Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

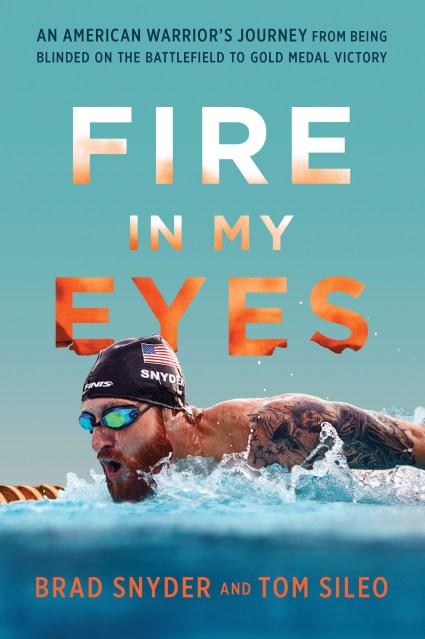

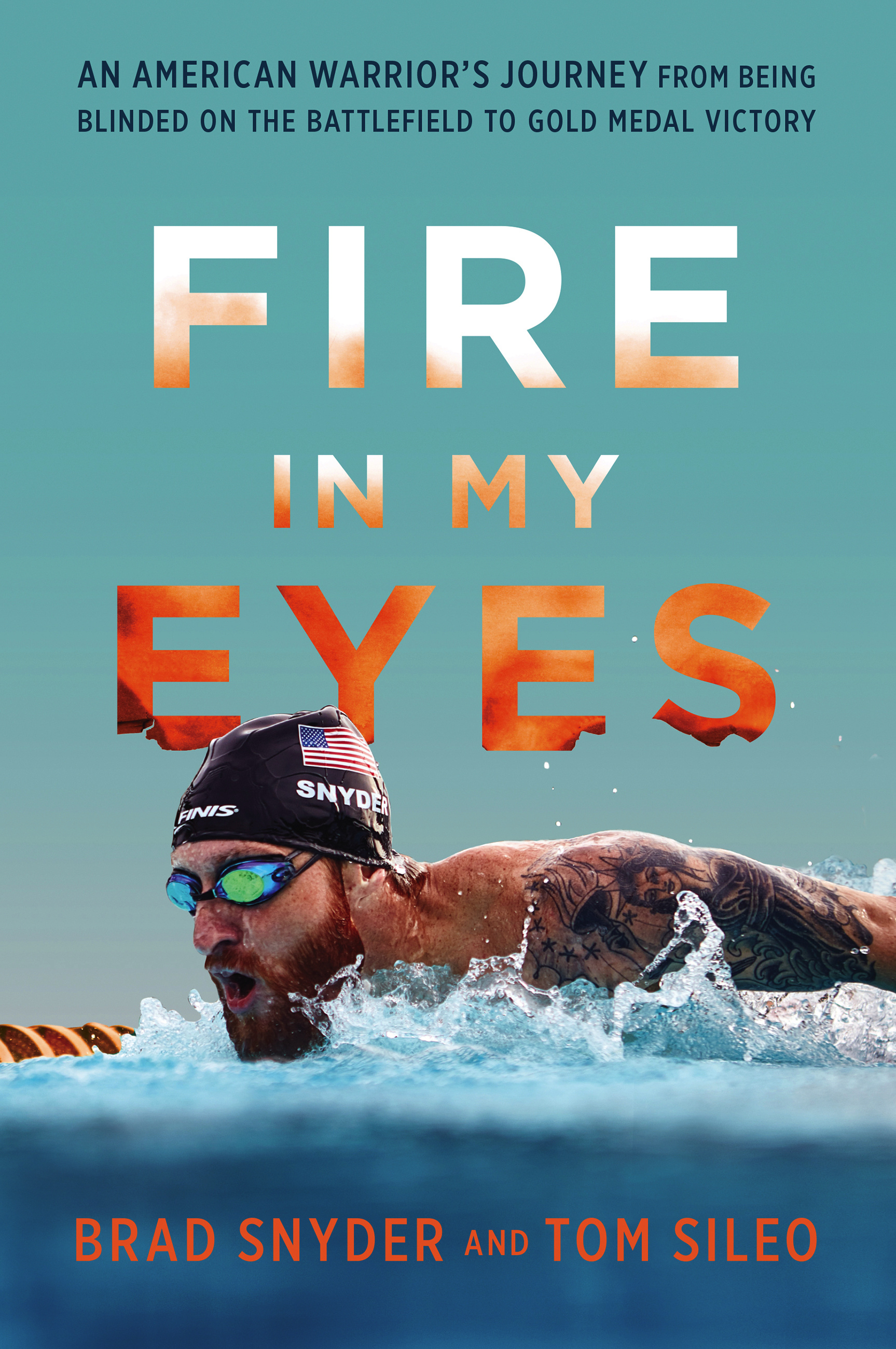

Fire in My Eyes

An American Warrior’s Journey from Being Blinded on the Battlefield to Gold Medal Victory

Contributors

By Brad Snyder

By Tom Sileo

Formats and Prices

Price

$36.00Price

$46.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 6, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“I am not going to let my blindness build a brick wall around me. I’d give my eyes one hundred times again to have the chance to do what I have done, and what I can still do.”-Brad Snyder speaking with First Lady Michelle Obama

On the night Osama bin Laden was killed, US Navy Lieutenant Brad Snyder was serving in Afghanistan as an Explosive Ordnance Disposal officer with SEAL Team Ten. When he learned of SEAL Team Six’s heroics across the Pakistani border, Brad was thankful. Still, he knew that his dangerous combat deployment would continue.

Less than five months later, Brad was engulfed by darkness after a massive blast caused by an enemy improvised explosive device. Suddenly Brad was blind, with vivid dreams serving as painful nightly reminders of his sacrifice.

Exactly one year after losing his sight, Brad heard thousands cheer as he stood on a podium in London. Incredibly, Brad had just won a gold medal in swimming at the 2012 Paralympic Games.

Fire in My Eyes is the astonishing true story of a wounded veteran who refused to give up. Lieutenant Brad Snyder did not let blindness build a wall around him-through tenacity and courage, he tore it down.

On the night Osama bin Laden was killed, US Navy Lieutenant Brad Snyder was serving in Afghanistan as an Explosive Ordnance Disposal officer with SEAL Team Ten. When he learned of SEAL Team Six’s heroics across the Pakistani border, Brad was thankful. Still, he knew that his dangerous combat deployment would continue.

Less than five months later, Brad was engulfed by darkness after a massive blast caused by an enemy improvised explosive device. Suddenly Brad was blind, with vivid dreams serving as painful nightly reminders of his sacrifice.

Exactly one year after losing his sight, Brad heard thousands cheer as he stood on a podium in London. Incredibly, Brad had just won a gold medal in swimming at the 2012 Paralympic Games.

Fire in My Eyes is the astonishing true story of a wounded veteran who refused to give up. Lieutenant Brad Snyder did not let blindness build a wall around him-through tenacity and courage, he tore it down.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 6, 2016

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306825149

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use