choice -

"A remarkable tale... the story it tells is compelling, even addictive--almost as addictive as the iPhone itself."Wall Street Journal

-

"Like the best historians, Merchant... unpacks the history of the iPhone in a way that makes it seem both inevitable in its outline and surprising in its details."The Guardian

-

"Apple's culture of secrecy is no match for Brian Merchant in The One Device....Merchant tells a far richer story than I--having covered Apple for years as a journalist--have seen before... The iPhone masquerades as a thing not made by human hands. Merchant's book makes visible that human labor, and in the process dispels some of the fog and reality distortion that surround the iPhone."Lev Grossman, New York Times Book Review

-

"A fascinating story."Marketplace

-

"Merchant does the important work of excavating and compiling large numbers of details and anecdotes about the development of the iPhone, many of them previously unrecorded... Merchant tells a far richer story than the outside world has seen before."Minneapolis Star-Tribune

-

"Brian Merchant takes readers on an epic journey."Parade

-

"Brian Merchant gives us a rare look inside Apple, chronicling the development of the iPhone with details about everything from the selection of raw materials to the product's famous launch event."Gizmodo

-

"Fascinating... the author writes in the style of a fast-paced novel, with vivid details that help readers really understand how the iPhone was devised and launched."John Rampton, Entrepreneur

-

"A wild ride."San Francisco Chronicle

-

"An excellent book."Tyler Cowen, Marginal Revolution

-

"The One Device is a tour de force. Brian Merchant has dug into the iPhone like no other reporter before him, traveling the world to find the untold stories behind the device's creation and uncover the very real human costs that come with making the iPhone. Packed with vivid detail, the book carries the reader from one unexpected revelation to the next with a fast-paced edge and heaps of analytical insight."Ashlee Vance, New York Times bestselling author of Elon Musk

-

"This is a stunning book-a comprehensive, fascinating, and compulsively engaging account of how the most revolutionary product of our age was invented. Brian Merchant sets off on a journey around the globe, from design studios in California to mines in South America to factories in China, to tell the human stories-the ruined marriages, the lost lives-behind this iconic device. You will never look at your iPhone the same way again."Dan Lyons, New York Times bestselling author of Disrupted

-

"Brian Merchant has written a fascinating biography of the iPhone, the most important single product ever created. If you've looked at the glowing screen in your hand and wondered where the hell it came from, this book provides rich, unexpected, and unusually sophisticated answers."Alexis Madrigal, author of Powering the Dream

-

"Compressing decades of competitive invention and behind-the-screen intrigue, Brian Merchant looks deep into the black mirror of the iPhone to tell us the prehistory-and cultural future-of Apple's addictive device. This is the true science fiction of our time: how everyday experience was reinvented by a gadget."Geoff Manaugh, New York Times bestselling author of A Burglar's Guide to the City

-

"The One Device is a high-stakes adventure all thw ay down the global supply chain, from hush-hush design labs to dusty, desolate South American mines and sweeping Chinese factories the size of cities, passing through nearly every continent on Earth as it reveals the countless hidden lives that touch your iPhone before-and after-it passes through your hands. Think of it as the manual Apple would never give you: required reading for anyone who wants to know how their iPhone really works."Claire Evans, author and member of YACHT

-

"A thoughtful portrait of how a piece of reigning technology became ubiquitous in just a decade, for good and ill."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Riveting...a globe-trotting history that... lets us hear from some of the innovators who created the elements [of the iPhone]. A fascinating and surprising book."Library Journal

-

"Brian Merchant is a lovely writer... formidable... fascinating."The Times of London